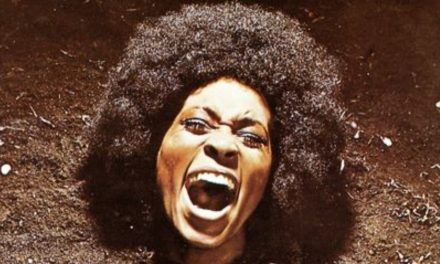

Footballers For The Future (from right): Gordie (capt), Basil, Flaps, Cuffie, Ozzie, Spook, Smithy. Photo: MATT NEWTON (Rummin Productions)

The Tasmanian University Football Club were the reigning amateur state premiers when I arrived in early 1972. They had some very good players and they had people like me who had no great gift for the game but were enthusiastic about playing it. Last weekend, seven of us gathered in Tasmania’s Tarkine wilderness at a site where a mining company predominantly owned by Chinese interests proposes building a dam to serve as a last resting place for its industrial waste. Five of us were issued with notices by the police saying that if we returned to the area within fourteen days we would be arrested.

It all started with Gordon Cuff. Two weeks ago, he and his wife Susy Aulich blocked the road to the dam site by chaining themselves to a gate. Arrested and charged, they are now out on bail. Gordon, also known as Gordie, was a much better player than I was, but we always got on. If we had gone to school together, we would have been made to sit apart. There’s an energy between us of the sort that leads young men to form rock bands. In 1979, Gordie was runner-up for the Hec Smith Medal, then one of the three major individual awards in Tasmanian footy. Carlton flew him over for a practice match but threw him back for being too small. He played in a Launceston Cricket Club team that included state players. As a schoolboy, he also showed promise as a diver.

His grandfather Leonard A. Cuff captained New Zealand at cricket before World War 1 and represented the country internationally as an athlete. At Uni, I played with Gordon’s older brother, Len. Len Cuff went beyond brave. Let’s be frank – the game back then was violent. When a Melbourne academic once asked me how long it took me to see through Marxism, I replied: “One quarter playing Claremont at Claremont”. That’s when I perceived that however much we might identify with the working class, there was no guarantee that the working class would identify with us. We were students, this was the era of the Vietnam War. Students were protesting the war, we played working class clubs that had players related to young men fighting and dying in Vietnam. One of our very best players, Greg “Dero” Rundle, was Tasmania’s first conscientious objector. Each week they came for him.

Yet this was also the theatre in which Len Cuff chose to perform. He played in state teams, but his fearless method of play meant he kept smashing parts of his body. In one of his damaged phases, he played with me in the lower grades. Essentially, Len was a clown who played the game at several different levels at once, starting dialogues and exchanges with opponents that the rest of us feared. Len had fun out there. One of the things I loved about the Uni footy club was the range of characters it contained. Now seven of us are back together, having seen little of one another for 40-odd years. Two of them, I am pretty sure, are or have been Liberals.

Gordie’s wife, Susy Aulich, is a small woman with a big personality and a quick wit, the sort that keeps you on your toes. Once Gordie and Susy were arrested, I knew I was going to have to do something but didn’t know what. Next thing I knew Gordie had organised six old Uni players, his brother Len among them, to go down the Tarkine with him. The big news was that Ozzie was coming.

Ozzie was the club captain when I arrived at the club aged 17 years and one month, eager and impressionable and up for a good time. I had long hair and used to run laps bare-footed because I got energy from the earth. The first night at training we were called into the centre of the ground by senior coach Brian “Cocky” Eade. Spying me and my bare feet on the edge of the circle, he cried out: “What the fuck have I got here??!!”. I became the club bard.

Ozzie said I was dangerous with words. I wanted to be dangerous with words like he was dangerous with the ball as he came out of the centre, making the play. Ozzie was an All-Australian amateur. He was quick, balanced. He had a short light step, could break left or right. He played in the centre and commanded the field. Geelong and Richmond flew him over for practice matches but he was in love with the girl he would marry and she was in Hobart.

My first game with Uni – my first game of men’s footy – was in the Thirds. I played well, surprisingly so. That night in the clubroom I made my way through the crush at the bar to get a beer and there was Ozzie working as a volunteer barman and I had my first lesson in the ethic of this football club. As he poured my beer, Ozzie (real name Terry Owens) said in a warm, encouraging way: “You played well today”. I felt, as they say, ten feet tall.

Ozzie’s a businessman who lives where he has always lived, Penguin, on the north-west coast. I’m surprised he’s coming, but delighted. Ozzie was a big part of my introduction to a club that was part of my life for the seven years between leaving school and leaving Tasmania to travel the world.

