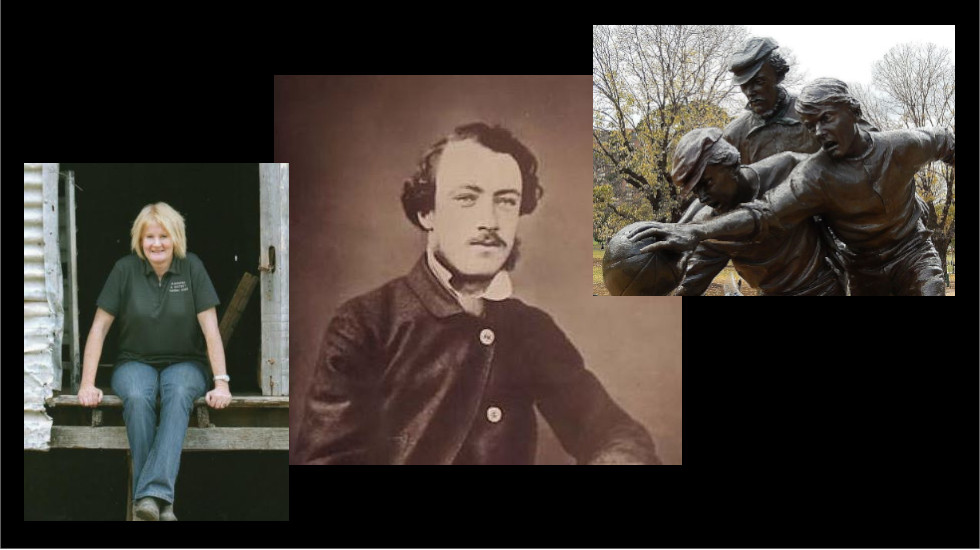

Ruth Brain (left) and Tom Wills, the “father” of Australian rules football, commemorated in this MCG statue (Wills at rear).

Moyston is green this time of year. The giant blue hump of Gariwerd, with its museum of rock art, rises to the south. The Tjapwurrung say Gariwerd is where fire fell to earth. This is a place of myths and legends.

Moyston is where a mixed-up, hopeless visionary called Tom Wills spent his childhood in the 1840s, playing with the children of the Tjapwurrung, speaking their language, using their weapons, playing their games.

Then he got sent to (of all places) the Rugby school in England. In 1856, aged 21, he returned to Melbourne dressed as a dandy with a reputation for being one of the best young cricketers in England. He revolutionised sport in the brash young colony of Victoria and was the catalyst behind the creation of the game we call Australian rules football.

His influence was felt everywhere. He co-wrote the first rules of the game, helped found Melbourne Football Club, introduced the oval-shaped ball while captaining Richmond, was three times Champion of the Colony (the original Brownlow Medal) while playing for Geelong, and introduced the tactic of playing players forward of the ball, thereby creating the idea of a forward line.

Stories imprint themselves on places. The ruins of Troy in northern Turkey summon names like Ulysses and Achilles. A bay in southern Turkey is remembered as Anzac Cove. Tom Wills is from Moyston like Bradman is from Bowral.

You can argue about that statement too, if you wish. Wills was born on the Molonglo Plains, outside what is now Canberra. But the Jesuits say give me a boy ‘til he’s seven and he’s mine for life. By that measure, Tom Wills is Moyston’s. The large red-brick house his father built still stands on the slope above the Moyston footy ground.

Every year, before the AFL grand final, I would go to the Aboriginal scarred tree on the hill between Punt Road and the MCG, then visit Tom Wills’ statue before entering the stadium. This year’s the grand final is in Queensland, but Tom is a strong story up there, only for different reasons.

In central Queensland in 1861, Tom Wills survived what is remembered as the Cullin-la-ringo massacre. It was the biggest massacre of whites by blacks in Australian history, his father among the dead. In the retributions that followed, many times more Aboriginal people died.

