Dusty Baker celebrates after his Houston Atros won baseball’s World Series against the Philadelphia Phillies. Photo AP.

It was Saturday night in Central California, about 30 minutes before I was about to cover the Collingwood-Western Bulldogs AFLW elimination final for Footyology, and I was feeling conflicted.

As one eye scanned my pre-match notes, the other was watching game six of baseball’s World Series between the Houston Astros and Philadelphia Phillies.

The Astros are mostly the same bunch of players who defeated their World Series opponent the Los Angeles Dodgers five years ago, but were then busted for scandalously decoding, then stealing, signs their coaches were relaying to their players. Not exactly the type of thing that inspires a neutral like me to barrack for them.

Yet as the Astros recorded the game’s final out and began their on-field celebration, I smiled and felt a warm sense of happiness.

Don’t get me wrong — I wasn’t cheering the success of a team for cheating years ago, as the Astros did, then escaping with an MLB virtual wrist slap.

I was quietly celebrating the accomplishment of Astros’ manager (senior coach) Dusty Baker, MLB’s longest-tenured African American in that position, who in his 25-year career has led five different clubs and had won two league championships but never the grand prize that eluded him — a World Series championship.

The Astros hired Baker in 2020 to restore to their organization credibility, class, and character.

In a press conference in the lead-up to the showdown with the underdog Phillies, Baker demonstrated all three traits by bluntly addressing MLB’s most uncomfortable truth, which has haunted the league for the last three decades: a shocking decline of African American players.

It was a fact again laid bare by this World Series. For the first time since 1950 — three years after Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby broke the league’s colour barrier — not a single African American featured for either side.

“I don’t think that that’s something that baseball should really be proud of,” said Baker, one of 15 African American managers in MLB’s 153-year history, and just the third to lead a team to a World Series championship. “It looks bad.”

The percentage of African Americans on MLB lists at the start of this season was, according to a Newsweek magazine report, seven per cent — down from about 20 per cent in the early 1990s.

If you’re scoring at home, African Americans make up about 12.5 per cent of the total US population, according to the 2020 US Census.

To be fair, myriad factors account for the low MLB numbers, and it is not entirely the league’s fault. To its credit, MLB has over the years instituted programs in largely African American urban communities to recruit potential young players.

But other sports, like gridiron and basketball, are far more accessible and affordable to and popular with African American youth.

The NBA and NFL also have far exceeded MLB’s efforts to market their league to young people in general. Baseball long ago lost its grip as the US’s dominant sport. In this fast-moving, high-stimuli society, many American youth see baseball as “slow” and “boring” when compared to other sports.

Baseball also requires players to have extraordinary patience and perseverance — batters, for example, fail at three or four times the rate they succeed and get reward for effort.

Basketball and gridiron often deliver instant gratification, with university players being drafted to and joining clubs in the same year and earning big money, while the overwhelming majority of MLB-drafted baseballers must spend an average of two to four years refining their skills, playing for their respective clubs’ lower level, minor league affiliate teams.

And while African American MLB representation has steadily decreased, the numbers of deserving Latin American players of African heritage, whether from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela or Cuba, has increased to the point where Latin American-born players make up nearly 30 per cent of MLB lists.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Still, that seven per cent is downright embarrassing, especially considering the special relationship African Americans have had with baseball dating back to the 19th century.

In 1867, two years after our emancipation from slavery, two sons of iconic abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass — Fred Jr. and Charles – played on rival Washington D.C. teams.

Other African American baseballers played with and against white players, including a player named Moses Fleetwood Walker, who debuted in 1884 for a major league Toledo, Ohio-based team in a competition called the American Association.

Just three years later, though, as baseball gained popularity and became known as “America’s national pastime,” major league club owners made their infamous “gentleman’s agreement,” barring black players.

Instead of despairing from that blatant racism, African American business entrepreneurs and players in 1910 formed their own national, professional baseball competition, the Negro Leagues.

And in 1947, with African Americans suffering under institutionally racist Jim Crow segregation laws, the catalyst for the decades-long civil rights movement — which legally ended those laws — happened on Major League Baseball diamonds, former Negro Leaguers Robinson and Doby debuting for Brooklyn and Cleveland respectively, after those teams’ socially progressive-minded white general managers boldly defied the “gentlemen’s agreement.”