Spook was coming, too. He is called Spook because of some wildly successful seances he conducted in his student days in which strange lights appeared and material objects were said to leap around the room. Bespectacled, well-read and deliberate in manner, Spook’s real name is Gerard Leary. As a footballer, he was dark, compact and swift. He played senior football with both Ulverstone and Clarence before a chronic shoulder injury relegated him to the lower levels with the likes of me where he cannonballed through packs and played one-handed.

Steve Smith was also coming. An elegant and thoughtful footballer who could think very quickly, Smithy played in three state premierships with Uni as well as playing for Launceston in a grand final where they lost to City South, then the best team in Tasmania. He spent a year of his life in the highlands of Tasmania looking for the thylacine and, more recently, managed to keep the program aimed at saving the threatened Tasmanian Devil alive. The bail document from when he was arrested during the Franklin River campaign in the 1980s hangs proudly on his bedroom wall. A doctor of zoology, Steve Smith is a highly intelligent man who thinks and lives independently.

The sixth member of the group was Basil O’Halloran. His real name is Paul but his father was Basil so he’s Basil. We went to school together. He was gentle and good at sport and, notwithstanding the fact he was several years ahead of me, friendly. I always liked him. He became a teacher and for four years sat as a Green in the Tasmanian parliament. The school we attended has been the subject of a lot of publicity lately to do with sexual abuse. Two years ago, Basil and his brother Steve came out publicly about their experience of that. I’m writing a book on my schooldays which Basil read in draft form. There’s a sense in which we know each other at the sort of depth that brothers do.

The Tarkine campaign to date has been carried by the Bob Brown Foundation (BBF). There were about a dozen of them in their Tullah camp when I was there. Like the anarchists during the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s, they operate by consensus. To avoid argument, no-one speaks at their meetings, instead using sign language. On their way to Tullah, Gordon and Susy picked up a batch of vegan Anzac biscuits cooked for the young protesters by an elderly female supporter. If the young protestors were looking for a collective name, they could do worse than the Vegan Anzacs.

For 145 days straight they defended the forest before being evicted by police. When I was in camp they were making wedge-tailed eagle and masked owl costumes which they wore when they re-entered the Tarkine a few days later, climbing tall trees with shit cans and piss cans and food and sleeping bags so they have to be found and got out before work can continue. These individuals are easily mocked but perhaps, in 100 years, people will see the Vegan Anzacs as a tiny force who gallantly took on overwhelming odds – perhaps those same people will look at us and see a generation not remembered for anything it achieved but what it squandered and lost.

The Vegan Anzacs have lots of meetings. We’re squatting on a floor in a tent and I hear a male voice on the other side say: “I’m an older man and I have an older man’s bladder. If I am chained to a piece of machinery and it takes four or five hours for the police to get there, how do I go to the toilet?” Without missing a beat, the young woman conducting the meeting says he will be supplied with a nappy. As an older man with an older man’s bladder, I take a personal interest in the exchange and see that it will require considered thought. Finding yourself in the Tasmanian wilderness in winter, chained to a piece of heavy machinery, wearing a wet nap, waiting for the police, would not be the time to be having second thoughts.

We arrived at the entrance to the road being used by mining company MMG to build their tailings dam at about 8am on Thursday June 10. Gordie couldn’t come because it would violate his bail conditions. Len Cuff has a grandchild in Sweden and was concerned that a conviction could stop him getting into that country. That left five of us, six if you count the shiny red Sherrin that Gordie, ever playful, had brought for us to have a kick with. The Sherrin, that subversive bobbing bouncing symbol of fun, would play a critical part in the day’s drama.

We were not to the mouth of the wet, muddy road, when a tall lean man dressed in a dark blue uniform that caused us to initially mistake him for a policeman leapt into our path. Through a radio attached to his kit he was warning some other party that an intrusion was underway, simultaneously issuing a proclamation that we were trespassing.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Then he saw the footy in Ozzie’s hand. “That,” he cried, “cannot come in here!”. We continued to advance. The guard went for the ball but it was in the hands of our best player – Ozzie handballed it over the top to Spook coming through on the left, and we were through. I was slightly rueful. Had the footy been arrested, I might have had a story that would galvanise the nation.

We entered mixed rainforest, solid walls of leatherwood, sassafras and blackwood trees pierced here and there by incredibly tall straight eucalypts. The windy unsealed road was rough and muddy, the cold air delicious. About two kilometres down the road, we came to a second gate. Here two security guards and a couple of miners waited. The miners were not physically aggressive but did get close taking mug shots.

Here 73-year-old Paul Costin, who had volunteered to be arrested, took his stand, sitting down on a chair, forcing the police to come and physically remove him as the security guards are not legally empowered to do so. Paul is a former company director of a satellite broadcasting business. Steve Smith stayed so that there would be a witness to what ensued. The remaining four of us advanced.

