Matthew Nicks: “No, I didn’t think we’d bottom out. But I knew we would have our challenges.” Photo: AFL MEDIA

Robert Shaw left the Adelaide Football Club at the end of 1995 with the ultimate compliment. Crows chairman, the late Bob Hammond, acknowledged Shaw had in his two years baptised a handy group of promising young players to AFL action.

Simon Goodwin. Andrew McLeod. Tyson Edwards. Kane Johnson. Peter Vardy.

By the end of 1997, Hammond was celebrating the first of Adelaide’s back-to-back AFL premierships delivered by the “messiah” Malcolm Blight – the master of the “finishing class” in Adelaide.

What good did it do Shaw? He never coached in his own right in the AFL again.

Shaw is not alone in setting up a nursery at an AFL club and not seeing the project to its ultimate goal. Football’s graveyard is crowded with coaches who start rebuilds at AFL clubs and have the job finished by others … while never getting another assignment.

Matthew Primus at the “basket case” that was Port Adelaide before Ken Hinkley started the revival in 2013. The late Ken Judge in his ill-fated two-season stint at West Coast in 2000-2001. Peter Schwab at Hawthorn before the premiership dynasty was built by Alastair Clarkson from 2005.

At risk of joining this list is the newest coach in AFL ranks, Matthew Nicks at Adelaide.

Nicks lobbied hard – very hard – in October to replace Don Pyke at Adelaide to eagerly start his senior AFL coaching career with a three-year contract.

Those three years will coincide with the most-dramatic rebuild of the Crows player list … and there is no certainty Nicks will avoid joining Shaw, Gary Ayres and Brenton Sanderson in clearing their desks at Adelaide and not finding another senior job elsewhere in the big league.

This would not necessarily be a reflection of Nicks and his coaching – but of the AFL jungle and a football club that today is 22 years past its last premiership and falling behind, on the field, to its fierce in-town rival Port Adelaide.

Nicks took charge of a Crows team that ranked 12th and 11th of 18 with 22 wins from 44 matches in 2018-2019 – after claiming the minor premiership in 2017, but failing in the grand final to Richmond.

The quick fall of a red-hot premiership favourite in 2017 to a team that lost trust with its coach is one of the more bizarre cases of how the pressure to succeed can send a club down destructive paths.

Considering Nicks was joining a well-established club that described rebuilds as a “cop out”, the events of season 2020 at Adelaide do leave the prospect of history repeating. No win. First wooden spoon. And a rebuild club director Mark Ricciuto says is halfway to completion.

Some suggest the rebuild has only just begun and is at least a five-year project … another “five-year plan” for an AFL club that has not celebrated an AFL premiership for more than two decades. It has been a surprising fall, even by Blight’s reckoning.

“I expected them to improve on 10 wins from last year with a new coach and a new look,” Blight said. “And now they have decided to go young.”

Nicks is a “nursery” coach. And his destiny is in the hands of others. This is why Nicks’ introduction to AFL senior coaching will reflect much more than his ability to score wins.

Adelaide list manager Justin Reid and recruiting chief Hamish Ogilvie need to deliver on the greatest cache of draft picks ever assembled by the Crows, who also are building a significant salary cap buffer.

This follows clearing Sam Jacobs, Mitch McGovern, Jake Lever, Charlie Cameron, Alex Keath, Hugh Greenwood and Richard Douglas off the books (but not the salaries of Josh Jenkins and Eddie Betts in their moves to Geelong and Carlton this year). There also is to be a major salary cap gain – and a top-order draft pick – if free agent Brad Crouch moves on.

Even with a compromised draft in December, the Crows are anticipating Ogilvie will have five top-20 picks at the national recruiting lottery.

Adelaide chief executive Andrew Fagan, novice football chief Adam Kelly and Ricciuto need to structure – and fund in challenging economic times – a football program that gives Nicks a stronger coaching staff, both for match day and most critically in developing the new draftees in the Adelaide nursery.

And how do Ricciuto and co. calm a demanding supporter base – and the impatient corporate backers – who have not had to deal with tough times from their team, certainly not an uncompetitive team as the Crows have appeared so often this season?

“It takes patience, and time,” says Ricciuto. “We don’t believe there is another way to do it … you need to get quality draft picks into your club to form a nucleus of your side. That takes time.”

In its 30 years, Adelaide has had just one bottom-four finish – 14th of 17 in 2011 when Neil Craig’s highly competitive program crumbled without having delivered a flag, despite two grand campaigns in 2005-2006.