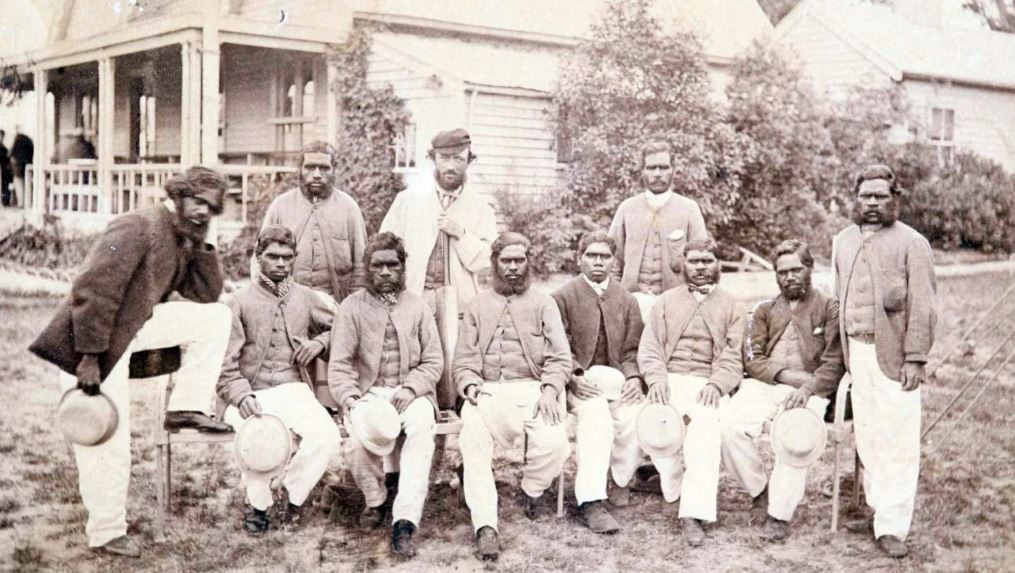

Did Tom Wills participate in those retribution raids? He may have. But within two years, he was accused by a neighbour of letting Aboriginal people back on to his land, and in 1866, five years after his father’s killing, he was coaching the Aboriginal cricket team that became the first Australian cricket team to tour England.

At the MCG on Boxing Day, a member of the team was asked if Wills was teaching them English. He replied: “Wills along (belong) us. He talk blackfella language”.

Tom Wills (back row wearing cap) with the Aboriginal cricket team in 1866.

While the Cullin-la-ringo massacre was being blamed on “the treachery of the blacks”, Wills alone blamed a neighbouring squatter who was randomly shooting Aboriginal people. Tom Wills was an Australian Hamlet, a young man with two narratives clashing in his head.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

In 1880, he died by his own hand. For 80 years he was forgotten, but he’s well and truly back now. Contentious in life, he is no less contentious in death. His critics continue to dismiss him. What they can’t do is kill him off.

Here’s another Moyston story for you. It’s about Ruth Brain, the woman who saved the local footy club after it got down to having only five at training. The first time I rang her, she said: “I’ll just take down your number”. I thought she meant with a pen on paper. She meant with a stick scratched into the dirt of the paddock she was in.

Another time I rang, she was laying concrete for a netball court. Once when I was watching a game at Moyston and she finally ran out of workers, I volunteered to goal umpire. She said: “Don’t you bugger this up!”, and I did. She leaked the story to the Ararat Advertiser along with a photo of me dressed as a goal umpire.

Ruth had studied arts at university in her early 20s, but came home because she loved the land. She was cheeky and brave, a keen golfer, a farmer’s wife, and, as she put it, the mother of three footballers and a netballer.

In 2008, she and I took on the AFL after the Moyston Willaura Football Netball Club was cut out of the AFL’s 150th year celebrations because of the politics surrounding Tom Wills, his connection with Aboriginal people, and the implications of that for the history of the game.

Ruth said Tom Wills made the Moyston Willaura Football Netball Club unique. She became the first woman president of the Mininera league. A feller from AFL Victoria told me Ruth saved footy in the place Tom Wills is from.

Each year, I go away for a weekend with a group of fellas. In 2014, Ruth rang up and wanted me to speak at a league function that weekend. I said: I’m going away with my mates. She said in that winning way of hers: “Well, I know who you’re going to have to disappoint…”

I duly drove to Moyston and sat beside Ruth at the official table. Main course was chicken or beef. She accused me of pinching her chicken when she left the table to organise trophies for the juniors.

Three weeks before at a match she’d got between two brawling ice addicts. She told me she was terrified, but she wasn’t having fighting at her games. Ruth passed away later that night. Only 52 years of age.

Five days later, Moyston Willaura won their first ever flag. I’ve seen matches played in someone’s memory before. But I’d only seen it done for men. Never for a woman and never, not ever, with such power. She wasn’t there but she was.

Moyston’s got a story that laps Australia. Tom Wills is in it. So is Ruth Brain. I never go to Moyston that I don’t see both of them.

Thanks for story on Ruth Brain. Tom Wills’ life is fascinating.