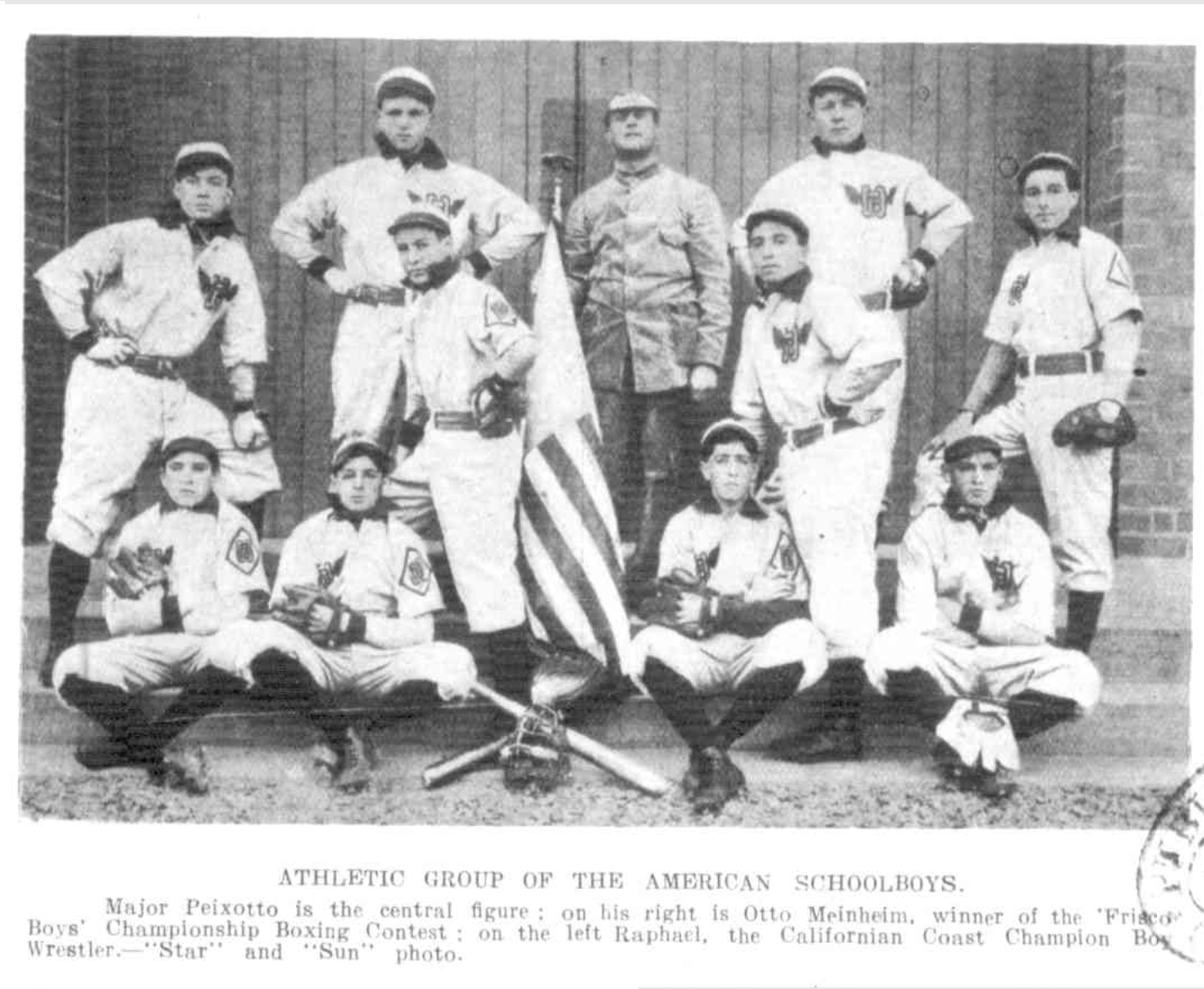

Members of the Columbia Park Boys’ Club baseball team posing for a photo in 1915.