Since the 1997-98 premiership double, Adelaide has built its strong membership and corporate base with a solid “return on investment” on the field.

The Crows have missed just nine final series in that time (1999 under Blight, 2000 and 2004 under Ayres, 2010 and 2011 with Craig, 2013-14 under Sanderson and 2018 and last season with Pyke). There always has been the intent at Adelaide to rebound hard and fast after being idle during September’s top-eight finals.

This is the first time since the club’s formative years in 1994-96 with inaugural coach Graham Cornes and Shaw that Adelaide will have missed three consecutive final series.

If history was to repeat in the way that led Blight to follow Shaw at the end of 1996, there would be many agitators in Adelaide noting Hawthorn premiership coach Alastair Clarkson is out of contract at the same time Nicks’ term ends with the Crows.

Nicks joked after the loss to Melbourne at Adelaide Oval in round 10 he planned to be at the Adelaide Football Club for 20 years. No one has coached the Crows for more than seven years (Craig). Two coaches – Sanderson and Pyke – were marched from their offices with two seasons to serve on their contracts.

But what did Nicks truly expect on arriving at West Lakes in October to take charge of the biggest sporting club in his home city?

“No, I didn’t think we’d bottom out,” Nicks said. “But I knew we would have our challenges. I came in with complete clarity around where we were going as a club and the direction we needed to take to basically improve our list. We are in that process at the moment.

“Bottoming out is an interesting term … we are in transition; we are rebuilding our list. What comes with that is challenges.”

Nicks claimed the Adelaide job – ahead of Garry Hocking, Scott Burns and the reluctant Adam Kingsley – after establishing a strong resume as a development, assistant and senior assistant coach at Port Adelaide from 2011-2018, and after a 175-game career as a player with Sydney (1996-2005). He worked as the senior assistant coach at Greater Western Sydney last season.

“Matthew Nicks knew what he was in for,” says Ricciuto. “We were very clear what we wanted to do – rebuild; an aggressive rebuild. We knew we had to move on a few of our older players and we needed to try some of our younger players who have not been exposed to AFL football in the past couple of years.”

Nicks’ coaching resume does not include commanding a senior team, particularly an SANFL club, in his own right. His appeal to Adelaide – beyond the resume – was his strong record of building relationships, a key need at the Crows after the Pyke era ended with the playing group split into three factions.

Ricciuto noted from his background checks across the league that “no one had a bad word to say about Matty”. Today, the thought that nice guys do finish last haunts Nicks – and gives a misleading impression on his strength to deliver harsh messages when a team or player needs to be brought back into line.

Nicks is not short of advice in Adelaide, particularly in the public and media space, where former Crows coaches Cornes and Blight have strong platforms.

“He needs to do what he believes in,” Blight said. “But he won’t ask me, so I don’t have to worry about it.”

Cornes recently declared Nicks needed to stop being “Mr Nice Guy”. That image completely vanished at three quarter-time in the home clash with Collingwood last week at Adelaide Oval, when Nicks did not hide his frustration.

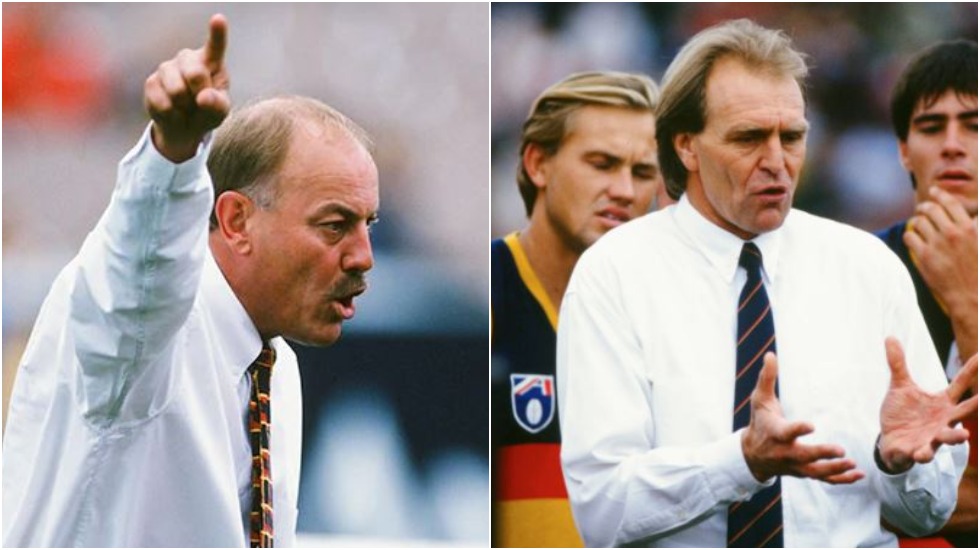

Nicks is not short of advice in Adelaide, where former Crows coaches Malcolm Blight (left) and Graham Cornes have strong media platforms.

