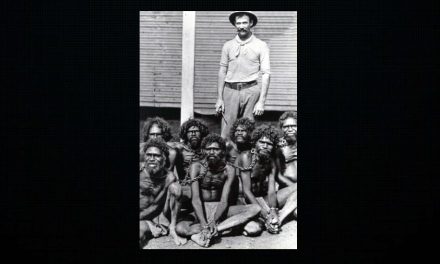

New York’s Fearless Girl statue adorned with a lace collar honouring US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

There’s something powerful that unites women all over the world. It’s an intangible force, not in a George Lucas kind of way – it’s real for every woman who feels it, and it exists because of a very real problem. Inequality.

At the heart of this bond is the ongoing pursuit of equality which, in Australia, began with nineteenth century suffragists staring down convention to win the right to vote. And this pursuit of fairness, across all parts of society, continues today.

It’s often described as the fight for equality, and it is an exhausting, and at times despairing, fight, but it’s also more than that – the sisterhood is joyous, the gains along the way, whether they be made in parliament, on the sporting field or in the boardroom, are joyous, and when you get them, you celebrate them because, lord knows, they can be few and far between.

What connects us is a desire for change – a desire to live in a world where women have equal pay and opportunities; where domestic labour is divided evenly; where access to childcare is affordable, where women can live without rape, sexual assault, violence, sexual harassment and sexism, where they can feel safe inside and outside of their homes, and where they have the right to control their own bodies.

On 18 September, when U.S Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died, I felt the feminist force field in all her unbridled glory.

Ginsburg was a pioneer for gender equality and a “a tireless and resolute champion of justice”. President Trump has selected deeply conservative federal appeals court judge Amy Coney Barrett to fill Ginsburg’s seat on the Supreme Court and it’s a decision that, if confirmed by the Senate, could have serious repercussions for hard-fought abortion rights.

As I sat reading about the potential consequences of Ginsburg’s death, a photo popped up in my Twitter feed that made everything feel good (albeit briefly).

Someone had placed a lace collar on the Fearless Girl statue, which stands across from the New York Stock Exchange. Ginsburg’s jabots were her trademark and seen by many as a statement to “unapologetically feminise” the masculine black robes of her profession. What a fitting accessory to an already fabulous statue – an all-too-rare statue.

In nearly every country in the world, women make up just two to three per cent of the public statues. In Australia, just under four per cent of all statues represent historical female figures.

I see dead (white) men everywhere. We have more statues of animals than we do of women, and a smorgasbord of over-sized food (all of which I like by the way) – The Big Banana, The Big Prawn, The Big Murray Cod, The Big Merino, The Big Macadamia Nut, The Big Pineapple, and on and on.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

According to statuesforequality.com, there are currently 580 statues in Melbourne, and only one per cent are of real women on their own in a public space. That’s a grand total of five women.

Where are the women who made Australia the country it is today? Where are the suffragists? (In 1894, South Australian women became the first in the world to not only vote but also stand for parliament, and this set the rest of the country in motion).

Catherine Helen Spence should not be on her own. Where are the women from literature, science, sport, feminism, indigenous rights and the arts who shaped our nation?

Public statues reflect how a society values its women and men. Excluding women sends the message that their contributions throughout history are not as important as those of men, and this message seeps into the public consciousness, and feeds a belief system that places white men at the top of everything.

Lining a boulevard exclusively with men in gleaming shades of bronze gives us an incomplete and skewed version of our history. And, if there are no women to literally look up to, how will boys and girls see the sexes as equal?

We need statues of women so we can find out about their stories, celebrate their lesser-known or unknown accomplishments and shift attitudes. Statues are important.

A statue honouring Justice Ginsburg will be unveiled on 15 March 2021, in her birthplace, Brooklyn.

To celebrate this victory, and get the conversation started closer to home, I’m going to nominate a few Australian women who deserve to be immortalised in bronze too.

Like suffragist Vida Goldstein, Olympic gold medallist Cathy Freeman, Professor Fiona Wood, who invented spray-on skin for burns victims, equal pay campaigner Zelda D’Aprano, (“Operation Zelda” kicked off in March this year and is the first statue of a campaign called “A Monument of One’s Own” by historian Professor Clare Wright and journalist Kristine Ziwica), and former test cricketer Betty Wilson.

Wilson was the first Australian woman to score a Test century against England. In 1958, she became the first cricketer, male or female, to take 10 wickets and score a century in the same Test – and she’s been inducted into both the ICC Cricket Hall of Fame and the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame. When Wilson died, aged 88 in 2010, she was acclaimed the finest of all women cricketers.

We should all know Betty Wilson’s story – it should be celebrated and passed down like Sir Don Bradman’s story, Keith Miller’s story, Richie Benaud’s story – but we don’t, because women’s sporting achievements have been hidden throughout history, as have the achievements of so many women.

Smashing the bronze ceiling will help fix this monument(al) gap.

Thanks Angela. This is a terrific and timely piece. This morning I see calls for a monument to Susan Ryan, which would be equally deserved. Thinking too about virtual statues. Maybe next year – which marks the centenary of the first woman elected to an Australian Parliament (Edith Cowan in WA) – our national collecting institutions could mark the occasion with online exhibitions etc celebrating key women in Oz history. Time to smash the ceinlings on every platform and plinth!