For every ‘cleanskin’ champion in sport there is always another deeply flawed one to offset them.

For Roger Federer there’s John McEnroe, for Jason Dunstall there’s Gary Ablett Snr, for Royce Hart there’s Wayne Carey and for Barry Cable there’s Jimmy Krakouer.

As a kid growing up in WA I was blessed to watch some of the greatest Indigenous footballers from Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer and Bill Dempsey, through to the Riolis, Sebastian and Maurice, and onto another dynamic trio at South Fremantle in Benny Vigona, Basil Campbell and Stephen Michael.

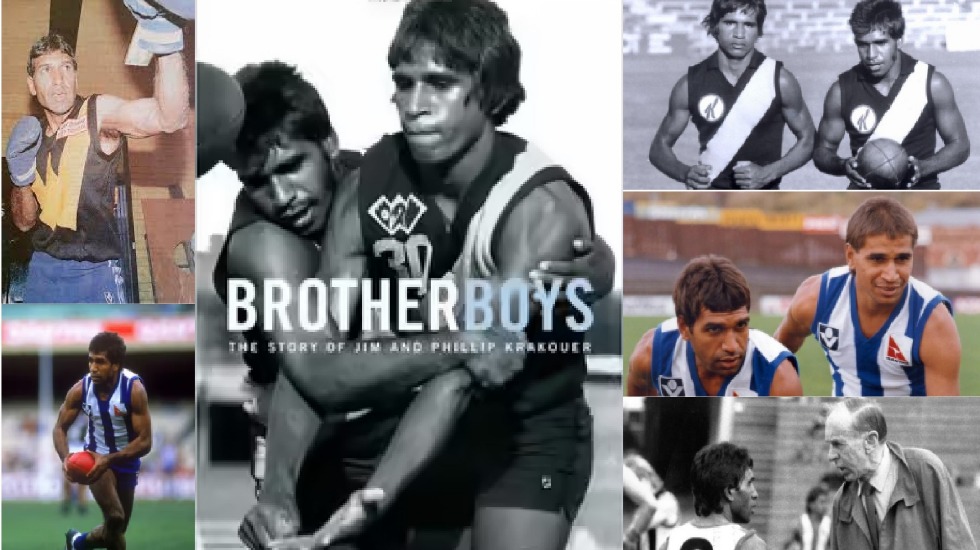

Still, nothing could compare to the sublime brilliance of Jim and Phil Krakouer at Claremont.

It’s rare that one athlete, let alone two, can enter a competition and redefine how the game would be played.

This wasn’t a Walter Lindrum-like scenario where the rules had to be changed, but certainly WAFL and VFL coaches soon had their hands full trying to contain them.

What was referred to as ‘Krakouer Magic’ by the media and fans didn’t come from some mystical bolt of lightning but from thousands of hours practicing as kids growing up in the tiny town of Mount Barker in WA.

Living in a small home as part of a family of 11 children in a shanty Aboriginal community on the outskirts of town, no one could blame the boys for spending the bulk of their time outdoors with a footy. It led to them both having exquisite skills and an almost supernatural connection on the field.

Brought to Perth by Claremont, the teenage brothers soon dominated and played for their state as well as playing a major role in the 1981 WAFL premiership. So impressive were they that North Melbourne signed them in 1980 for the start of the 1982 VFL season.

In what would be a rollercoaster eight years at North, the brothers mesmerised with their skill and pace but had numerous injuries and, in Jim’s case, anger management issues.

All up, Jim missed an entire season in his career suspended. Given he was 5’6” tall and 65kg dripping wet, how was it possible this man terrified the hardest of opposition players?

From actual conversations with childhood friends in Sean Gorman’s book Brother Boys, it’s apparent Jim was always a powder keg prone to spontaneous acts of violence. Many of these acts were exacerbated by bullies and racial discrimination, however by all accounts Jim could be highly unpredictable.

This was the opposite to Phil who was much more laidback and very similar in temperament to the few Indigenous players that had come before them in the VFL. Sir Doug Nicholls, Syd Jackson, Farmer and Cable were men who suffered enormous vilification in their careers and used it to make them stronger rather than retaliate.

For Jim this was never the case. If you chose to go down the path of racial abuse, if you were responsible for hurting Phil or if you were going to restrain him from accessing the ball illegally, you could expect a left hook – not negotiable. And this continued despite all the counselling from coaching giant John Kennedy and mentor Ron Joseph.

In 1993 Jim entered the changerooms at Werribee in the VFA and for me, it was like Elvis had entered the building. A good friend of coach Donald McDonald and former teammate of our fullback Tim Harrington at North Melbourne, Jim had joined his brother Billy at Werribee after being retired for a year.