Paul Costin (front), a 73-year-old former company director, volunteers to be arrested, at the second security gate. “The science is clear. So many things in my life are not going to be there for my children and their descendants,” he says. Photo: MATT NEWTON (Rummin Productions)

Again, a security man stood in our way issuing a loud warning, insisting we leave the area, while a young woman from the BBF insisted just as loudly that we were on public land. We continued our advance. Again, it happened that Ozzie had the footy. Again, the security guard went for the ball and again Ozzie handballed it to Spook. But the irony was that the artful Sherrin had drawn the security guard to our most elusive player.

The security guard looked like he was training for the days when being a security guard is an Olympic event. He was squat, muscular, maybe 40. He had his hands up like a basketball guard. Ozzie, now 70, was giving away 30 years but he seems as nimble as ever. There’s a story about Ozzie from when he was playing for Penguin on the north-west coast. Two Wynyard players came from either side to collect him, he waited to the last, suddenly withdrew and the pair knocked each other out.

Ozzie went left, the guard blocked. Ozzie went right, the same. Ozzie went far left, the guard skipped across using his arms to impede him in that annoying way Dylan Grimes does for Richmond (while otherwise being an excellent player). The young woman from the BBF was shouting, “This is an assault! This is an assault!”, but the sportswriter in me thought: “This is a contest”.

Ozzie told me later he did consider doing a blind turn. I would have paid money to see that. Instead, the young woman from the BBF demanded to see the guard’s ID, he was momentarily distracted, and Ozzie was through. I could see he was quite invigorated by the sport. I could also see how determined he was. I had not picked him as the sort of person who’d show up at an environmental action. He says his thinking on environmental issues is “180 degrees from what it used to be”. Becoming a grandfather seems to have been a part of that process.

Becoming a grandfather is a part of that process for a lot of people. By the time you get to our age, an increasing number of people you know are dead. Your own end is coming like a big full stop. At the same time you have these little people appearing at your feet. Indigenous cultures around the world say that the principal duty of humans of our age is to provide a sustainable environment for those who follow, just as it will be their duty one day to do the same for those who follow them. That’s how the whole system works.

Two-and-a-half-thousand years ago, Antisthenes the Greek philosopher said: “States fail when they cannot distinguish fools from serious men”. America went perilously close under their last president and Britain and Australia followed. We have a government that is utterly indifferent to the terminal damage being done to our major river system, the Murray Darling, source of sustainable life for eons. This same government pays someone to be a drought envoy and doesn’t even bother to require a report from him. My brother Richard’s recent book “Toxic”, on the Tasmanian salmon farming industry, basically makes the case that the history of that industry represents a wholesale failure in governance at every level – legislative, bureaucratic, regulatory. No-one has stepped forward to rebut his argument in a detailed or systematic way – the silence is deafening.

There’s four of us now – Ozzie, Spook, Basil and me. Initially, the road is relatively flat and it’s a pleasant walk. The boys discuss CO2 levels which have risen globally over the past 12 months due to wildfires – it had been assumed that COVID would have lowered them. We pass a eucalypt around 50 metres in height that has been left standing alone in a coup that has been logged. Basil, whose degree is in biology and geology, has studied carbon auditing. He estimates the tree would “lock up” between 100-200 tonnes of CO2 and says the average Australian produces 20 tonnes of CO2 a year.

It’s interesting to catch up with people after nearly 50 years. Basil’s the most obviously changed of us. As a young man, he was quiet socially – he says timid. At some point in his 30s he made the conscious decision “to step out” and say what he was thinking. He walks in the world with an unequivocal tread now.

We come into pure rainforest – no eucalypts – and a series of short sharp hills. Up and down, up and down … it’s like day five in the Tour de France. It is now I learn that Spook has run a record 36 Burnie 10s and Ozzie runs every morning. Basil, who walks “everywhere”, has calf muscles like knotted wire. I live on top of a steep hill and walk it regularly so I have some strength in my legs but, as in the Tour de France, it’s a question of pace. I drop off the back of the peloton by 10 or 15 metres. The one who notices is the one who always read people well, our captain Ozzie. He drops back and we walk together. We talk about cryptocurrencies and bitcoin, about which I know little and he knows plenty.

The lads – Ozzie, Smithy, Basil and Spook – at Gate 2 moments before the “Play of the Day”. Photo: MATT NEWTON (Rummin Productions)

Our goal is the construction site where the wilderness is being bulldozed apart. The entire space of the mining lease, according to Basil, is 280 hectares. The equivalent to 100 Melbourne Cricket Grounds, maybe more. I want to see the space that has been denuded. We’re within about 1.5 kilometres of our goal when the message comes through that the police are on their way.