Aussie Rules is yet to take off anywhere outside of Australia, despite many attempts.

A thriving and expanding competition on foreign soil just hasn’t happened, but not for a lack of trying.

It is hard, then, to believe that those running the game once shunned a visitor of substantial means and merit, who came to our shores prepared to master Aussie Rules and return to San Francisco and launch it there.

American philanthropist Major Sidney Peixotto (pronounced Pe-Show-Tow) in 1909 toured Australia with 40 fine sportsmen.

Peixotto’s troop came here to live and breathe Australian Rules football. The tour went many months, far longer than was first expected, and the Americans could play – they often beat us Aussies at our own game – but sadly, the effort was all in vain.

The tour was no spur of the moment idea; the backstory is complex.

In 1905 the President of the United States, Theodore ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt, was furious. The violence within American football had totalled 18 deaths, along with countless injuries, in that year alone.

Roosevelt openly sought an alternative to his country’s dangerous, deadly, version of football. The Victorian Football League (VFL) contacted him and offered Aussie Rules as a solution.

But the VFL did not stop there, it boldly sent promotional packages of how to play Australian Rules football to more than 60 American universities, many of which were dropping American football, and suggested they trial the safer Australian football variant.

Historians believe that this action backfired. The VFL had stung rugby union into action. With better promotional tools, rugby, not Aussie Rules, within a few years would replace American football as an inter-collegiate sport.

Around the time of Roosevelt’s cry for help, some fine ex-VFL footballers, coincidentally based in San Francisco, were agitating for Australian Rules to be played there. Major Sidney Peixotto, also of the bay region, had founded, and still presided over, the Columbia Park Boys’ Club – a club that gave opportunities to street kids from the poorer parts of town.

Peixotto’s benevolence went beyond his youth welfare work and, as a high-ranking American athletics administrator, he had received the VFL’s propaganda pamphlets.

With the assistance of the ex-Aussie Rules players residing in San Francisco, some experimental practice sessions were organised, and Peixotto’s curiosity of the Australian game intensified.

Subsequently, the Australasian Football Council (AFC) held meetings during their epic 1908 Australasian Football Jubilee, when they brought together delegates from all the Australian footballing states, and New Zealand, in Melbourne, for not just a football tournament, but to align all rules, and target the code’s future direction.

One possible path included global expansion; a call taken on by powerful Western Australian football administrator Mr JJ Simons who began making plans for a promotional tour of Great Britain. Simons too had encouraged his like-minded American friend, Peixotto, to hopefully transplant the code into the USA.

But as 1908 drew towards its end, Simons could not accumulate the immense finances a British tour would require, and the optimism surrounding American colleges was gone. Australian Rules proved unable to emulate the travelling spectacle of national rugby tours, and the passions and patriotic loyalties they could stir. To be able to vent and sneer at a national English or French team proved too much. The highly contextual suburban-bred rivalries of Melbourne footy have always proven hard to replicate in foreign stadiums.

A Melbourne Herald cartoon that was published when Peixotto went through Melbourne. It is amongst the most famous of the Herald cartoons.

Peixotto remained stoic. Undeterred, and with the blessing of Simons, he secured commitments for his travelling troop to be accommodated in cities across the antipodes, except for Victoria, where Con Hickey, the Gil McLachlan of that time, oversaw the VFL’s daily business.

Fortunately, the principal of Melbourne’s Wesley College offered to house and feed all of the boys for one week. Peixotto’s itinerary would be able to enjoy at least one week at the birthplace of the Australian game, but the indifference Peixotto encountered in Victoria would have consequences.

