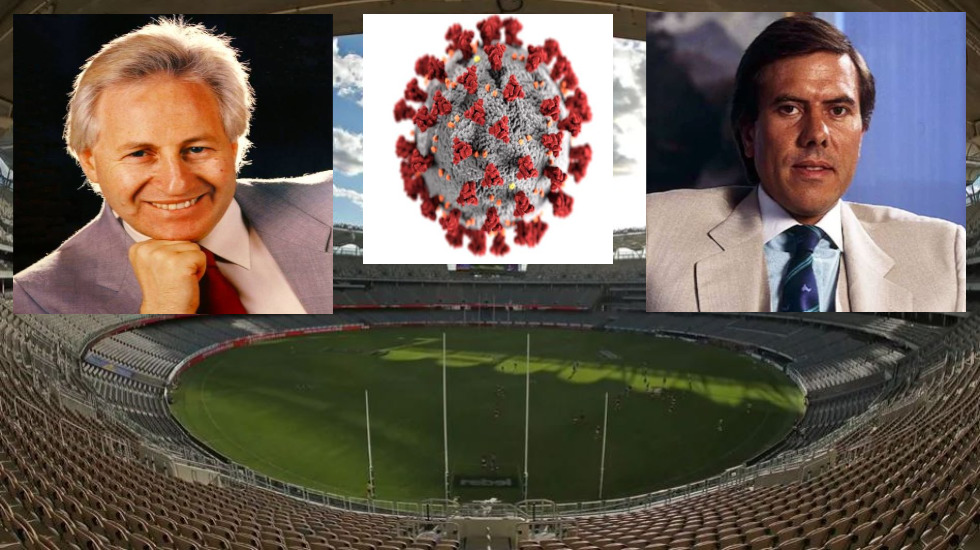

Geoffrey Edlesten (left) and Christopher Skase. Two cases of private ownership the AFL probably wouldn’t want to repeat.

It was the unexpected question from the man with the macchiato at the local cafe: “Who owns the AFL?”

Usually, it is: “Who is going to win the flag this year?” Or “who will be the first AFL coach to pack his bags? Will team X play finals? Who is going to ‘win’ the wooden spoon?

But this is probably a sign of the times when the financial torment of the continuing COVID pandemic has sports fans a little more focussed on who is pulling the strings at their sporting heartlands – and how deep their pockets run.

It is not the first time the question has been asked. Port Adelaide president David Koch took the theme to his baptism at AFL House in the summer of 2012-13 during his first AFL club presidents’ meeting. Then, the television-based financial guru was not wanting to make a point about who had their wallets (more so than their “skin”, as in their reputations) on the line at their AFL clubs.

Koch’s opening mantra as an AFL club president was based on bringing the “fun” back to the game – for the fans, the so-called traditional “owners” of the game, the leagues, the clubs. Australian football is the sport once defined by the saying “of the people, for the people”.

So who does own the AFL?

Is it the banks that have opened significant lines of credit to the AFL and several national league clubs to keep the cash flowing?

Ask Google – the “Mr Know-all” as Hall of Fame legend Barrie Robran calls the internet search engine – and the answer is, surprisingly, Gillon McLachlan. He is the AFL chief executive, but he does not own the 18-team national league. He is not Australia’s version of Bernie Ecclestone, the man who once owned Formula One car racing.

McLachlan is another of the many custodians who come and go in Australian football, all charged – and to be ultimately measured – by the philosophical demand they leave the game or their club better than how they found it.

This is an enormous challenge today.

The financial holes created by the COVID pandemic will test the AFL’s preference to work its own economy, built around three key financial taps – media rights, memberships and corporate backing (along with the significant government financial grants untapped during Andrew Demetriou’s reign as AFL chief executive).

In the 1980s, when the 12-team VFL faced a financial crisis that had half the competition technically insolvent, the lure of private ownership was too tempting to resist.

To quote Victoria’s Corporate Affairs commissioner Gordon Lewis from his letter to the VFL in 1985: “Of the 11 Victorian club companies it appears seven of them are technically insolvent. These clubs are Fitzroy, Geelong, Footscray, Collingwood, Melbourne, North Melbourne and Richmond.”

By then, South Melbourne had already become Sydney – and in 1985 an eccentric doctor, Geoffrey Edelsten, promised to pay $6.3 million to own the Swans.

