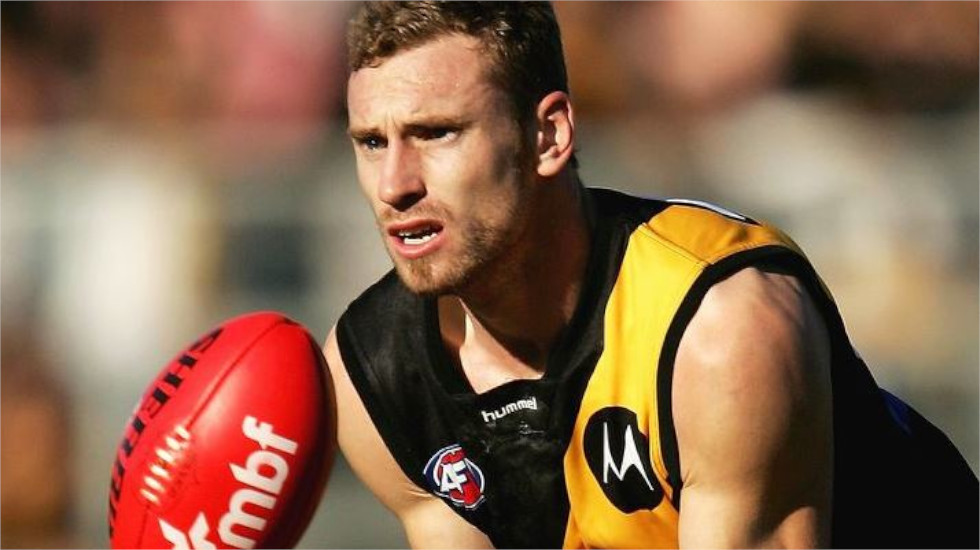

Shane Tuck, the son of football royalty, was a favourite of legendary Richmond coach coach Tom Hafey. Photo: GETTY IMAGES

Daicos, Ablett, Matera, Kennedy, Shaw, Rioli, Liberatore, Moore, Hawkins, Murphy, Silvagni, Aish. Generational names in AFL-dominant states and with it a meaningful and identifiable part of the game’s lineage and fabric.

It helps to keep us anchored to our clubs, our sense of belonging to a collective tribe, but also to the sport itself. There is recognition in name and deed, even in the age of drafts and family units being sent to all points of the compass.

After the demise of Fitzroy, former back-pocket Brian Brown’s son, a fella called Jonathan, would take the national competition by the scruff of the neck to the tune of three premierships and nigh on 600 goals for Brisbane.

Over in the west, Bryan Cousins came to the Cats in the 1970s and son Ben went on to earn a remarkable six All-Australian gongs and a flag with West Coast, while Eagles skipper Murray Rance bequeathed Alex, clad in yellow-and-black and arguably the best full-back this century has seen.

Tim Watson is a suit with a microphone to younger fans these days, but as a three-time flag winner and four-time best and fairest winner with the Dons, his record eclipses that of son Jobe, no mean slouch himself with three B&Fs and two All-Australian guernseys.

Second and third generation prominence is not confined to Australian rules football. Off the top of the head comes Archie Manning – with it Eli and Peyton – in the NFL.

Cross to the NBL and there’s Joe Bryant and son Kobe. Not often does the son upstage the father, but the example of Shaun Wright-Phillips, son of Arsenal and England striker Ian Wright, provides the counterpoint. Closer to home we have the Marsh and Healy cricket families.

But it’s not just personnel that provides the continuation. The sense of place and tradition draws us back.

Some readers will remember cursing the mud of Moorabbin, braving the primitive fortress of Victoria Park and strolling through the graceful surrounds of Princes Park. There is still grace at AFL venues; a balmy night game at the majestic Sydney Cricket Ground is a sight not to be missed, likewise drinking in the atmosphere of the magnificent Adelaide Oval.

These are where memories are made, where the greats shine. It leaves its mark.

At the age of 11, I was taken to the MCG – a two-hour drive from where we lived – to watch Melbourne play Hawthorn. It was Round 21, 1982.

There is little I recall from the game apart from the single-handed attempt by Robert Flower to drag his beloved Demons back into the game. Down by 43 points at three-quarter time, Melbourne fell 11 points short. I do remember the smallish crowd roaring its support as the Dees charged back into contention.

Flower finished with 30 touches, up against John Kennedy junior, son of John Kennedy senior and father of Josh, Geoff Ablett, uncle of Gary junior, and Michael Tuck, father of Shane.

Three decades later, I’m face to face with Shane, smiling as we try to disentangle him from beloved Tiger figure, Tommy Hafey. It was a photo shoot at Punt Road, the quirky former VFL ground that a group of country kids and their parents had walked past all those years before.

In the many conversations I had with Tommy over the years, his admiration for the way Shane bored in and gave his all stood out.

He would have liked to have coached him back in his day, he said. Tucky would fit right in, he said. It’s easy to imagine Shane charging into packs with the likes of Francis Bourke, Roger Dean, Kevin Sheedy and Tony Jewell urging him on.

It was time for the photo.

Shane nodded, grinning all the while and moved off to the side of the Punt Road change rooms. Before he went, Tommy put an arm around his shoulder and wished him well. He knew.