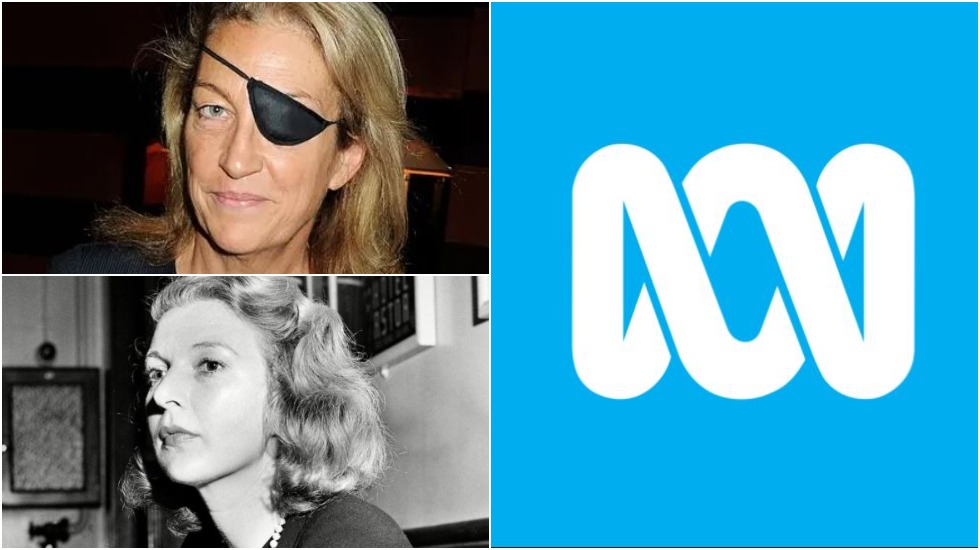

Renowned war correspondents, Marie Colvin (top left) and Martha Gellhorn (bottom left). Right, the ABC logo.

Back in my hitch-hiking days, the big trucks in passing sucked you in then blew you away. Big books do that to me – suck me in then blow me away. It doesn’t happen that often, but it did when I read “In Extremis – A Biography of War Correspondent Marie Colvin”. Significantly, the author was another woman war correspondent, Lindsey Hilsum.

I believe in journalism. Why? Because it represents such an obvious good cause. Because it gives people who aren’t at the scene of the action, whatever that action is – war, famine, earthquake, street protests, courts – an eye-witness account of what’s happening. Or, where an eye-witness account is not possible, a reasoned and informed view.

Of course journalism’s imperfect – its perspectives are inherently limited, it’s corruptible, it inclines to clichés of thought as well as language. But the fact is that, however imperfect journalism is, some journalists are recognised for doing it a whole lot better than others.

Rupert Murdoch owns the London “Sun”, which is commonly recognised as trash. Rupert Murdoch owns the “Sunday Times” which is not regarded as trash. American-born Marie Colvin worked for the “Sunday Times”.

You can argue endlessly about definitions of quality as it pertains to journalism. I say there are certain commonly held perceptions and that’s why right now, in this country, the issue of the ABC is critical.

The case for the ABC is not that it’s perfect – it’s manifestly not. The case is that what the ABC does well, it does better – and, in some cases, so much better – than its competitors. This is commonly understood. In survey after survey, the ABC has been voted the most trusted news source in Australia.

Marie Colvin was a great journalist. Why? Well, to begin with, no-one was braver, and this is to judge her relative to a particularly brave group of people – war correspondents.

She had a name for being braver than the men, but her “name” became a burden. With it came expectations. Having won a journalistic award for courage in 2000, she mused in her acceptance speech: “What is bravery? What is bravado?”

What takes this biography to a whole other level is Marie Colvin’s diaries. She reported her inner world with the same precision and candour that she reported the world outside her. Her private life was increasingly chaotic. She wanted two things – security in her home life and the freedom to report from war zones – but could never balance the two.

In Sri Lanka in 2001, reporting on atrocities against the Tamil population by government forces, she found herself abandoned and surrounded.

Having no other option, she stood up shouting, “Journalista! Journalista!”. A fragment from a rocket-propelled hand grenade fired in her direction by a government soldier – deliberately, she believed – penetrated her left eye.

Thereafter, she wore an eye patch, a sequinned one to parties, her parties being among the best in London. There were many lovers, several husbands, a growing alcohol problem, black depressions. The nightmare of what happened to her in Sri Lanka returned to her nightly in dreams. Not all of her behaviour was admirable. She was human.

In 2012, at the age of 56 and contrary to the will of the Syrian government, she managed entry into a suburb of the city of Homs where the Assad regime was slaughtering its own civilian population. After watching a baby die when shrapnel tore open its chest, Colvin did interviews with CNN and the BBC using a satellite phone. The regime tracked the signal and targeted the building she had called from.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Journalism, roughly speaking, is to literature what popular music is to the classics. Colvin was interesting in that regard. She wrote very simply. She slowed the pace of her delivery so much that the words actually meant what they said. Some of her sentences are no more than phrases. She crept into your consciousness like she crept into places she wasn’t supposed to go.

YouTube has the broadcasts she made from Homs the day before she was killed. She speaks with such composure, such authority. And she uses the first person. She says: “I saw”. No fancy footwork about objectivity. You see what she saw. That’s what her journalism was about. Bearing witness.

Colvin had been in Homs a few days earlier and got out. That had been considered a minor miracle. She chose to go back in. In 1999, she was credited with having saved a civilian population of 1500 in East Timor by refusing to abandon them.

The cameraman who went back into Homs with her was a Liverpudlian who’d been kicked out of the British paratroopers for carrying weed. The day before she was murdered, as they stood in the ruins of Homs, the bombardment going on around them, he asked her: “Would you do this if you weren’t paid to do it”. She replied, “Yeah”.

Unlike the confusion of her private life, right and wrong was a simple matter for her in war zones. And her “faith” – her word – was that if she got word out, the world would care.

When I talk in schools, I tell kids that just because you think that most journalism is trash, don’t make the mistake of thinking that good journalism doesn’t matter. It matters like clean air. In these increasingly uncertain times, we need the best intelligence we can possibly get.

Meanwhile, what we see at the ABC is the death of a thousand cuts. In the end it will become such a feeble version of itself, people won’t think it’s worth saving. Why would anyone want to kill off a country’s most trusted news service? To me, it’s a crime.

Marie Colvin’s hero was Martha Gellhorn, the only war correspondent to get ashore with the American servicemen on D-Day in June 1944.

She did it by dressing up as stretcher bearer. Saying she was the only war correspondent to land with the American Army on D-Day means no male American war correspondents landed with the American forces on D-Day. Imagine how that went down with the boys.

I heard an interview Martha Gellhorn gave late in life where she talked about covering the Spanish Civil War during the 1930s.

When fascist air attacks were imminent, she would open all the windows to prevent them blowing out and shattering once the bombs started landing. She’d then sit down with her back to the strongest wall she could find, place her portable gramophone beside her and then, as loud as she could, she would play Chopin’s “Nocturnes”. She called it her “act of defiance”.

And that’s the good news. You can’t kill off journalism. Every year, around the globe, dozens of journalists are murdered and hundreds are imprisoned. And still they keep coming.

This is terrific, and thanks Martin for using such outstanding women as examples of good and essential journalism. Makes the point also that cutting the ABC further restricts the opportunities for women journos who have long found it tough to cut through in the male dominated media world.

Another cogent piece. Inspired me to research.