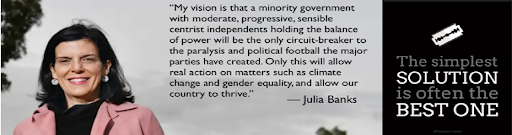

Former MP Julia Banks wants more independent members of parliament, without party affiliations. Photo: AAP

Former US President Barrack Obama believes that if women ran the world, it would be a better place.

“If more women were put in charge, there would be less war, kids would be better taken care of and there would be a general improvement in living standards and outcomes,” he said.

It turns out that Obama isn’t alone on this. A recent worldwide study of leaders finds women are considered more effective than male leaders in critical areas, such as self-development, the ability to accept and drive necessary change and – importantly – the ability to collaborate with, empower and enable colleagues in pursuit of that change.

For many women, it isn’t all about the accumulation of power and personal wealth. Having more women running things seems a no-brainer in a world where there’s far too much of that.

These are compelling reasons for a motivated, idea-driven woman to put her hand up for leadership, right?

You might want to think that through, given the experiences of former MP Julia Banks and women interviewed for the ABC mini-series Ms Represented – among others – of the Berlin Wall of obstacles women face in politics, all of them seemingly designed to discourage, demean, intimidate and perpetuate a male-centric political culture and concentration of power.

What I’m about to describe are actual experiences of women in politics, necessarily restricted by the word limit I’m given and the fact my blinkered left brain (a typical male trait) simply can’t do justice to it all.

IMAGE: Fox Broadcasting Company (The Simpsons, digitally-altered).

Women who try politics can expect an onslaught on their psyche, from the gratuitous to the downright egregious. First off, it’ll be the ‘well-meaning’ advice: “Make sure you wear your hair long, trade in those boots for Jo Mercer low heels and, for crying out aloud, quit smoking. It’s not lady-like.”

“What’s that? You need some campaign funds? Don’t you worry, darlin’. We’ll give you a raffle.”

“Oh, you want to talk policy on the campaign trail? You should be campaigning for better toilet blocks in the local shopping centre – stop rabbiting on about the economy. Leave that to the big boys.”

These are actual quotes (some paraphrased) from campaign advisers. No prizes for guessing the gender.

In the case of LNP pre-selections, a woman must often run the gauntlet of a party membership whose views on her ideal role often reside somewhere between Robert “I did but see her passing by” Menzies and Jackie “to the Moon!” Gleeson.

If they’re lucky enough to survive all this and actually make it into Parliament, that’s when things get serious.

My Footyology colleague, journalist, author, television and radio presenter Angela Pippos has experienced some of the sleazier manifestations of male privilege first hand, and – unlike yours truly – isn’t overly dependent on the linear, logical but limited left side of her brain to process it. So, when she says that misogyny and sexual misconduct of the kind recently exposed within the walls of Federal Parliament are in fact mechanisms to preserve “male privilege and workplace cultures that protect men and discourage women from speaking out”, you’d probably better listen.

“It’s not about sex, it’s about power”, Pippos wrote last November.

Of course, understanding why you’re being groped doesn’t make the experience any more tolerable. Just ask Julia Banks, who recounted such an incident while awaiting a crucial vote in the Prime Minister’s Wing of Parliament House.

“A cabinet minister sat on my right, sort of did that flippant ‘how are you’, and put his hand on my knee and ran it up the upper part of my leg,” Banks recalled. “If that happens to me [an accomplished corporate lawyer with what she saw as ‘power parity’ with the minister] you can only imagine what happens to people who don’t have that (power)”.

This inevitably brings us to Brittany Higgins, whose entree to the corridors of Parliamentary power was as a relatively powerless political staffer to ministers like Linda Reynolds. Higgins alleges that in late March 2019, she was raped on the couch in Reynolds’ ministerial office by a more senior male colleague.

A Federal Police investigation into the allegations is currently underway.

Inspired by Higgins’ going public, former Queensland Liberal senator Kate Sullivan came forward and recalled being “grabbed” by another senator, who “started to make like he was going to molest me.”

“I struggled, really hard, and he eventually let me go, and as I headed for the door he spat the word ‘bitch’ at me.”

Fairly or not, the ‘face’ of the government’s current sexual misconduct scandal is that of Industry, Science and Technology Minister Christian Porter. The former Attorney General was warned by ex-PM Malcolm Turnbull about questionable public behaviour with a young female staffer, was accused of repeated unwanted advances to women before and during his political career, and recently withdrew defamation action against the ABC over its coverage of a rape allegation (which he denies) dating back to 1988.

At the time of writing, Federal Police have been advised of some 19 incidents of sexual misconduct, ranging from harassment to assault, much of it inspired by Higgins going public. Given the obvious pressures not to come forward, one wonders if the true number will ever see the light of day.

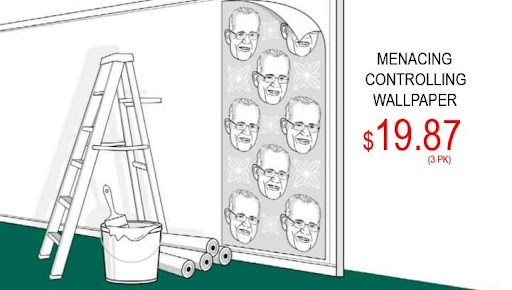

IMAGE: Ramona Quazzola, via Twitter

Not surprisingly, the response to these revelations, from men whose imperative is to preserve “male privilege and workplace cultures that protect men and discourage women from speaking out”, was one of damage control, with a fair helping of “shoot the messenger”.

