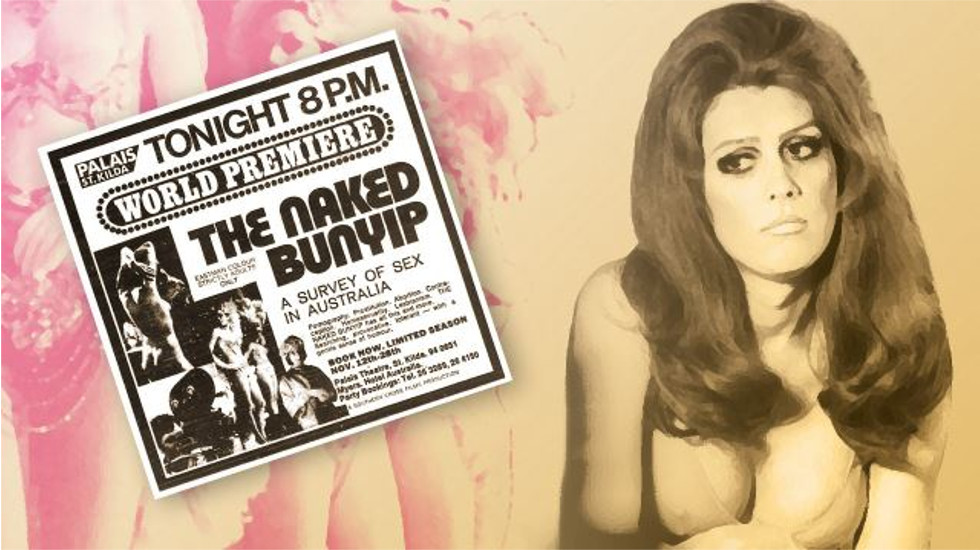

A poster for the groundbreaking 1970 Australian film “The Naked Bunyip”, directed by the late John B Murray.

Fifty years ago a comic documentary film, “The Naked Bunyip,” and a novel, “Portnoy’s Complaint,” challenged Australia’s conservative censorship system.

The director of “The Naked Bunyip,” John B Murray, died last month at the age of 88. Philip Roth, the American author of “Portnoy’s Complaint,” died in 2018.

But the story of his book’s misadventures in Australia was only recently published. “The Trials of Portnoy,” by Patrick Mullins, is an account of a bold campaign that helped free Australians of a controlling and patronising censorship regime.

1970 was quite a year for shaking things up. Carlton beat Collingwood in a VFL grand final that is still thought by some to be the most remarkable ever played. Melbourne’s West Gate Bridge collapsed, Germaine Greer‘s “The Female Eunuch” was published, and Australia’s first Aboriginal Legal Service was established in Redfern, NSW.

Clearly change was in the air, if not yet in the country’s institutions. And when John B Murray got together with executive producer Phillip Adams and financier Bob Jane (of motor racing and tyre fame), “The Naked Bunyip” was born.

Sex was its selling point, a subject that might, Murray and Adams hoped, persuade Australians to watch an Australian-made film, of which there had been all too few produced in the preceding 50 years.

Comedy, observational footage and candid interviews would be linked by a fictional character, a young market researcher (played by Graeme Blundell) surveying attitudes and sexual behaviours.

The filmmakers spoke with gay and straight men and women, prostitutes, strippers and cross dressers from Carlotta to Edna Everage.

They covered subjects from abortion to pornography to love, filmed life classes, childbirth and Russell Morris performing his hit song, “The Real Thing.” John Button (then a leading Labor lawyer) appeared in the film, as did physician Dr John Billings, women’s activist Beatrice Faust, journalist Keith Dunstan, actor Jacki Weaver and many others. It even featured an audio interview with English journalist and commentator, Malcolm Muggeridge.

But when the film was shown to Australia’s censors, they demanded cuts to material considered offensive.

Technically, Murray complied with their orders, but by substituting parodic drawings of a bunyip (by Peter Russell Clarke) for supposedly offending images, he highlighted their content and mocked the censors’ prudish, outdated views.

And when he screened an uncut version of his film to the media, he ensured maximum publicity for both the film and the anti-censorship cause.

Released in November 1970, “The Naked Bunyip” played to large audiences around the country for the next two years. It was a breakthrough film not only in terms of the fight against censorship, but also in the revival of the Australian film industry.

Meanwhile, Australia was in the midst of another anti-censorship battle, precipitated by Philip Roth’s novel, “Portnoy’s Complaint.”

His story of a lusting young Jewish man with a mother problem included accounts of the protagonist’s compulsive masturbation. The novel became an unlikely cause célèbre when its importation was banned by the Australian Government. Penguin Books responded by publishing a local edition, only to have copies seized by police in most states.

The 57-year-old manager of Perth’s “Pioneer Bookshop”, Joan Broomhall, was among a handful of Australian booksellers who defiantly sold the book, In September 1970, police arrived to confiscate her stocks of the novel, which was already a big seller. She was charged with selling an obscene publication.

After the first hearing in the case, Magistrate Malley of the Perth Court of Petty Sessions declared he would spend the coming weekend reading “Portnoy’s Complaint.”

Asked why he hadn’t done so earlier, he replied that reading the novel would have made him liable for prosecution too, for possessing an obscene book. He hadn’t considered requesting a copy from the police until they produced one of the seized volumes in court.

When the court resumed, writers, librarians, psychologists and schoolteachers testified to the literary merit of “Portnoy’s Complaint.” There were 17 expert witnesses in all.

Between Christmas and New Year, while the rest of the country digested its pudding and waited for the Fourth Test of an Ashes series to start (the third having been abandoned due to three days of continuous rain in Melbourne), Perth’s Court of Petty Sessions heard Phillip Roth’s work likened to that of Twain, Hemingway and Salinger – especially in its use of the vernacular. Prosecutor, Ian Viner, read obscene words to the court for almost an hour.

On January 19, 1971, Malley found “Portnoy’s Complaint” to be exempt from prohibition. Under West Australian state law, works of artistic, scientific or literary merit could not be banned.

Like “The Naked Bunyip,” “Portnoys Complaint” became a commercial success, more so than it might have done had there been no attempt to restrict its sale. With the profits, Perth’s “Pioneer Bookshop” was finally able to renovate its premises.

And after a series of similar trials around the country, censorship arrangements were renovated, too, and adult Australians were finally able to make their own decisions about what to read.

“The Trials of Portnoy” is published by Scribe and is available in book stores. “The Naked Bunyip” is available from Umbrella Films. Clips and a trailer can be viewed on YouTube.

Sharon Connolly is a writer and producer, a former CEO of Film Australia Ltd and author of a forthcoming book about women in Australian vaudeville. She is also the proud granddaughter of Joan Broomhall, once the manager of Perth’s Pioneer Bookshop.