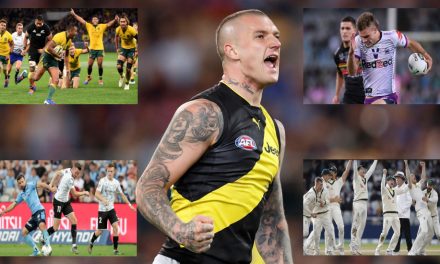

The Western Bulldogs ecstatic after their 2016 flag win, Adelaide dejected after their lost opportunity in 2017.

You’ve got to take your chances when they’re presented. It’s a mantra which can be applied to all manner of pursuits.

We’ve certainly heard enough of it this AFL season, with team after team costing themselves victories with poor conversion, 2019 one of the most inaccurate we’ve seen in a long time, Fremantle’s almost-comical scoreline of 2.19 last weekend against West Coast the low point.

Goalkicking is obviously the context in which you’ll most frequently hear the adage. Yet it’s just as apt when it comes to football’s bigger picture, too, and its most sought-after prize.

AFL premierships seem harder to win these days. There’s more clubs capable of winning them for a start. The landscape at the top of the ladder is more fluid, senior lists more vulnerable to injuries. And simply, you also need plenty of luck.

The last decade or so has been full of examples of teams which, quite literally, seized the day. And a few more hard luck stories involving those who didn’t. Indeed, we might be seeing another one of those right now.

Adelaide might have topped the 2017 premiership ladder only on percentage, but the Crows two years ago played some of the most scintillating football we’ve seen in the modern era.

They scored heavily, averaging nearly 110 points per game, nearly two goals per game more than their closest rival and five goals per game more than the current scoring average. Eddie Betts, Taylor Walker and Josh Jenkins combined that year for more than 150 goals.

They were frugal defensively, too, ranked fourth for fewest points conceded, and their pressure across the ground was superb, the Crows scoring more points from a greater percentage of opposition turnovers than any other team. After two thumping finals wins, they’d won 17 games by a whopping average of 53 points.

All of which counted for zip when Adelaide had a shocker on grand final day, completely out-bustled by a hungrier Richmond and beaten by eight goals. And increasingly for the Crows, it’s looking like that might have been that.

Last year was a shambles, Adelaide not even making the eight, the departures of an important defender in Jake Lever and small forward Charlie Cameron taking a toll, and the whole season played out against a backdrop of discontented rumblings stemming from a pre-season training camp gone wrong.

Now, the club appears a happier place again off the field. On it, however, the magic has gone. Eighth spot on the ladder at 8-7 is by no means a disaster, but this version of the Crows is a pale imitation of the version of 2017, confirmed again last Saturday when they were humiliated by Port Adelaide in a “Showdown” in which they could manage just one goal after half-time.

The defence isn’t as tight, the midfield nowhere near as prolific and the forward set-up a shadow of what it was, skipper Walker having struggled all year, Jenkins and Tom Lynch both having missed chunks of the season through injury, and at 32, Betts starting to feel the pinch.

That 110 points per game of 2017 looks the stuff of fantasy now, Adelaide ranked 10th for points scored at 79 per game, five goals per game less than back then.

In terms of personnel, there’s some tough decisions looming. Not just on Betts, but on ruckman Sam Jacobs, 31 and lately overlooked for the younger Reilly O’Brien. Big-name import Bryce Gibbs, at 30, is patently struggling and midfield mainstay Richard Douglas is 32.

In short, this is a team which won’t be making up for that missed opportunity of two years ago. And Adelaide, as a result, must look enviously across the state border at the Western Bulldogs.

Why? Because there’s no better example of a club which did manage to seize the moment, the very year before the Crows should have grabbed theirs.

The Bulldogs in a few weeks could conceivably become the first team in nearly 40 years to miss finals three years in a row after winning a premiership. But they’d be of a far sunnier disposition right now regardless.

Coach Luke Beveridge drew a line through the events of 2016 some time ago, recognising that while forever immortalised, that particular group of players wouldn’t be rising to such heights again, instead working, successfully it appears, at building the next Bulldog team capable of challenging.

The Bulldogs, who won a flag from seventh spot on the ladder, never reached the levels of September 2016 before that amazing month, and certainly haven’t threatened to since.

But for four glorious weeks a bit under three years ago, everything clicked, none the least on grand final day against Sydney, when they delivered the club’s second-ever premiership, and first for 62 years.

And there’s little doubt an entire support base would happily take three subsequent barren Septembers, and perhaps a few more, for the spoils of that day.

Geelong of 2008 might represent the best example of an opportunity missed after one of the most dominant seasons in history, the Cats winning 23 of 24 games until famously upset by Hawthorn on grand final day.

The Cats, of course, would rebound to win two of the next three flags, the first of those against a side with another heartbreaking tale, St Kilda, arguably a mere toe-poke (2009) and an erratic bounce of the football (2010) away from two successive premierships.

But Geelong’s redemption, significantly, came before the impact of two more teams in Gold Coast and Greater Western Sydney had been felt fully.

It came before that further stretching of the player talent pool left lists thinner at the bottom end, and increased the reliance on a stable and in-form senior core. And it came before the gap between best and worst on a given day had narrowed even further.

There’s a lot of prognostications, punditry and probabilities talked during 23 rounds of football and four weeks of finals. About the dominance the likes of Geelong have displayed thus far this season, or a resurgent Richmond with players back on deck might over the next couple of months.

Ultimately, though, it’s only how well opportunities are grasped between 2.30 and 5.10pm on September 28 which will really matter, regardless of what’s come before.

Those will determine not only who wins, but how we will come to view those who don’t, a tale which years later can be even more painful to revisit after the realisation there may only ever be one shot at it has sunk in. Just ask Adelaide.

*This article first appeared at INKL.