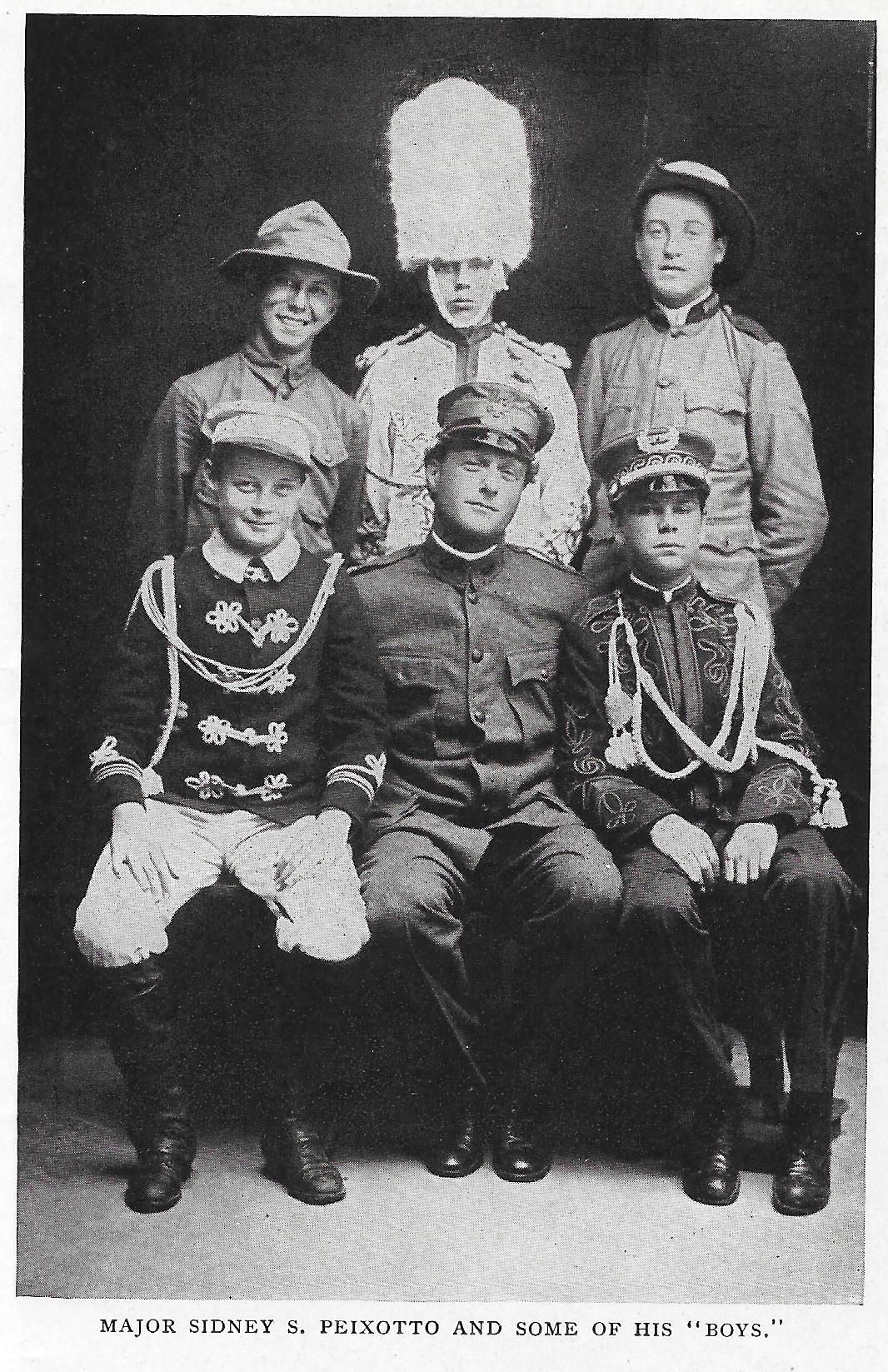

Peixotto’s design for his Columbia Park Boys’ Club stemmed from his intrigue of people we now know as social workers, who were tackling 1870s issues of gang violence and dishevelled youth.

Peixotto thought he could help youngsters rise from the squalor he witnessed. He established the Columbia Park Boys Club to offer light military-style training, and sport, art, theatrical, and musical tuition.