The VFL-AFL never saw all that cash, reclaimed the Sydney-based licence and today is still the only registered voting member on the Swans’ business title. The private ownership model might have succeeded had the VFL endorsed the less flamboyant but more reliable Sellers brothers, Basil and Rex – both strong philanthropists to Australian football and cricket (with Rex having played Test cricket for Australia).

West Coast began its AFL story in 1986 with ownership tied to the Indian Pacific Limited concept that offered season tickets to those buying IPL investment packages starting at $1500. It was Australia’s attempt to make membership meaningful as it is with the 360,760 stockholders who make up the Green Bay Packers in American football’s professional NFL.

The financial books from West Coast’s opening season of 1987 were disastrous. After a multi-million dollar bail-out package from league headquarters, the Eagles were put in the hands of the West Australian Football Commission that bought a 75 per cent holding in IPL in 1989. The last of the minority shareholders in IPL were bought out in 2000.

Brisbane, the other non-Victorian expansion team for the 1987 season, had no joy with the Queensland consortium fronted by actor Paul Cronin and bankrolled by the dubious Christopher Skase.

By 1989, amid heavy financial losses and the collapse of the Quintex company that was supposed to pay Brisbane’s bills, major sponsor Reuben Pelerman became a white knight for two years until the Bears replicated the membership model that was in vogue virtually everywhere else in the league.

Richmond probably dodged a similar script in 1986-1987 when it appointed another of the high-flyers of the 1980s, West Australian tycoon Alan Bond, as club president – and avoided his vision of having Richmond listed on the Australian Stock Exchange while moving the Tigers from Punt Road in inner Melbourne to Brisbane.

North Melbourne did float on the share market by issuing three million shares – with the proviso there could not be one shareholder with controlling interest of the club – during 1986. Still, Carlton in 1991 did err in thinking it could take control of the Kangaroos – and strip the club of its stars – on buying the large share portfolio held by club leader Bob Ansett.

Fitzroy, a VFL foundation club, was sent to the wall (and perhaps wolves) in 1996 amid an attempt to find a financial lifeline while the death knell was struck by Nauru Insurance calling in its claims amid the Lions’ heavy and crippling debt count.

Australian football’s dabbling with private ownership models was short lived, a decade – and recently has been resisted after a South African group sought to invest in West Coast. But is private ownership in Australian football completely done?

The question is relevant because of the financial uncertainty from the COVID pandemic that has left a hole that could be as much as $100 million deep in AFL circles, even without counting the damage on the corners of the game’s pyramid, particularly the state leagues.

It is more relevant with the news that one of the world’s greatest sporting teams – rugby union’s All Blacks in New Zealand – is to sell a minority stake (15 per cent) to a technology investor, Silver Lake (the US private equity giant that has a stake in English Premier League club Manchester City and the UFC mixed martial arts empire). The deal would deliver $2 billion to New Zealand rugby at a time when the “game made in heaven” has found hell on Earth with COVID.

Australian sport is not as alluring as the big empires of American and European sport. But there are some interesting private ownership deals. In Australian basketball, the NBL found its saviour in Larry Kestelman and successful businessmen such as Grant Kelley, who is prepared to burn his wallet in keeping the Adelaide 36ers solvent and vibrant in South Australia. The American-born Jack Bendat is considered a shining example for private equity in sport with his ownership of the Perth Wildcats since 2007.

The A-League has the greatest puzzle with private ownership in Adelaide with the United franchise that is supposedly the “people’s club”. The point was reinforced when Adelaide United football director Bruce Djite took to Twitter to declare: “Whether it is good news, bad news or otherwise, transparency is an important value of Adelaide United. We are always willing and able to front up and answer questions. It’s important to keep our fans informed.”

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

The first response was from Bonita Mersiades, a former Football Australia staffer who now describes herself as a FIFA whistleblower: “So who owns and funds your club, Bruce? That is the first measure of transparency and it is still not answered.”

For the past two years, the question of who owns Adelaide United Football Club has remained unanswered by the club chairman, Dutchman Piet van der Pol.

He responds the club’s investors wish to remain private. It is a rich stand for a club that wants to be transparent to its members – and needs public money to upgrade its home venue at Hindmarsh Stadium. The South Australian taxpayer should know who is benefitting from public grants, particularly in the refit of Hindmarsh Stadium, the home field to the privately-owned Reds.

The concept of club membership at Adelaide United and beyond is loaded with myth, too. In many cases, fans are no more than ticket holders or “subscribers” rather than members with a say in the club’s destiny.

But how many AFL club members get a say?

