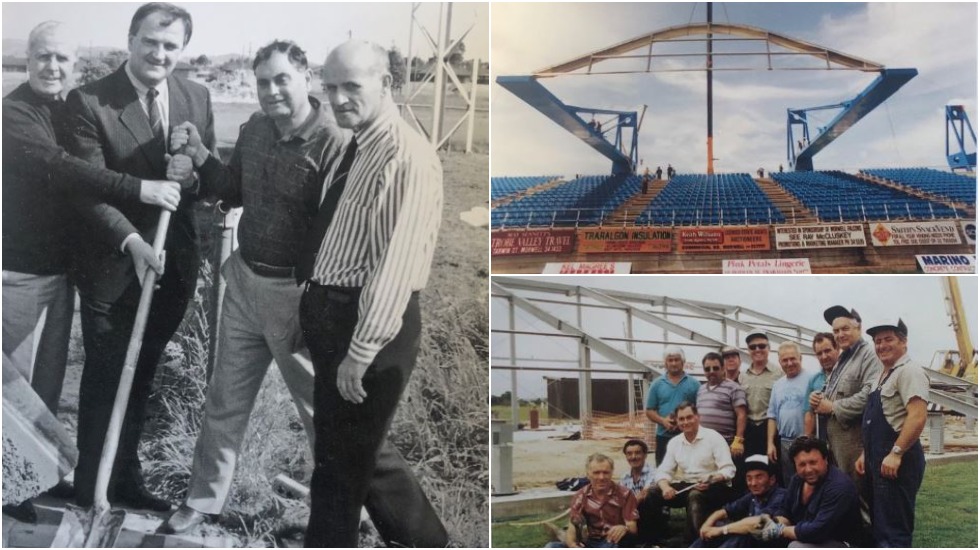

St George’s Barton Park, then (1987) and now, a derelict shell, and the long-gone Morwell Falcons and their once proud home.

“A-League hits new low in horrible scenes” screamed the headline on Tuesday morning, after just 990 people rocked up to watch Western United against Newcastle Jets the night before.

Yet while the figure is undoubtedly alarming, did anyone stop to consider one of the main reasons?

Western United is a new club, brought in primarily for its commitment to building a proper home. Once its 15,000 seater stadium in Wyndham is complete (and there is frustration that, as yet, not a single brick has been laid), football will have that rarest of commodities, a home of its own. AAMI Park – as fine as it is – is well out of Western’s catchment area, especially on a Monday night.

This is the story of many A-League clubs. Sydney FC is currently displaced from its natural home, the SFS (where it is only a tenant in any case), while Brisbane Roar trains on the Gold Coast, and plays in Redcliffe – thus bypassing Brisbane altogether.

Wellington Phoenix isn’t even playing in its own country thanks to COVID, while the Central Coast Mariners can’t get management rights to their home ground in Gosford – and reportedly have interest from potential buyers who’d like to uproot them completely and shift them to North Sydney. Western United? As well as AAMI Park, it has played at outsized ovals in Geelong, Ballarat, Melbourne (Whitten Oval) and Launceston.

The nomadic nature of these clubs is indicative of a competition that has too few of these “true” homes. A rough count of venues used for A-League matches since its inception in 2005 numbers 49 – for a 12-team competition.

Some clubs in the former National Soccer League performed better in this regard. Melbourne Knights, Sydney United, Marconi Stallions, South Melbourne – all still play out of what are proper homes of the game, many built by the hands of their own fans. Perth Glory and Adelaide United – two who made the crossover into the A-League – also have homes that are fit for purpose.

Yet many others have fallen into disrepair. Victims of the game’s internal politics, failing clubs, and the struggle the game continues to have in trying to penetrate governmental halls of power to unlock public money for refurbishments. Recurrent themes that echo down the generations.

Two of the best (or worst) examples of these “broken homes” lie 845 kilometres apart, linked only by the Monaro Highway and the fact that they once both hosted teams in the NSL.

The Latrobe City Stadium in Morwell (Victoria) and Barton Park in St George (NSW) are very visible symbols of football’s struggle for places it can call home.

Back in 1992, the Morwell Falcons entered the NSL as a replacement for Preston. For a while, the Falcons did well, reaching the finals in 1995. Under the presidency of local steel magnate Don di Fabrizio, the club’s supporters built an eye-catching new stand as the first part of the plan to redevelop their Falcons Park ground.

(Left): Officials lay the foundations for Morwell’s grandstand in 1992, taking shape thanks to much work by volunteers (bottom right).

But despite that early promise, the Falcons were done just nine years later – name changes to Gippsland Falcons and Eastern Pride failing to mask the financial issues which led to their demise in 2001.

The club’s successor – Falcons 2000, which was formed as the junior section in the dying days of Eastern Pride – still plays out of the venue, along with Gippsland FC, the junior team representing the region in the second tier NPL youth league.

But the stadium, and particularly the ornate stand, has fallen upon hard times – no longer compliant with modern safety standards, and characterised by broken seats, liberally spattered with bird shit. It hosts the odd W-League game for Melbourne Victory, which is how I first became aware of the ground and its history while calling a game there last year – but otherwise, it sits as a relic of the past.

In common with many other areas of the country, football remains the biggest sport in the LaTrobe region in terms of participation – but the sport has found it hard to attract the money needed to get the stadium (and particularly the stand) back to its former glory. The venue has passed into private ownership twice, and is now back in council hands. But serious investment remains elusive, aside of the construction of a synthetic playing pitch at the back of the stadium.

Current Falcons coach, Mark Cassar, takes up the story.