Additionally, the club provided extensive outdoor and work-related activities, and its vigorous alumni assisted with employment, in a better example of ‘jobs for the boys’. The Boy Scout movement, founded later in 1907, strikes an uncanny resemblance to what Peixotto had first created years earlier.

For its first 10 years, Peixotto, and his uniformed boys, had suffered merciless taunting and teasing in unsafe downtrodden streets, especially from the Ricon Hill Gang, in an area known as “South of the Slot”.

Those under his guidance, boys who were once juvenile delinquents, thrived however, and sung Peixotto’s and his club’s praises. By 1909 the Columbia Park Boys Club proudly boasted 300 members and 4000 boys had already passed through its ranks.

Peixotto would be decorated by the city of San Francisco and feted by American Presidents. His altruistic work with troublesome youth became a model admired the world over.

The 1909 tour wasn’t Peixotto’s first. His troop had covered California by foot, and had travelled to London. The curiosity these highly-skilled boys aroused in cities large, and small, generated sufficient finances to cover their expense. Peixotto very much adhered to a mantra of paying your own way.

It is hard to find any evidence of Peixotto exploiting the boys in his care for his own pleasure, or to procure for himself heavy financial rewards. The successful Columbia Park alumnus that followed in his wake likely attests to his respectful behaviour.

Peixotto’s Columbia Park club survives to this day, his reputation unsullied.

Every one of Peixotto’s 1909 charges, all 40 boys, had lost their homes to San Francisco’s catastrophic 1906 earthquake.

Peixotto and his entourage were certain to pique interest in entertainment-starved isolated Australian and Pacific communities. The troop delivered marching demonstrations, singing, dramatic performances, and vaudevillian skits.

Every boy played a musical instrument, thus the entertainment they offered included a loud 40-piece brass band. With unbridled enthusiasm, after two years of planning, Peixoto and the 40 Columbia Park Boys shipped off into the Pacific on Saturday May 22, 1909, and headed down under.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

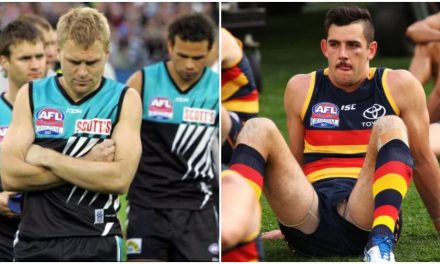

Peixotto with members of the Columbia Park Boys’ Club.

The tourists first arrived in Wellington, in mid-June, via Tahiti. The press covered their every move, and Peixotto too came prepared with extended pre-written press statements.

At a civic reception immediate to his arrival, he told the Wellington press the purpose of the trip: “We have really come from San Francisco to play football in Australia … our idea is to mingle with the Australian boys and learn the Victorian game of football, which we consider would be an ideal game for boys on the Pacific coast.”

At whatever town, from a capital city the size of Sydney, to North Island’s rural Taihape, civic receptions greeted the Columbia Park Boys, who were addressed by Prime Ministers, premiers, consuls, mayors and the highest-ranking available dignitaries. Peixotto, a captivating orator, was at home amongst such company.

The New Zealand stay was brief. The tourists delivered hearty energetic musical and theatrical performances, amidst much to-and-fro speech making.

The visited cities went out of their way to accommodate the Americans, they were taken to every tourist attraction. After one week, the large ensemble departed to Sydney where sporting contests awaited.

Soon after their Australian arrival, the teenagers beat the best senior baseball team in New South Wales, Paddington, 2-0; in front of an enthralled Sydney Cricket Ground audience.

The following Wednesday they tackled a combined Sydney schoolboys’ team, their first ever Australian Rules match, where they received a rude shock.

The local Sydney boys ran riot in the first half to lead 68 to one. To the Americans’ credit, they reset themselves at half-time, and only ended up 50-point losers, 13.15.93 to 6.7.43. The Sydney Australian Rules Football competition had been suspended for that Saturday; it had become obvious that Sydney’s footy community wanted to see the visiting Americans themselves.