It took approximately six weeks to get him fit enough to play and his one and only game was against our arch enemy Williamstown at their ground, Point Gellibrand.

A big crowd turned out to see the diminutive legend play and as if sensing the theatre, Williamstown coach Barry Round decided to tag Jim with a dour, uncompromising defender Tom McGowan.

I’m pretty sure it was the first quarter and I was doing my best concentrating on my opponent in the centre, VFA champion Billy Swan, when suddenly I heard that noise we all hate – fist on face. The only grandstand at Point Gellibrand exploded into a cacophony of venomous abuse and histrionics the likes of which I’d never heard or seen before.

McGowan was semiconscious, bleeding and prostrate on his back as dozens of Williamstown players charged at Jim whilst hapless Werribee players including myself stood between him and the encroaching vengeful hoards.

McGowan had been warned twice by Jim not to hold his jumper when he tried to run. Clearly, he hadn’t read the rulebook according to Jimmy, and paid the price.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

I remember vividly walking off at half-time, myself and another teammate with our arms around Jim as the crowd rushed the visitors’ race. We were spat on and Jim was exposed to the most disgusting vitriol imaginable.

It’s one thing to be upset and vent your anger regarding an action that has taken place on the field, but every obscenity that was delivered to Jim that day had the prefix ‘black’ attached to it. It was a small but stark reality as to what the great Indigenous players had to deal with over the decades.

Ironically it was the same year that St Kilda’s Nicky Winmar took a brave and defiant stand against a maniacal Collingwood crowd at Victoria Park, now immortalised in bronze out the front of Perth’s Optus Stadium.

Less than a year later Jim tried to transport $500,000 worth of amphetamines across the Nullarbor and was busted. Originally sentenced to 16 years, he served nine.

For such a shy man, Jim definitely carried a chip on his shoulder. That chip reduced his appearances for North to 134 games and caused considerable stress off the field by making poor choices.

Brother Boys is well researched given Sean wrote it as part of a PhD and it doesn’t hide from the ugly side of Jim’s life. Trauma came early with an alleged rape when he was 16 and accidentally hitting and killing a road worker whilst recklessly driving as a 17-year-old. Then there was his conviction on sexual assault charges with a minor in Melbourne in 1985.

All of these actions are unforgivable. Regardless of what happened, they amount to poor decisions. Ultimately the drug trafficking was the nail in the coffin.

I had mixed feelings reading these accounts but I was pleased that Jim was able to openly share his stories with Sean during the numerous visits to gaol.

From the appearances since his release from gaol he seems happy and was inducted into North Melbourne’s Hall of Fame in 2016 and the WAFL Hall of Fame in 2021. Jim is also in North Melbourne’s Team of the Century and the Australian Indigenous Team of the Century.

There are former teammates and officials at North that put Jim in the top five players to ever walk into Arden Street. It’s a huge call when you consider the past champions at the club, but according to McDonald and Harrington, he was the toughest player they had ever seen and given his size, makes it all the more remarkable.

For me as a fan he was the best ‘front-and-square’ player of all time. As a coach you teach mere mortals to approach a contest ‘front and square’, but slow down and ‘mark time’ so as not to go past the contest. Jim would hit the contest like a bullet, anticipating the drop and with impeccably clean hands, gather and explode away.

Without Phil, there would have been no Jim. Whereas Jim simply ran through obstructions at speed, Phil was the rubbery master of evasion and incredibly skilful. This is a lovely summation of the brothers after a match from the Melbourne media:

There are athletes in every sport who defy the limitations which both nature and the rules of their sport impose on them. To watch them perform is, in the true sense of the word, a transcendental experience for they push back the boundaries of what we believe is possible. They set the outer limits. Both of them are blessed with a special grace and the sort of natural instincts and skills possessed by no other footballers in Australia today. They are the Pele and Maradona of the VFL.

Gifted footballers with behavioural issues have always had a level of protection offered to them that has never existed for the average player. Perhaps Jim had his share but certainly much of his transgressing can be traced back to his upbringing. He had a loving family but he was always a risk taker and seemingly forever on edge.

It took me way too long to finally read Brother Boys as it was published in 2005. If you marvelled at the extraordinary chemistry of the Krakouers, this is a terrific read. It’s a story worthy of a film and thankfully it ends with redemption.

This is a short video of Jim and Phil’s work. Check out the torpedo-on-the-run goal he kicks against Essendon. One of many, “Did you see that?” moments Jim and Phil provided in their careers.

*You can read more of Ian Wilson’s work at WWW.ISOWILSON.COM