These numbers have become a distressing preoccupation for those who care about the violence against women epidemic.

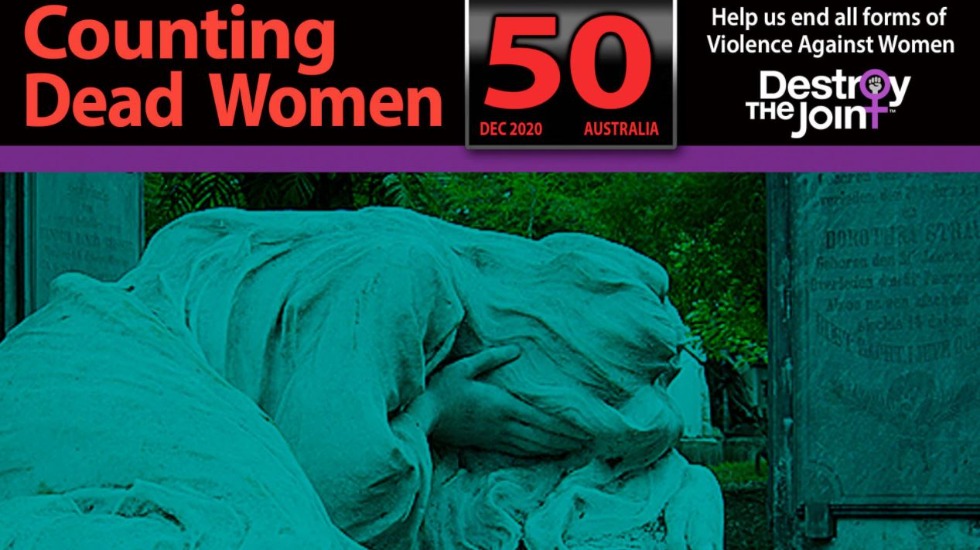

It’s week 50 of the year, and 50 women have died violently in this country.

Statistically, it’s unsurprising – on average, one woman a week is murdered by her current or former partner. This kind of violence is unimaginable, and yet it occurs with devastating regularity.

On November 30, three deaths were recorded in a single day. Shamefully, it wasn’t even front page news.

These numbers have become a distressing preoccupation for those of us who care about the violence against women epidemic, including academic and journalist Jenna Price, who researches, records and publishes every reported femicide in Australia as part of her “Counting Dead Women” project by anti-sexism group Destroy the Joint.

We live in the “lucky” country and we count dead women. Just let that sink in.

Every time I see the number of deaths go up by one, I feel sick to the stomach. When that feeling subsides, I find myself mourning for a woman I didn’t know, and for her children, if she had them. And then I get angry about the apathy and inaction.

Another woman is dead and what are we doing about it?

To quote political journalist Annabel Crabb: “If a man got killed by a shark every week, we’d probably arrange for the ocean to be drained.”

Hidden behind the rolling death count are incalculable numbers of women living in dangerous situations. Every two minutes in Australia, police are called to a domestic and family violence matter.

The reason I get stuck in the angry phase is because violence against women, whether it’s physical, sexual or psychological, is preventable if the will is there to do something about it.

But we need strong leadership.

It’s imperative our political leaders view and speak about violence against women as a national emergency, but regrettably, this doesn’t appear to be the case.

There was no new funding for domestic and family violence in this year’s Federal Budget, despite all the evidence that Covid-19 had exacerbated existing inequalities and contributed to a spike in violence against women.

In July, a survey by the Australian Institute of Criminology revealed almost 10 per cent of Australian women in a relationship had experienced domestic violence during the coronavirus pandemic.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Without adequate support, women have been made to bear the physical, emotional and financial cost of being trapped in a cycle of abuse and control at home, with no way out.

Family violence is one of the leading causes of homelessness for women and children, yet there wasn’t any additional funding in the budget for safe housing for victims/survivors.

Why isn’t the safety of women and children a priority?

Furthermore, a planned merger of the Family and Federal Courts poses a risk to women and children.

The Family Court was established in 1976 as a specialist, standalone court to deal only with family law matters. Family law experts fear a merger will have bad outcomes for children and families.

Law Council of Australia president Pauline Wright describes the merger as a “terrible gamble” and says: “Family violence best practice responses worldwide recommend enhancing, not undermining, family violence specialisation in courts.”

We should be listening to the people who work in the field.

But the disregard shown towards women isn’t just in the policy sphere. The day after three more women were murdered, Federal Communications Minister Paul Fletcher asked ABC chair Ita Buttrose to explain why the recent Four Corners report “Inside the Canberra Bubble” was considered newsworthy and in the public interest.

He either didn’t understand that the story was about male privilege, power imbalance and a workplace culture that protects men and discourages women from speaking out, or he chose not to grasp it.

And while we’re talking about culture, the minister should also take the time to research the link between disrespect and violence against women, too.

Until women have equality in all sectors of society, and until they’re safe inside and outside of their homes, we have to apply a gendered lens to policies, and we must demand more from those who are elected to represent us.

More broadly, we need a whole of community approach to tackle this insidious scourge. Research shows that gender inequality (where women do not have equal social status, power, resources or opportunities, and their voices, ideas and work are not valued equally by society) is a driver of violence against women.

We’ve all seen and heard “jokes” that disrespect and demean women online and in everyday life, “throwaway lines” that condone violence, snippets of toxic conversations that reveal coercion and control – all these expressions of sexism and inequality create the culture we live in.

Children see and hear this behaviour and think that it’s OK; they then repeat what they see and hear – and the cycle continues. As citizens, we all have a responsibility to challenge and call out these underlying drivers of violence to stop violence before it starts.

Christmas can be a difficult time for many people. For the families and friends of 50 women, this one will be particularly so.

And it’s time we all said enough is enough.

FAMILY AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE SUPPORT SERVICES

1800 Respect national helpline: 1800 737 732

Women’s Crisis Line: 1800 811 811

Men’s Referral Service: 1300 766 491

Lifeline (24-hour crisis line): 131 114

Relationships Australia: 1300 364 277