Three days later the two same teams went at it again, but the Columbia Park Boys sunk a bit, losing 12.12.84 to 2.6.18. Peixotto lamented that the stunning NSW coastline had offered too much excitement, and that his boys needed to knuckle down and get stuck into some ‘hard work’ – very much another Peixotto mantra.

The travelling circus then headed to Melbourne, but not before a 10-day camping jaunt through the Goulburn Yass region. Every day brought the chance of a sporting contest and time to entertain, no matter how remote their location.

In Melbourne, the tourists received some badly needed help, some serious football instruction. Alec “Joker” Hall was a seasoned, hardened football coach – there was no better person to train the boys.

As their technical advisor, he taught the American boys every facet of the game. Fortunately, “Joker” has left us with some impressions of this time, this excerpt is from The Melbourne Herald on August 14, 1925:

Those boys were champions of their state in baseball and basketball and won big prizes. As their football instructor here, I came in close contact with them daily, and soon learned how smart they were. They took a liking to our game from word ‘Go,’ became very apt pupils, and played against school teams all over Australia. They won 28 of 33 games played, and would have won more if they had not to leave out the bigger boys whose average age was 15. They took a great interest in the drop-kick and were soon specialising in it…

I had them out at East Melbourne ground for an hour-and-a-half one afternoon, and was wondering when they would get tired.

From an article in a 1909 edition of Punch magazine, Peixotto is surrounded by some of America’s best young combat sport practitioners of the time.

“Joker” Hall reversed the Americans’ form, they rarely lost a match after their horror Sydney initiation. With Peixotto somehow managing to keep the finances afloat, the months soon rolled past.

Western Australian was so enjoyable they stayed two months.

The travellers went back and forth across Australia, and spent weeks in the capital cities of Sydney, Adelaide, Perth, Melbourne, Brisbane and Hobart as well as lesser-known places such as Narrogin, Northam, Bunbury, Albany, the Western Australian goldfields, Broken Hill, small Tasmanian villages like Longford, the South Sea islands and into Hawaii and the Pacific Islands.

The troop disembarked in California in March 1910, the tour had lasted nine months. Peixotto stated that it was unlikely he or anyone who had made the tour would ever experience anything as great again.

Peixotto completed a second Australian tour in 1911, amidst less fanfare, while expected reciprocal Australian tours to San Francisco never eventuated.

With Aussie Rules failing to impress American colleges, it is likely Peixotto’s 1911 visit lacked the footballing mission of the first. In 1913 his very fortunate charges enjoyed a world tour.

World War One forever halted Peixotto’s efforts to spread our code, and any further dabbling with Aussie Rules in San Francisco; something “Joker” Hall forever rued.

If Peixotto had arrived in Melbourne a year earlier, things may have been vastly different. By 1909, the AFC, the governing body of Australian Rules, had recently been hurt and humiliated by their doomed American college venture, they were bunkering down; international expansion was off their agenda, the struggling frontier outpost Aussie Rules competitions of NSW, Queensland and New Zealand, all capitulating to forms of rugby, was exhausting their expansion budget.

Con Hickey, the VFL delegate to the AFC, was in a blinkered mindset just when the Americans arrived on his doorstep. The VFL failed to embrace and properly consider Peixotto’s grand vision, and no one else since has come to these shores with such a bold vision for our game.

San Francisco was one of the very places where rugby union survived, when it all but disappeared in America, before a healthy 1960s re-birth. Australian Rules in the United States has never risen above boutique status. American football has subsequently enjoyed monumental growth.

Peixotto never established Aussie Rules in San Francisco, and the reasons for that are open to conjecture. Rugby filled a space left open when American football was dropped as a junior sport in the north-west California region.

The lesser-known Australian Rules could not match rugby for infrastructure. Perhaps if Hickey and the VFL had reciprocated Peixotto’s enormous efforts with Australian Rules, and had thrown their hat into his lot, a strong delegation could have supported San Francisco with part of the expansion budget. We will never know.

I’m with “Joker” Hall who, in the Herald in 1925, lamented: “It was a chance of a lifetime to get our great game established in America.”