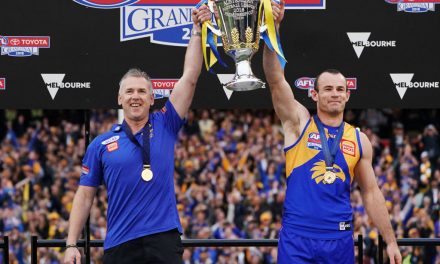

AFL chief executive Gillon McLachlan and the now former Collingwood president Eddie McGuire. Photo: AFL MEDIA

Barack Obama writes in the preface of his first presidential memoir, based on his rise and much of his eight-year tenure as US President, that he did not achieve all he planned or hoped to accomplish during his time at the White House.

But the 44th President of the United States adds in “A Promised Land” that he left his country in a “better shape” than he found it. This is the ideal ambition of every leader.

And then Obama’s legacy was challenged and attacked by his now deposed successor, Donald Trump.

In the past year, too, one like no other, the perceptions and fortunes of many other presidents of a football variety, in particular Eddie McGuire at Collingwood and Rob Chapman at Adelaide, have changed … and the transformation of their legacies has little to do with the rampant threat posed by COVID.

But the pandemic certainly has changed how AFL chief executive Gillon McLachlan is to be remembered.

His legacy is to be far more than record television rights and the successful launch of AFLW, the national women’s league he fast-tracked to start in 2017 rather than the planned 2020 season. Or will blunting that sharpening thorn known as Tasmanian football also significantly define the McLachlan era or be a task left to his eventual successor?

McLachlan, who succeeded Andrew Demetriou in 2014, is considered by some to be in extra time while he starts his seventh AFL season in the chief executive’s chair at Docklands in Melbourne. He has achieved far more than was first imagined within his destiny in a demanding job that has more critics than praise.

It is worth remembering this time last year – after there had been an eager guessing game as to which AFL club chief executive (such as Xavier Campbell at Essendon or Brendon Gale at Richmond, in particular Gale) would succeed McLachlan – the AFL boss endured a strange interview on national subscription television.

It is one of those moments that will not fade from the memory. It also is a reminder of how many in football seek to run ahead of the script – in a landscape where many seek to be “first with the news”.

On Fox Footy’s “AFL360”, co-host Mark Robinson – accepting the intriguing notion that 2020 was to have been McLachlan’s final year at AFL House – struggled to ask if the still unfolding and deepening consequences of the COVID pandemic changed his plans (real or otherwise).

“Would you,” asked Robinson of McLachlan, “have to re-think your future at the AFL ….”

Here was the assumption that McLachlan already had a farewell speech written for the end of 2020 and was grooming a successor – a thought held by more than just Robinson, for one reason or another.

“Bearing in mind,” added Robinson, “that the consequences of this coronavirus could be felt for many a year?”

After an uneasy pause – and not one created by communicating on Zoom – McLachlan replied: “I don’t know quite what the question is, but in terms of everyone sharing the financial pain, absolutely.”

Robinson was not letting go of the prospective headline: “McLachlan delays exit.” “The second question is,” he continued, “does this coronavirus have any impact on your future with the AFL?”

McLachlan replied: “In what sense Robbo, I mean my job right now is to get us all through.”

And McLachlan and his executive team at AFL House certainly did that with a fully completed AFL premiership season that carries no demeaning asterisk – and ended with a significant financial drain that worked out at $100 million rather than the first projected $600 million.

No-one is any longer expecting McLachlan to clear his desk at Docklands anytime soon, either. The same has not been the case for others – including club leaders who a year ago seemed rock solid in their hold on power, both at their club and in the game.

Despite the need for consolidation and stability to meet unprecedented challenges during the COVID pandemic, the off-season has marked the departure of several key and prominent figures at AFL clubs. Some were expected; some were advanced from the original exit dates and one, at Geelong, defined good governance at a model club.

