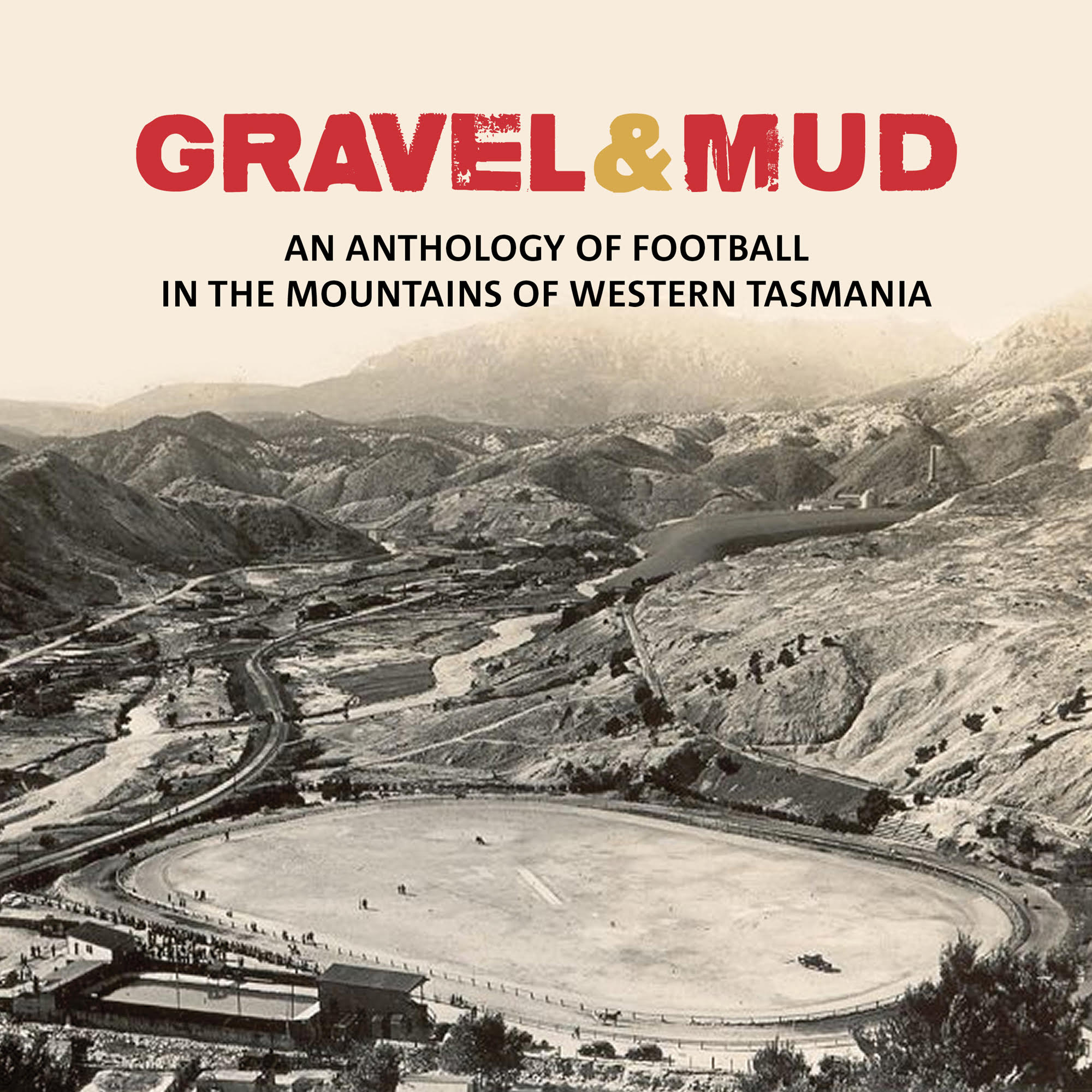

Clouds, rain and footy on gravel. A familiar sight when it comes to football in Queenstown, on the west coast of Tasmania.

I met John Carswell, the man behind this book, playing footy for the Tasmanian University Football Club in the 1970s. John was that intriguing paradox – a gentle man who’s a tough footballer. Big-chested with wild frizzy hair and beard, and a nose that’s been at an angle to his face for as long as I’ve known him. He was instantly likable, a humble man who constantly backtracks in his speech to let other speakers through, but on the football field no-one intimidated him. That made him a welcome addition to our club as we played some teams who were very intimidating and didn’t like us, this being the era of student protests.

In 1983, the West Coast of Tasmania was split asunder by the battle to stop the damming of one of Tasmania’s last wild rivers, the Franklin, by the State Government. Queenstown was the stronghold of the pro-development forces. John Carswell sided with the protestors. During the 1983 season, playing with the Queenstown Blues, he heard chants of “Get the Greenie bastard”. In the grand final, he was king-hit from behind. He woke from unconsciousness with his head in a blood-stained puddle, played on and was named by the Burnie Advocate as the winning Queenstown team’s best player.

John’s home contains no fewer than 20 art works to do with the West Coast. Each painting launches him on a softly-spoken monologue – where the place is, how you get there, how artists like William Piguenit got there in the 19th century. He has also climbed mountains all over the world, including the Antarctic. The highest peak he has climbed, Aconcagua (22837 feet), is in the Andes. When I ask him the first thing that comes to mind when he thinks of the West Coast of Tasmania, he says mountains. He climbed his first, with his father, when he was nine.

