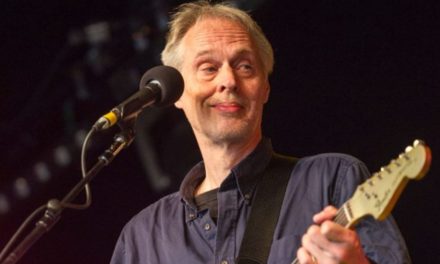

Afghan folksinger Fawad Andarabi was murdered by the Taliban recently. Picture: YouTube.

In the West, everyone can be a music critic. In Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, to be a critic is to be a murderer.

Two weeks after the Taliban took control of Kabul, they put a bullet through the head of Fawad Andarabi. He was a folksinger.

His son Jawad told Associated Press his father was killed on the family farm “shot in the head” in Baghlan province of Afghanistan.

“He was innocent, a singer who only was entertaining people,” Jawad said.

Massoud Andarabi, Afghanistan’s former Minister of Interior, spoke of the singer “who was simply bringing joy to this valley and its people.”

Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid said, “Music is forbidden in Islam, but we’re hoping that we can persuade people not to do such things, instead of pressuring them.”

That would be the pressure of a bullet entering the flesh and bone at a speed of say 2000 km/h.

That’s more than criticism. That’s barbarism.

With the taking of Kabul, the sounds of music are now fragile. The Afghanistan National Institute of Music has been closed down, radio stations have been ordered to stop playing music. The institute’s founder, Ahmad Sarmast, who now lives in Melbourne, reportedly said: “We never expected that Afghanistan will be returning to the stone age.”

When musicians and singers are in hiding, or worse, shot, then it is indeed the stone age.

The Taliban say music can only exist when it is in service to their ideology. It has no other function.

The cruel irony is that in the stone age there was music. Stone flutes have been found from the Palaeolithic era.

But one can reasonably think the Taliban aren’t big on irony, or nuance.

It follows that to still every voice requires the killing of every voice, for folk music at its most elemental is the oral tradition. It is life force. The pressuring of compliance through a bullet to the head shows the Taliban are death force.

Another irony is this: several months ago as the Americans started receding, and the Taliban began surging, the latter embraced that totem of the present – social media. They started tweeting. Guns will only get you so many likes.

This may seem an example of what the Taliban have indicated that things this time round will be different, but it makes no sense; for to change means to compromise. And the Taliban to do that would need to diminish what they are.

When they came to power in 1996, what men and women could dress was enforced, especially towards women, who were robbed of their identity. They became chattels. They could not work nor could they get an education. It remains to be seen how far their brave demonstrations get this time. If first indications are anything, not very: universities are going to be segregated by gender. Women can study but not as equals with men, and there is going to be a review of which subjects will be taught.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Public executions and the cutting off of limbs for those who breached the Taliban branch of Islamic law were common. In this society, music, television and cinema were the enemies. Mercifully their time lasted only to 2001, when the towers fell.

The problem the Taliban have to construct their hermetic kingdom is that the song will only be dead when all the singers are dead. Given their focus on elimination this may seem plausible. But it is not. It only takes one voice.

Fawad Andarabi isn’t the first folksinger to suffer at the hands of the dictator or regime. Victor Jara, a Chilean singer, writer and teacher, was tortured and murdered in 1973 during the regime of Augusto Pinochet. After the downfall of President Salvador Allende, Jara’s days were numbered. He was shot dead, like Andarabi, and his body tossed like rubbish into the streets of Santiago.

But before he died, his wrists were broken. His last song, written in Chile Stadium, contained this: “How hard it is to sing when I must sing of horror/ Horror which I am living, horror which I am dying.”

Three years later, Australian singer Jeannie Lewis covered Jara’s song Chile Stadium on her album Tears of Steel and the Clowning Calaveras.

Last year Roger Waters covered Jara’s The Right to Live in Peace. Releasing it, he said: “This is for the people of Santiago & Quito & Jaffa & Rio & La Paz & New York & Baghdad & Budapest and everywhere else the man means us harm.”

Everywhere, like in Afghanistan.

The power of song is famously illustrated many times using the example of Woody Guthrie. On his guitar were the words: This machine kills fascists. In the McCarthy era in America, Guthrie and other folk performers such as Pete Seeger and the Weavers were persecuted for their art. America was not alone in this; many countries have sought to silence their singers.

Guitar player extraordinaire and activist Tom Morello, of Rage Against the Machine and Audioslave, has updated the message. On his guitar are the words: Arm the Homeless. Bruce Springsteen and his version of The Ghost of Tom Joad is electrifying in music and message.

And Rage Against the Machine’s cover version of that tune is just as powerful.

The power of the song, however, resides in the chain of humanity. Each person is a link. Unless tyrants, and the murderous likes of the Taliban, can eliminate every single person then the song remains – as breath in a stone flute, as voice in the clear air.