But what of the legacies of Collingwood president McGuire, Western Bulldogs leader Peter Gordon, Geelong counterpart Colin Carter, Adelaide duo Chapman and chief executive Andrew Fagan, and Port Adelaide chief executive Keith Thomas?

Some suffer from hubris; others are enhanced by achievement.

McGuire certainly has a complicated legacy. The man who stepped up at the end of 1998 to advance the Collingwood Football Club from Melbourne suburbia to national relevance while the VFL became the AFL cannot have all of his grand achievements tarnished by his messy exit.

McGuire successfully led Collingwood – in the image of a modern-day Moses – from antiquated Victoria Park to the growth field of the MCG. He replaced the blue-collar image of Hard Yakka with the Collins Street style of Gucci. He made Collingwood a powerful brand – and then became more concerned with that brand than the true needs of club under the heat of a self-made crisis.

McGuire charmed corporate sponsors to dramatically change Collingwood’s financial power; but ultimately, he scared those backers being questioned on their support of a club accused of systemic racism.

“I have become a lightning rod for vitriol; (this) made it hard for the club to move forward with its plans … our sponsors are also under pressure,” admitted McGuire during his recent farewell at Collingwood.

Amazing is it not that such a consummate media performer would become undermined by his words at two press conferences. Or that a club leader who developed the perception of being more powerful than AFL commissioners became blinded on the political plays in his own domain at Collingwood.

Hubris indeed. And another example of the problem posed when one man seems bigger than his football club.

Before the systemic racism issue at Collingwood became McGuire’s undoing, Footyology posed to former Sydney chairman Richard Colless – a long-time sparring partner of McGuire in the AFL circus – the legacy question as McGuire planned his farewell tour through the 2021 season.

Colless told Footology last month: “You don’t last for that long in this environment unless you are pretty bloody good.” He also acknowledged McGuire’s commitment – and passion. “Eddie has that in abundance. Some might say it is a negative (when it blinds McGuire to the Collingwood agenda). But if you don’t have it, you can’t do this job.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

“Eddie is a genuine football person. I have warmed to Eddie for his passion towards the game as a whole. He is not there for reasons of money or personal advancement. Yes, he can drive you mad when he goes on about Collingwood. But you cannot deny his passion also extends to the broader needs of the game.”

How much of more than two decades of strong achievement – and advancing Collingwood from rock bottom in 1999 – is lost by an inglorious exit?

At Adelaide, Chapman began to appear a replica of McGuire, particularly with his public profile defined by his power at the Adelaide Football Club rather than through his other roles around town, such as chairman of the Adelaide Airport board. It is not hard to imagine which directorship drew more attention at dinner parties.

Despite insisting he wanted to leave the chairmanship at Adelaide, Chapman had no obvious successor – not even Brownlow medallist Mark Ricciuto – emerging on his board.

And an extension of his tenure seemed likely last year while many highly fancied contenders declined to step into the volunteer role that would command as much as 70 hours a week while Adelaide undergoes strategic change on and off the field. Then the old guard at Adelaide leaned on 75-year-old former State Premier John Olsen to end the Chapman era.

What is Chapman’s legacy at a club that has had such extreme chapters – the Kurt Tippett salary cap scandal, the Phil Walsh tragedy, the 2017 grand final appearance, the unprecedented fall to the AFL wooden spoon last season and AFLW success – during his leadership? Are the Crows better than when Chapman succeeded Bill Sanders as chairman in 2009?

The answer might have been different had vice-chairman Bob Foord lived to take charge after the 2017 AFL grand final, allowing Chapman to exit before the Crows spent the past three years in freefall to the wooden spoon – and serious questions on the state of a once solid and admired football team.

Fagan arrived late in 2014 – replacing Steven Trigg as chief executive – with two hurdles to immediately overcome. He was not only an “outsider” from Sydney via Canberra – he also was new to Australian football, having worked in rugby, as noted in his early interviews in which he would say “pitch” rather than “oval”.