They are remarkably good -tempered when they arrive, considering one has had to come from Strahan about 50 kilometres away. One of them, having heard that a Sherrin is on the loose in the Tarkine, arrives wearing a NSW State of Origin scarf pointing to the previous evening’s epic thrashing of the Maroons.

With them are two young men from MMG, the mining company. Neither is physically aggressive, but when one of them chooses to speak to us, he does so with cold disdain and arresting brevity. He says: “We are not doing anything unlawful. You are. That law was made in parliament. If you want to protest against that law, go and do it in Hobart outside Parliament House”. I’m still thinking about that. This is not a simple issue, or not for me. The tailings that will fill this dam will come from the Rosebery mine. My family lived in Rosebery for five years when I was a kid. I married a Rosebery girl … but now we have five grandkids.

Spook and Ozzie respond to the young men working for the mining company civilly and well. We’re not against the mine, they say, we’re not against you miners. The company has acknowledged there are other (more expensive) places where this dam could be sited. “We want it out of the wilderness,” says Spook.

We aren’t arrested, but we are apprehended and ordered to leave. We are prohibited from re-entering a defined area which is the mining lease plus 10 or so kilometres each way for 14 days. We are then put in police vehicles and transported back past the two security gates to where our cars are.

Back at the Tullah camp, there’s another meeting. I don’t go. The person a writer has to meet after an accumulation of experiences like this day’s is him or herself. The hard thinking has begun. Will I go down the Tarkine again? Maybe, maybe not. But participating in the action has impressed upon me the urgency of these matters. I’m reminded yet again of the 2016 report from the World Wildlife Fund for Nature that wildlife populations around the globe have plummeted nearly 70 per cent since 1970. On our watch, as it were.

In his football prime, Gordie Cuff was described by a sports journalist as a “ball of busy-ness”. He is that in all things. He is now “about getting people down the Tarkine” and, to this end, has organised Shane Howard to come next month, COVID providing. Shane wrote “Let the Franklin Flow”, the song that helped save the Franklin River, Tasmania’s great conservation battle of the early 1980s. Gordie’s also got Hazy coming.

Hazy is a Uni footy club legend. He coached the Fourths in which I played. He was an academic but, more to the point, he was the first intellectual I met who brought everything into one – art, footy, politics, the environment, cricket, books, music …

When Hazy (real name Pete Hay) left Tasmania in 1974 to take a position with the Whitlam Government in Canberra, it was my great honour to be made captain-coach of the Fourths. Later Hazy published my first book, a collection of poems. Still later he managed an itinerant cricket team called the Thylacinians, which toured Tasmania for 30 years, playing invitation matches. Hazy’s coming to the Tarkine with some of his cricketers. I am reliably advised he will be bringing a bat and ball. The solemn space that is the logging coup with the great gum stands alone would be considerably cheered up by a cricket match. Given the tricky nature of the wicket, the old master can be relied upon to bat first if he wins the toss.

*People wanting to get involved in the Tarkine campaign can contact Gordon Cuff on gordoncuff@hotmail.com

Great stuff! Smithy might remember that he has a unique Tasmanian animal named after him, the handsome but elusive Androchela smithi, a creature with such distinctive genitalia that a new genus was required to house it. It likely lingers in the Tarkine and has recently been spotted on the mainland.

Have a gander at http://v3.boldsystems.org/index.php/Taxbrowser_Taxonpage?taxid=361111

And https://bie.ala.org.au/species/urn:lsid:biodiversity.org.au:afd.taxon:31b14d8b-146f-49bc-a426-059443598e5a

Onya Flaps!! A really enjoyable read on a most depressing subject. The rainforests of Western Tasmania are precious and must be left alone to play their role in preserving the world environment for the future of humanity on Earth.

Great stuff Flaps best from Jill and Brownie

Thanks Neil Chirgwin for putting this incredibly fine writing about these talented, brave men.

Great read. Reposted on Facebook. And I hope Shane Howard pens something great. I also hope he can persuade those Madden cousins to visit as well. Maybe this campaign needs a ‘Sheedy’ and a ‘Long’ as well.

Excellent article Martin !!! Thank you all for caring about this precious place.

Great work guys! Just thinking back to the 1970 State Final – Eadie had concerns about many of the team didn’t keep to his travel schedule (playing Old Launcestinians in Launy) – due to the March in Hobart opposing the Government’s policy on Vietnam.

Good luck and more power to you ‘Tarkine Tigers ! Maintain the rage! Hope to be there with you when I return from the Bloomfield Track.

Great read Martin, I too am a concerned grandpa trying to do my bit in the beautiful Yarra Valley, I despair at what we are doing to our planet, Keep up the good fight and good luck to all of you, Steve

Lovely work Flaps , more power to you all !!