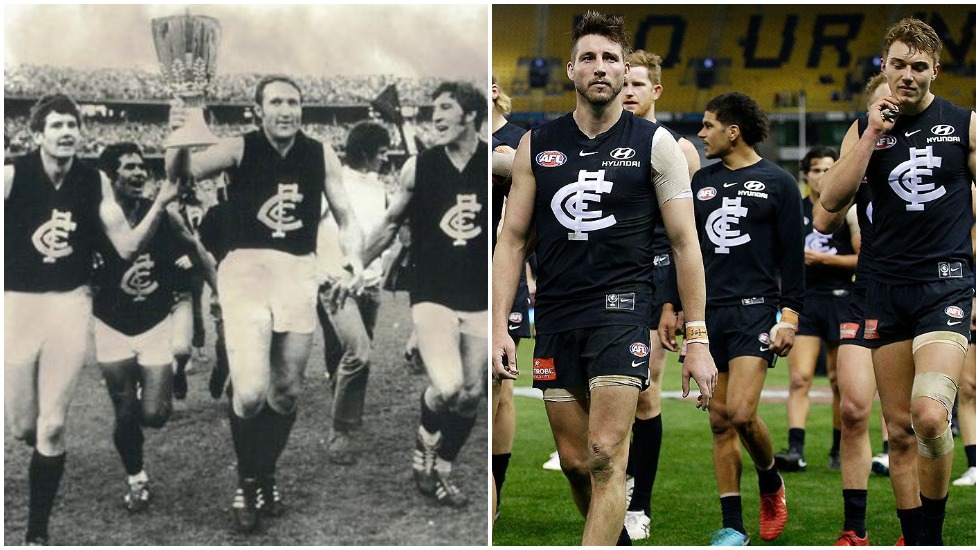

Then and now: Carlton celebrates winning the 1970 flag (left) and the modern-day Blues trudge off after another loss.

Four rounds of the AFL season have gone, and just one club, Carlton, remains without a win.

Football being the impatient business it is, that means, despite the fact the Blues have been in very winnable positions in at least three of those four defeats, they’ve been under the microscope all week.

With just three wins in the past 36 games, it’s perfectly natural that coach Brendon Bolton is copping heat, and when you’re an AFL coach these days, that means not just a forensic dissection of your tactics and selection, but your whole persona.

Criticisms of Bolton have centred around an alleged tendency to “over-coach”, to micro-manage, and a supposed failure to engage with his players in a meaningful manner beyond the intensity of football discussion.

As has been the case during other frequent barren stretches for the Blues the last decade or so, there’s also been the usual spirited debates about the quality of their recruiting and list management, and about just how switched-on and contemporary thinking is Carlton’s administration and board.

The various theories about all those factors are quite likely true, at least in part. Yet none in isolation are THE reason Carlton remains stuck in the worst period of its history. Because there very rarely is a single, simple explanation to not just a team, but a whole football club’s woes. Even when it comes to the bigger picture.

Carlton’s “Messiah complex” was a popular and valid point of discussion for some time as a one-time VFL power struggled to come to terms with an AFL environment, pursuing a series of quick fixes which ultimately made little difference, two coaches with tremendous records in Denis Pagan and Mick Malthouse perhaps the best examples.

But the Blues have tried valiantly for long enough now to eschew that tendency. Patience has become a byword of the club once so famously impatient, and after a 24-year flag drought, the longest in Carlton’s history, and its only five wooden spoons all delivered during the past 17 years, both club and supporters have become expert at it.

Other clubs have had far longer spells in the wilderness, of course, including the undisputed king of league football’s last 50 years, Hawthorn. The difference, though, between the Hawks and the Blues’ stories is obvious.

And maybe it’s also instructive. Perhaps, having learned the hard way what it takes to become successful, maintaining that success becomes an easier task than the reverse, that is, being a once-successful club learning to cope with the subsequent lack of it.

