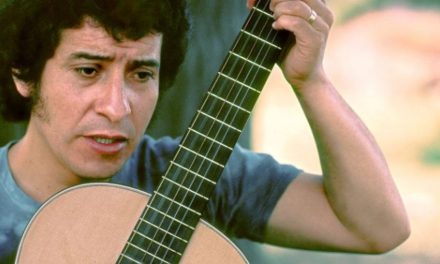

Martin Flanagan and his brother Tim carrying Mum and her wheelchair at a family wedding.

You would have seen the paddocks edging the Launceston CBD from your room, Mum, cows in them, heads buried in the grass. You might also have seen the rough blue line of Mount Arthur to the east. The mountain’s still there, Mum, so are the cows, but the Queen Victoria hospital’s not a hospital any more. It’s some sort of office. I stand near the glass doors. Somewhere near here is the actual spot where I was born. This is where you and I performed the prodigious feat of birth, Mum.

My two daughters were born here also. I attended both births so I know what it looks like, what a great splashing event it is, the strain, the splitting open, a head nudging into the light, then the whole thing squirting forward. Today’s my birthday. Sixty-six years ago, this is where it happened, Mum, where I slipped into the world and lay like a dazzled fish.

Dad came home from the war with shadows in his head. His favourite photo of you was of your smile. I got a photostat of that photo and inserted it in an old watercolour of gum trees to give your smile a bush setting. You were a country girl, Mum, shot hawks that came to steal chickens, walked paddocks with your father, gentle Jack Leary.

Dad saw life in shades of grey, you were vivid and full of colour. When I was young you and I butted heads over religion but by the end we just had fun. Every year on grand final day I rang you from the G, got among the crowd so you could hear the roar and get plugged into the electricity of the day.

It was Mum who taught me to kick a footy. She barracked for North Melbourne and hated Carlton because Wes Lofts played for Carlton and he hit Peter Hudson and Peter Hudson was Tasmanian. Mum was loyalty first, second and third. She couldn’t stand Liberals, including the one she called “Fatty” Downer. Guess what, Mum? Just before the US election, “Fatty” Downer announced he would’ve voted for Trump. No surprises there.

I met a bloke the other day who got a lift with you in the ‘60s on the West Coast of Tasmania in our EH Holden Station wagon. Coming round a mountain on a wet road, the old EH went into a slide. It happened more than 50 years ago but the bloke still went white at the memory. You drove your way out of it, Mum, laid off the brakes, hit the accelerator when needed, did it with style. He told me you drove trucks for the Army during the war. You didn’t, but, as one of my brothers said, you would have loved to.

You had an adventurous spirit but married a bloke who didn’t want to leave the backyard so you lived through the adventures of your kids. You loved what the Irish call the craic, Mum – the excitement of good talk, the communal contentment that sets a room humming. We made sure there was craic at your deathbed, Mum, lots of talk and chatter. “Thanks everyone,” you said, “I’ve had a lovely time”. They were your last words.

Michael Long says the silliest thing whitefellas say is that you can’t talk to the dead. His mother died when he was 13, he has a cup of tea with her every day. He says she was with him during the 1993 grand final when he won the Norm Smith Medal. He knows his mother was with him like he knows he wore the red and black of Essendon that day. I believe that stuff. That’s why I came to my birthplace today. I knew I’d find you here, Mum.

Beautiful article. Thanks for sharing your special memories