When Footyology last month asked if non-Collingwood fans would have voted for Magpies president Eddie McGuire as their club’s leader, one frustrated Adelaide fan replied on Twitter: “No, because at the Adelaide Crows you don’t get a vote.”

Indeed, since the Adelaide Football Club was formed, each of its chairmen – Bob Hammond, Bob Campbell, Bill Sanders, Rob Chapman and now John Olsen – has never faced the Crows members to seek their endorsement as a board member through the ballot box. They were either endorsed by the original owners, the SANFL, or the current licence holder, the AFL Commission.

Same at Port Adelaide, where Koch was parachuted into the presidency by the AFL. He has never had his name on a ballot sheet for the Port Adelaide members, who have rarely had the chance to vote for a club director recently.

Former federal senator Chris Schacht has made it an annual mission at Crows’ members meetings to highlight the AFL – rather than the club membership – controls the Adelaide Football Club.

Schacht in July last year took issue with then-Adelaide chairman Rob Chapman inducting South Australian wine entrepreneur Warren Randall to the Crows board saying: “Warren Randall as an individual businessman is very successful in South Australia, Australia and internationally – and I congratulate him on his achievements in the wine industry.

“But why didn’t Mr Chapman put this vacancy on the Crows board before the 50,000 members to seek their views? It is because the Crows are run by the AFL Commission – and all Mr Chapman has to do is get the AFL Commission to endorse anyone he wants on the board. There is no consultation with the members.

“That is why more and more of the membership is questioning if this is their club. This is why more and more of the membership is questioning its relationship with the club. There is a governance problem.”

Then Olsen became Chapman’s successor with no member consultation and Schacht again had his ire raised by the AFL Commission having the only real vote of significance at Adelaide. Clearly, Crows members do not even own the destiny of their football club at board level.

Would Collingwood fans tolerate the AFL Commission being the only voice in deciding who succeeds McGuire as their club president? No, they would feel their club’s independence – and their part in the “ownership” of their club – is eroded.

Most – but not all – AFL clubs today have boards made up of directors elected by the members (a form of democracy that always works well for former players wanting to change their guernsey in the locker room for a suit in the board room). There also is the relatively new concept of directors with special skill sets (law, finance, marketing) being co-opted to the board without seeking member approval.

Again, more custodians rather than owners.

Who can make a sound call on the merit of private ownership in Australian football? Recently-retired Geelong Football Club president Colin Carter has a resume with all the appropriate qualities – he was a custodian of the game as an AFL commissioner for 15 years to 2008; he has served as Geelong president since 2011, and he is an expert in governance from his work as a management consultant with the Boston Consulting Group, where he is a founding partner of the company’s Australian arm.

Carter has a clear view on private equity in the AFL.

“I have always been opposed to private ownership in our sport,” Carter told Footyology. “I opposed it when we went national in 1985. But a little later, because the competition was broke, the commission went for private owners (Edelsten, Skase etc). While this helped to fund the new teams when the AFL didn’t have any money, it was later viewed as a bad move. And private ownership was dropped from the commission’s agenda.

“Private owners have different objectives. They won’t spend on development. They have incentives to increase attendance prices even if attendance is less (than expected on budgets).

“Our match-day prices are very modest on world standards because no one is calculating how much more money they can make. Private owners won’t want to take the game to places like Darwin, Launceston. They will want every game where their dollar is maximised.”

Many fans in world football – with the classic recent example being English club Newcastle United under the ownership of Mike Ashley – know exactly how Carter’s concerns can manifest at their clubs. Manchester United fans run bitter social media campaigns on the Glazers. And Arsenal devotees have made vocal protests on match day to prod club owner Stan Kroenke.

“Private ownership lessens the engagement with members – and remember that our great asset is the huge number of club members relative to our population size,” adds Carter.

“Our clubs only have three things to do with their ‘profits’ – improve facilities, reduce prices or pay the players more. Directors can assess these without also thinking of how to pay themselves more. Private ownership would take our competition into the ‘capital versus labour’ arena. That doesn’t help.

“Imagine if private ownership had been introduced a decade ago. Private investors would have made a fortune as the competition’s ‘value’ has been grown. But as things stand, that increase in ‘value’ is owned by the community. This is a far better outcome.

“You might get the impression that I am not a fan of introducing private ownership.”

The message is loud and clear. However, the question remains. Will the financial fall-out of COVID force Australian football to change the answer to the question of “who owns the AFL?”

Apparently, we all do. But as with everything in life, some have more power and say than others in this football community.