The book John cajoled into being, “Gravel and Mud”, is a labour of love. It is part celebration, part elegy, for a game that is in sad decline in the island state, which should be a matter of concern to football lovers everywhere. Over the last 100 years, there have been eight different football associations on the West Coast of Tasmania. Today there are none. In the same period, the West Coast has had at least 99 different football clubs. Today it has two.

Tony Newport (left) and John Carswell, who wrote the new book chronicling football on the west coast of Tasmania, “Gravel and Mud”.

The first game of football on the West Coast was played at Strahan in 1888. I can tell you the method of scoring, exactly where in Strahan it was played and the weather on the day. The reason I can tell you all that is because John’s older brother Chris told me. I went to school with Chris Carswell and we were later at university together in Hobart where he had a reputation as a political activist committed to reforming – some said overthrowing – the Tasmanian Labor Party which then ruled the island with Soviet-like certainty. In later life, working as a statistician for the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Chris became interested in what he calls “the detail of things”. What Chris brought to this book was knowledgeable perspectives. Lots of them.

I qualified for the book because my schoolteacher father was transferred to Rosebery, a mining town on the West Coast, when I was eight. Our first year, there was more than 100 inches (250 centimetres) of rain. I was taken to a game of local footy. The ground looked like it was covered in brown gravy. It was mud and, within minutes of the start, the players were indistinguishable from one another.

The sections of the book dealing with mud were written by Tony Newport. He has worked at everything from being an underground miner to being a street busker. He plays the autoharp and sings songs that celebrate the Rosebery of his childhood, the Green Line bus that left from outside Winskill’s newsagency, the small miners’ houses made of tin. Tony played in three premierships with Rosebery Football Club. Tony thinks before he speaks, and uses only as many words as are necessary to convey his meaning. These qualities, plus an understated lyricism, distinguish in his writing.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

In 2007, I was inducted into the Tasmanian AFL Hall of Fame for my football writings. To my delight, I was inducted along with one of Tasmanian football’s icons – Queenstown’s gravel oval. Rosebery teams could win all year in the mud and lose the grand final because it was played “on the gravel”. I did a tour of the Queenstown oval with John and Tony, both of whom had played grand finals there, walking the white desert surface, seeing where each of the three famous old Queenstown clubs – Lyell, City and Smelters, now all gone – had their rooms. We stood in Paulsen’s pocket, so-named after tent boxing impresario Harry Paulsen, who toured Tasmanian shows in the 1960s. This was where the fights happened.

With John and Tony and Ralph Burns, a Gormanston premiership player from the 1960s, I went to the Gormanston oval. Gormy, as they were known, lost the right to host home games after their supporters burnt down the visiting team’s changerooms in 1937. They had a special reputation in Tasmanian football as being one of the roughest, toughest teams in the island. They were the Mountain Men.

Queenstown is ringed by mountains – on the top of one is Gormanston. The mountain you climb to get to Gormanston is pink and bare and rocky. In places, it is clad in new green clothing as the bush comes back, the smelter with its noxious fumes having closed. Gormanston has all but gone. It had a population of more than 2000. Now it’s half-a-dozen houses with deserted streets and the bush poking its rough green head through everywhere. It’s a bare bony place with bush that only grows to shoulder height because of the wind. Further mountains, dull in colour, close-cropped by the wind, hover above and around it.

Chris Carswell’s mother Elsie was born in Gormanston and lived there until the age of 23. (The Carswell brothers are first cousins of Brisbane Lions coach Chris Fagan, who has written a terrific foreword for the book). Chris and John’s Uncle Ack lived alone in a small shack beside the Gormy footy ground. Uncle Ack’s hut has gone as have the row of houses that looked down on the ground in its playing days. It’s the memory of a football ground now. One goalsquare is a big pond with rushes sprouting through the brown water, but the shape of the ground is still discernible as is the white gravel playing surface.

It’s one of many abandoned football grounds around Tasmania. Clearly, the AFL cannot be blamed for the vagaries of the mining industry, but for too long the AFL’s attitude to the island has been imperial. Tasmania was ruled from Melbourne by an organization that succumbed to the lethal delusion that it was the game and valued Tasmania only for the recruits it supplied and the television audience it guaranteed for its “product”. The time has come for the AFL to look at Tasmanian football from the bottom up, not the top down, to talk to the volunteers and local clubs who actually keep the game alive against increasing odds. And don’t pass North Melbourne off on us. It won’t work. The issue is Tasmanian pride. Always has been.

The day I went to Gormanston’s footy ground, I asked Ralph Burns if he remembered the Gormy club song. He started: “We Are, We Are, We Are!” He sang it proud like he wanted the mountains to hear. He sang it again: “We Are, We Are, We Are!”, then said, “I don’t remember the rest”. He didn’t have to. He’d spoken for Tassie football. We Are We Are We Are. But if the AFL gets the next step wrong, we may not be.

I just want to say what a wonderful article. I remember my own late father, working in Zeeshan in the 50’s, telling me about playing on gravel. Thanks.

Thanks again Martin, another great article. A good man, Carsy. Had a couple of very enjoyable years teaching in Queenstown and playing under former Geelong player Hugh Strahan. It is a town with a rich history and colourful stories …the best ones may never be shared because of censorship laws I suspect.