“Historically, this is one of the strongest areas in Victoria – the only region that was able to field an NSL club,” he says.

“But there seems to be a huge inequality between funds allocated to other sporting codes and ours. When Hazelwood Power Station closed here a few years ago, there was a huge amount of money put aside by government for sporting development and infrastructure.

“In Traralgon, there’s a big new aquatic centre, a basketball centre, and there were other sporting codes who got a fair chunk of the cash – in total around $80-$100million. The only major project that seemed to come out of that for us was the synthetic pitch. We got a very small piece of that funding.”

There is a master plan to revive the Latrobe City Stadium into a state-of-the-art, centre of excellence for football, but it’s been slow progress – as Graham Middlemiss from LaTrobe City Council admits.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

“The council is determined to complete that work, but it will take some time,” he says. “The stand is about stage three of our plan. The first work is to the changing rooms underneath, and some of that has been done, although there were issues with the design.

“We haven’t forgotten football, we are just trying to get funding, which is needed for a very ambitious project to bring it back to where it was. Our proposals were just being developed when the state government was making their funding decisions. They should have got a higher level of consideration, no doubt – but football was overlooked in favour of shovel-ready projects.”

Local MP Russell Northe, however, is advocating more urgency, particularly with the FIFA Women’s World Cup coming to these shores in 2023, offering an opportunity for the region to host one of the competing nations as a training venue.

“Unfortunately, very little of the overall master plan has been actioned in recent years, which is highly frustrating for the football community, and it’s a missed opportunity,” he says.

“My view is that we need to try and leverage support from Football Victoria and the state government along with local government and council to develop this site as soon as practical. The facilities desperately need modernising and the only way to make that happen is partnerships.”

Yet for all the frustration at the apathy outside the game, Falcons vice-president Anthony Cefala says internal politics is just as big a hindrance.

“It’s about uniting the community, having an organised plan. We have 13 clubs overall in the region in the LaTrobe Valley Soccer League. But clubs look after their own interests,” he says.

“There isn’t an over-arching group of people that are willing to look at the bigger picture. If we could have a side playing at NPL level or state level – a united team to represent the area (which is what the Falcons were), that would be a start.”

This is a theme echoed in the St George area of Sydney, where the famous Barton Park ground – home to the likes of Johnny Warren back in the 1970s – lies almost derelict, as it too waits for a master plan to swing into action.

In its NSL days as the home of St George Budapest, a smart grandstand was built in 1979 to boost the capacity of the venue to around 12,000. Four years later, the club won its first and only NSL championship under Frank Arok. It hosted the NSL grand final a year later, and Socceroos internationals too. Yet by 1991, the club was gone from the top flight – never to return. The ground suffered accordingly.

By 2008, St George’s Barton Park was closed off to the public, its grandstand deemed unsafe even before it lost its roof.

By 2008, the stand was deemed unsafe, and today it is a shell – closed off to the public, shorn of its roof, and full of graffiti. There have been various plans to restore the ground to its former glory – and Football Australia says it remains a site under consideration for a new national home of the game. It still hosts junior matches, but the local landscape is typically fractured.

In the St George area alone, there is St George Saints (the successor to Budapest), St George City FC (both clubs play in NPL2), Rockdale Ilinden (NPL1) and Hurstville FC (NPL4).

Craig Kiely is the chief executive of the St George FA, the local association overseeing the sport in the area.

“If we spoke with one voice it would be easier to get better facilities,” he says. “If there was one St George club, it would be a powerhouse. There is so much history in the area. Supported by the association, it would help to unlock those opportunities.

“If someone from the AFL goes into a council meeting, they are talking as the AFL. We go in and I’m speaking as St George FA – then there’s a state body, a federal body – we’re all different, all the way up. If we go for a grant, there’s our letter, and there’s at least two others from the different layers. It’s symbolic of the challenges we face.”

“The fact that the stadium has been left to deteriorate is a real shame. There’s so much land, so much history. It’s right next to the airport – it is the perfect fit for the home of football. There should be a museum there, world class facilities. It’s embarrassing, and really sad it has got to that state.”

And so, football’s search for proper homes continues. The biggest losers in their absence? The supporters, who struggle to identify with venues that aren’t necessarily fit for purpose, leading to crowd numbers such as the one we saw on Monday night.

Without proper homes and clubs that stand the test of time, some of those fans simply drop away. One such example is Steve Bricknell, who gets the final word. Steve was a passionate Falcons fan, but now feels utterly disconnected from the game.

“It’s really sad. I grew up there,” he says. “There was a group of about 15 of us – we’d change ends at half time. We did that for 10 years, and we still catch up today. But not a lot of us follow the game anymore.

“That was our club, and it died. Some go to Victory games, but the Falcons were a part of our childhood. We went through a lot together. I haven’t been to a live game in years.”

Love yo have a chat you Simon as I am now chairman of StGeorge FC

I grew up in Morwell, 60’s through to the early 80’s, and the round ball was everywhere – thanks to the post-war immigrants who came to the Valley and made it Victoria’s industrial heartland. And a pretty diverse heartland at that.

I played a few junior seasons with Rangers, a very Scot’s/English flavoured club. Our competitors were clubs such as Pegasus, Fortuna, and yes, Falcons.

I don’t think anyone out side that club could appreciate just how high they would fly, but then Falcons was always a club that seemed bonded by a real sense of community. To that end, perhaps their demise somehow mirrored the social fracturing of the town itself, brought about by the savage cuts and closures orchestrated from afar by Spring Street politicians and faceless bureaucrats.

Still, perhaps the club (in one form or another) will rise again – same as the town will, and the region too.