Kate Sullivan kept her experience to herself, but soon realised that Senate colleagues’ attitudes to her had soured, and worried that whatever malicious gossip they’d heard would make it up the food chain to her then-leader, Andrew Peacock.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

“So I went to Peacock and told him about the incident … clearly he didn’t believe me, and he was kind of sizing me up” as to what her motives were, concerned not with Sullivan’s welfare, but his own. “That was one of the most devastating experiences of my life”, Sullivan told the ABC.

For her part, Banks was “drag(ged) through this sexist spectrum” as she sought to leave the LNP following Scott Morrison’s arrival at The Lodge. Unable to buy her with a cushy posting to New York, Banks told Crikey and The Age that Morrison and senior LNP figures “backgrounded” against her, coerced her via the use of intermediaries and labelled her a “rich bitch” a “bully”, a “nasty”, “crazy corporate” woman.

Throughout the ordeal, Morrison was always just out of sight, like “menacing, controlling wallpaper,” Banks recalled.

The “backgrounding” of journalists against Higgins, who Reynolds called a “lying cow”, and the mysterious cleaning of Reynolds’ office the day after the alleged rape are well-known. Only after the scandal exploded onto front pages did PM Scott Morrison seem to realise that “damage control” would, for once, have to include meeting the victim in late April, addressing her respectfully and – perhaps – doing something meaningful about what was a tsunami of turpitude.

Watch Morrison closely on this one. Porter remains a minister, there’s no move to further investigate his alleged transgressions and recent cabinet changes saw the promotion to Assistant Minister for Women of Senator Amanda Stoker – accused by Australian of the Year Grace Tame of supporting a traumatic “fake rape crisis tour” and a member of the Hillsong mega-church which invited to its Australian conference a controversial US preacher who once compared women to “penis-houses”.

Then there’s the phoenix-like resurrection (as Deputy Prime Minister, no less) of notorious philanderer and accused sexual harasser Barnaby Joyce. The boys’ club is back.

Of course, if you’re hellbent on preserving a parliamentary patriarchy, you’d better make sure the ramparts keeping women from a proper seat at the table are integral to the system and near-impossible to rip out.

Designed by blokes for blokes, politics is quite literally defined as “the activities associated with the governance of a country or area” and “activities aimed at improving someone’s status or increasing power.” You can’t achieve one without having the other.

Guess who’s usually better at the accumulation of power, having had millennia to perfect this dark art? That’s right: blokes.

Harvard Business School research reveals that women have more life goals, but fewer of them are focused on power. Women perceive professional power as less desirable than men do, are more wary than men of the negatives in attaining a high-power position and thus less likely than men to jump at opportunities for professional advancement.

There are exceptions, of course – Angela Merkel and Margaret Thatcher spring to mind – but the odds against women in politics are baked into a system which is adversarial in nature and has power at its core. Men tend to be okay at both, and they’ve a number of tricks up their sleeve to preserve the status quo, sexual misconduct among them.

Oh, and if you think Labor’s much better than the LNP on this, think again. Allegations ranging from sexual harassment to rape within Labor ranks have promulgated this year – overshadowed by the Higgins and Porter LNP scandals – with the former described by Labor’s deputy federal leader as an “indictment” on the party.

Yes, Labor’s policies aren’t stuck in the 1950s, and they’ve adopted quotas and other mechanisms to facilitate women in politics, but superimposing a regulatory framework on the longstanding, blokey culture of a party which also craves power and practices adversarial conflict resolution invites an incremental slog: “Twenty years of boredom”, as Leonard Cohen would put it.

As things stand, capable women like Tanya Plibersek have Buckley’s chance of wresting the Labor leadership away from the uninspiring Anthony Albanese. Oddly enough, the factional warlords who determine Labor’s leadership are mostly men.

IMAGE: Simon Holmes a Court, via Twitter.

It’s often said that if you put two people in a room, you get politics. Establishing pecking orders is part of the human condition, it seems, no matter how small the group.

Apply that logic to parties and parliaments and you’ve got yourself a maelstrom of political activity, largely aimed at the raw accumulation of power which men – no credit to them – are often better at.

The disadvantage for women is systemic and entrenched, in turn depriving society of what Obama says women bring to politics: “Less war, kids would be better taken care of and there would be a general improvement in living standards and outcomes.”

Perhaps the solution – within our lifetimes at least – is to reduce the impact of systems by having just one person in a room, instead of the groups and systems that inevitably lead to politics as usual.

What I’m talking about here are more independent members of parliament, without party affiliations. That’s what Julia Banks wants, along with the advent of minority governments we seem to be trending towards.

The idea is to have independents with the balance of power, leveraging minority governments of either hue towards sensible policies in areas such as climate change and, yes, gender equality. Perhaps then we can get to work on the systemic flaws which see conflict, avarice, the pursuit of power and sexual misconduct-as-control dug in to our politics like a paralysis tick.

An outcome like that is contingent on voter support, particularly in the inner suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne. Such support can be fickle, but as a simple Occam’s Razor solution, Banks’s idea is intriguing.

What’s the bet that most of these prospective, independent members would be women?

Utter tripe. Not within a bulls’ roar of real journalism. Just a series of re-cycled, unbalanced and un-tested claims mashed together to look like commentary.

Interesting reaction. Your manhood feeling a little challenged, Michael?

Michael, your ‘critique’ of my “recycled, unbalanced and untested claims” (most of them backed by research, if you care to read the article) is itself a bunch of recycled, unbalanced and untested claims.

I hope you see the irony.