And the body language among his assistant coaches – as captured so vividly by the Fox Footy cameras during the team’s error-riddled collapse in the second half – highlighted how the pressure valve blew open after another last-quarter fade-out.

Nicks started the season with his football department spend carrying the burden of pay outs to Pyke (who had two years on his contract); football manager Brett Burton, who had his legal claim made by a record of scoring highly in all his annual reviews with club chief Andrew Fagan; and midfield coach and senior assistant Scott Camporeale.

Nicks is the least resourced Crows coach since the AFL professional era kicked in during the mid-to-late 1990s. It is far from the image Cornes would once portray of an Adelaide coach “never wanting for anything”.

Port Adelaide premiership midfielder and multi-media critic Kane Cornes says Nicks has been “hung out to dry” by Adelaide failing to support him with suitable staff, particularly with line coaches. This becomes more challenging with the $3.5 million cut in football department spending next year as the pain from the COVID pandemic hits across the national competition.

Nicks is expected to target Port Adelaide forwards coach Nathan Bassett, a former Crows defender and a premiership coach at SANFL club Norwood. He is planning to reconstruct his football coaches with multi-tasking assistants.

“They will be so much more than line coaches – they will need a high skill set (to take on more roles),” Nicks said.

But there is still no suggestion of hiring a senior assistant, such as current Essendon coach John Worsfold, who guided interim coach Scott Camporeale after the Crows were rocked by the death of coach Phil Walsh midway through 2015.

And Blight says Nicks should not seek an old hand to be at his right side.

“I recently asked an Adelaide 36ers basketball coach about a senior assistant,” Blight said. “He said: ‘No, if you can’t do it, you can’t do it. Doesn’t matter who you have got there, if you are going to be a coach you have to learn to do it. Yes, sometimes you might need some help, but you have to be the one to do it’. I am of that mind too. It has to be you.

“Coaching is about having a very good team that you (as a coach) make better.”

Nicks does not have that very good team.

Finding the player talent to nurture into a progressive AFL line-up rests with Ricciuto, Reid and Ogilvie.

“We need to continue to get to the draft for the next year or two,” Ricciuto says. “We need to follow the footpath of a few other clubs in the competition that are now starting to play pretty exciting football.

“We don’t believe there is another way of doing it. You need to get quality draft picks into your club to form the nucleus of your side and that takes time and patience. That is exactly what we are doing at the Adelaide Football Club at the moment.”

No-one can fairly judge Nicks in 2020. But that honeymoon period – as rough as it has been for Nicks this year – always fades. The game lacks patience.

If Nicks gets through the 2021 and 2022 season showing significant progress – as Clarkson did at Hawthorn in 2005 and 2006 – he would avoid the Shaw ending to finish the job he has started.

But there is no guarantee with anything at Adelaide today – the rebuild, the post-COVID refit of the football program, or of Nick’s wish to still be coaching the Crows in 20 years’ time.

For the next two years Nicks will make a fascinating study of a novice coach and a club being tested both internally and externally, particularly if the membership starts to vacate seats at Adelaide Oval. Fagan once declared he would lose sleep if the Crows drew less than 45,000 to their home games at the 53,500-capacity Adelaide Oval.

Nicks is in the hottest seat of all.

I would be fixing the culture first. No mention of the toll the murder of Phil Walsh must have had, on the players and the Psyche.

Great article , Adelaide teams are tarely discussed in Victoria and it gives an insight into the perilous state of footy at the moment. If a poweful club like the Crows can fall so rapidly , then it sends a warning to the minnows of the comp. Then again Port turned things around very rapidly . Interesting times.

Such a powerful club with seemingly endless resources to fall this low is really quite shocking. West Coast has bottomed out before but very briefly on the back of excellent recruiting. The Crows look way off and have issues retaining players. A lack of club culture might be a factor as Port have no issues in player retention so you cant blame the Adelaide/homesick factor.