MLB’s integration predates such other watershed civil rights actions as the integration of the US Armed Forces, the Supreme Court decision outlawing public school segregation, and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. leading a bus system boycott that eventually led to the desegregation of public transportation, and eventually all US public spaces.

Baker, now 73, grew up in Southern California and debuted in 1968 as a 19-year-old with the Atlanta Braves, four years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act,

One of Baker’s older teammates and mentors was the legendary Henry Aaron, who briefly played in the Negro Leagues in the 1950s and shared with him encounters he had with Robinson.

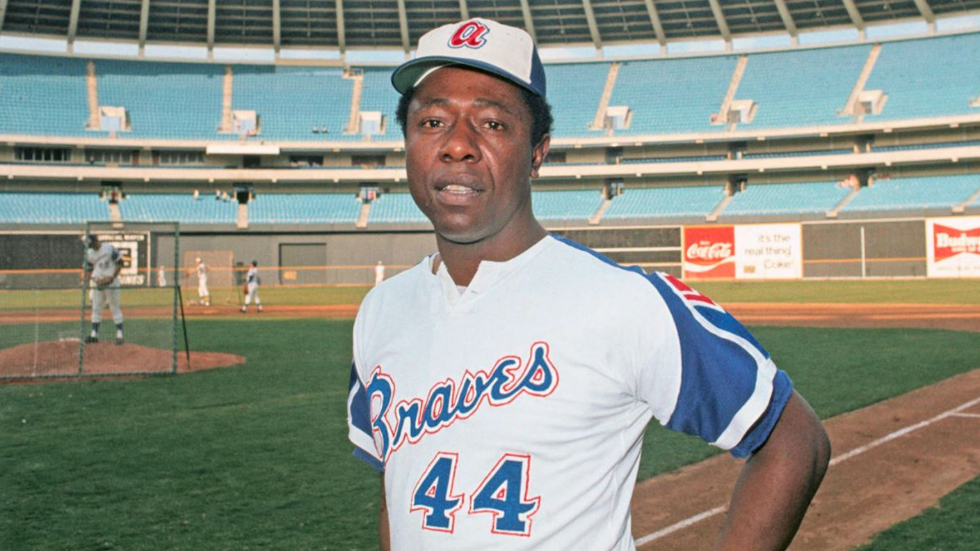

Baseball legend Hank Aaron, pictured during his stint with the Atlanta Braves.

In the early 1970s, as Aaron pursued and eventually broke Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record, Baker witnessed Aaron copping the same vile racism — including death threats — Robinson and Doby had, when they started their Major League careers.

A few years before Aaron’s record-smashing 1974 home run, I first crossed paths with Baker, albeit from a distance.

I was in the stands at New York’s Shea Stadium, where my father had taken me to see my first MLB game — our Mets against Baker’s Braves. Just as Baker’s dad taught him to revere the game, my dad did the same with me, raising me on it. But sadly, it seems that fewer and fewer African American dads over the last few decades have done this with their sons, opting to teach them other sports.

I’ve seen this play out over the last five years at independent high schools where in addition to teaching humanities courses, I double as an assistant baseball coach. In that time, I’ve coached just two African American players.

When I start a new coaching season, I share with the players that my deep love for baseball lies not only in its beauty, not only because since my birth it continues to epitomise the loving relationship my father and I share, and not only because of the part it played in my courtship of my wife.

It’s also because of baseball’s historic role in testing individual character and directly and indirectly bringing about social equity and justice.

This past July brought a glimmer of hope for increased African American MLB representation. For the first time in MLB history, four of the first five players selected in the league’s annual amateur draft were African American.

All four also played in the MLB-created DREAM Series, which specifically targets African American talent, and some MLB teams have recruited other African American players to baseball academies they’ve created.

At that same pre-World Series press conference in which Baker lamented the current lack of African Americans in MLB, he praised what might be a righteous revival.

“There is help on the way,” Baker said. “You can tell by the number of African American No. 1 draft choices. The academies are producing players. So hopefully in the near future, we won’t have to talk about this anymore or even be in this situation.”