Fagan set up his own legacy test by declaring his goal: “The vision should be (to make the Crows) the most respected and successful (team) in the country. That is my history … deliver the best football program because that is what you can control. Put the right people in the right seats – and get the right system in place. That is the focus for me – give the Adelaide Crows the best football program in the AFL.”

Adelaide’s best achievements in Fagan’s time were the work of people – in particular David Noble and Phil Harper – appointed before he came from the Canberra Brumbies.

One long-serving Crows leader said it best: “Andrew Fagan made the club commercially stronger – and culturally weaker.” Club legend Andrew McLeod’s public remarks about the cultural change at Adelaide reaffirmed the Crows were on a troubled path as a club – not just an underperforming team.

Fagan built an empire to his vision, not necessarily to the needs or wishes of his club’s members or fans. That vision is now to fade. Fagan’s legacy at Adelaide might only amount to a slogan: “We Fly As One”. He certainly is challenged to say he met the late Phil Walsh’s wish to build an “authentic football club” at Adelaide.

At Port Adelaide, Thomas’ legacy is the continued existence of the football club he entered as an “outsider” – or as was said at the time, “an SANFL plant” – during those dark and uncertain moments at Alberton in 2010 and 2011.

Thomas left Alberton at the end of last season with Port Adelaide still in the AFL – and as Port Adelaide. He had arrived in 2011 when the club was unable to secure a multi-national company as a corporate sponsor. Today, Port Adelaide has three. He took his seat when the team played before covered terraces at Football Park and led to packed houses at Adelaide Oval … and to Shanghai, China.

Like Barack Obama, Thomas cleared his desk with Port Adelaide in better shape. Much better shape. And like Obama, Thomas thought he could do more – hence his offer to stay on for an extra year to ensure Port Adelaide had stability amid the challenges posed during and after COVID. Club president David Koch preferred to start a new agenda with a new chief executive, Matthew Richardson.

Thomas’ legacy is a stark contrast to the doomsday destiny that came before him.

Carter leaves Geelong with a record befitting a man with a grand legacy from his stint at the game’s highest forum, the AFL Commission, and in corporate business. And there is not the slightest hint of hubris with his humble leadership.

Carter’s decade as Geelong president is marked with achievement on and off the field – the 2011 AFL premiership – while maintaining the most-competitive national league with a 69 per cent winning rate and appearances in nine of 10 finals series; a sound financial platform that held up to the threats posed by the COVID pandemic; and advancing the redevelopment of Geelong’s traditional home at Kardinia Park.

Carter certainly leaves Geelong with many noting he could have easily stayed. It is another ideal legacy. And he is still fighting for the AFL to recognise all of Australian football history rather than solely the chapters written after the VFL formed in 1897.

Gordon has the most extraordinary legacy. From his first stint as Footscray president from 1989-1996, he saved the club from a merger with Fitzroy when AFL national expansion was coupled with the belief there needed to fewer Melbourne-based teams.

Gordon’s second stint from 2012, when Footscray was firmly the Western Bulldogs, delivered the 2016 AFL premiership to end a 62-year drought. Survival – and success.

But the understated part of Gordon’s tenure as president of a less fashionable AFL club in a crowded market is in how the lawyer stood tall and commanded recognition from the big boys – such as McGuire and Jeff Kennett. He made sure they understood the collective approach in a league that cannot afford to create a chasm in the divide between the “haves” and “have nots”.

Very few get to write their epitaphs or decide how their legacies are measured and valued. When acclaimed English actor Paul Eddington, who portrayed the very image-conscious Jim Hacker in “Yes Minister” and “Yes, Prime Minister”, sat for his last television interview, he was asked how he wanted to be remembered. “He did very little harm,” he replied.

But who among those who are leaving the game today did much good for Australian football – and who can move on with their legacy standing the test of time and meeting that ultimate challenge of leaving a club or team better than how they found it?