Hawthorn, along with North Melbourne and Footscray, entered the VFL in 1925. It served a long and largely unsuccessful apprenticeship, “winning” eight wooden spoons before finally winning its first premiership 36 years later in 1961.

And having absorbed the learnings of that tough upbringing and the lessons of mentors such as John Kennedy, Sandy Ferguson and Ron Cook, the Hawks’ record since has been extraordinary, 12 additional flags between 1971-2015 coming at the phenomenal rate of one every three-and-three-quarter years.

Carlton’s golden era between 1968-1987 delivered seven premierships and 10 grand final appearances in 20 seasons, a flag just on every three years. One premiership in the subsequent 32 years is a stark contrast indeed.

Given that context, it’s not so surprising that so many Carlton identities associated with those golden years played (and in some cases continue to play) influential roles in the club’s affairs. And however unintentionally, not always to the Blues’ benefit.

The end of that glorious run just as the AFL era was kicking off presented a club which, rather than embrace not only new thinking but new legislation regarding recruiting and player payments, sought to bend the new order to its will. Understandable at the time, but ultimately a battle it couldn’t, and didn’t win.

Carlton has spent most of the past 25 years catching up. But it’s not the only one-time juggernaut to have found clambering back to the top of the mountain more than a little difficult having already slid down from the summit.

It’s great modern rival Essendon has more similarities with the latter-day Carlton than it would like. The only other club to, like Carlton, have won 16 premierships in VFL/AFL company, the Bombers are in their 19th year without a flag, equal the longest drought in their history.

Like the Blues, they pushed the boundaries of legality in their desperation to remain a winner, paid a hefty price, and in some regards, are still paying it.

Richmond, meanwhile, didn’t break the rules, but as good as went broke “keeping up with the Joneses” in the mid-1980s after it had become used to living the good life up the top of the ladder with five premierships between 1967-80. It would be 37 years, of course, before the Tigers would really roar again.

And perhaps there’s no better example of the “hard to rise once you’ve been up” theory than Melbourne. The Demons won six premierships and played in eight grand finals over 11 seasons between 1954-64.

They extraordinarily sacked (temporarily) coaching legend Norm Smith midway through the following year when things weren’t going as well. And 55 years later, are still waiting for their next flag, having reached just two grand finals since then.

The frustrations of being down are felt even more keenly when there’s reminders of those salad days everywhere, be they on videotape or living, breathing relics whose opinions are still keenly sought and often acted upon, both inside and outside the club environment.

In Carlton’s case, perhaps Stephen Silvagni would have been the right choice anyway as list manager. But his legendary status at the club will undoubtedly make it harder to decide if he’s not.

Latter-day champion Chris Judd had hung up his boots just one week before becoming part of a panel to select the club’s coach after the sacking of Malthouse in 2015. And former champion player and premiership coach Robert Walls’s appointment this year to mentor Bolton is interesting.

No one who knows Walls even remotely would ever doubt his integrity. But would his long catalogue of Carlton connections have Bolton feeling reassured or more anxious?

And had Walls achieved exactly what he did with the Blues at, say, Essendon or Collingwood, would he have been considered for the role? Perhaps the Blues honestly can’t even answer that themselves.

Past success for proud clubs now in the doldrums sits like a brooding presence, a monument saying nothing, but the disapproval often inferred anyway, complicating life for those entrusted now with trying to replicate it.

Given exactly the same list and resources he has had for three seasons and a bit now at Carlton, but at, say, North Melbourne, St Kilda or the Western Bulldogs instead, would Bolton’s job have been as difficult? I tend to think not.

That’s not to absolve him from responsibility or blame for Carlton’s continued predicament. Nor Silvagni. Nor chairman Mark LoGiudice and his board.

But the slate for all of them can never be clean. And while Carlton wouldn’t for all the world trade in its tremendous historical success, it remains a somewhat uncomfortable bedfellow of any attempts to build from the ground up a healthy future.

*This article first appeared at INKL.