McAvaney’s style carried the biggest moments in the biggest games. And Bruce had a way of conducting those big moments.

As the Bruce McAvaney tributes roll in, it can’t be underestimated just how central a role he played in the evolution of Friday as footy’s night.

Bruce McAvaney was a man for the times. As the VFL became the AFL in 1990, McAvaney joined the Channel 7 broadcast team. A national outlook was required, and a South Australian who had gained a national profile through his work on the Olympics in 1984 and 1988 in retrospect seems a masterstroke as a subtle shift from the old VFL.

While endlessly parodied (usually in an affectionate way) for it, his preparation and encyclopaedic knowledge of whatever he was covering was a more obvious shift.

It was an unashamed move to value accuracy, statistical information and background knowledge rather than the knockabout ex-player commentary that was still prevalent. It was, shock horror, a little bit intellectual.

It was usually urbane, and consistent with his Olympic experience, had the international touch about it. At the time it was only really common with his later-career Friday night partner Dennis Cometti

But as the ‘90s started, Friday night was not the crown jewel that it would become. Long before it headlined eye-watering television rights deals that essentially delivered on the promises of national expansion, it was a decade-long experiment.

Despite its debut in 1985, as late as 1992, only 15 of the 24 rounds featured a Friday night game. Five of those games drew less than 10,000 fans, and its season average of under 23,000 was only propped up by one crowd of 88,000 for a Collingwood Essendon clash.

More telling was that Friday night games in Melbourne were still being played in a truncated highlight package form at 9:30pm on local television. The game was effectively over by the time it came on air. Most cold Friday night in Melbourne featured the then-lowly North Melbourne and often low drawing teams from interstate. It was far from the event it would soon become.

A string of classic Friday night games in 1993 certainly gave the concept the kick-along it needed, and by then McAvaney through his mix of knowledge, calling ability and freshness had clearly ascended to the top dog in the Channel 7 box.

But 1993’s Friday night revival did not translate initially. In the following season, again only 15 of the 24 rounds featured a Friday night game, and still Melbourne games were in late highlight form.

But by then it was clearly identified that McAvaney’s style, that was becoming more expressive by the year, was carrying the biggest moments in the biggest games. And for the growing crowds on Friday night, Bruce had a way of conducting those big moments.

The true making of Friday Night Footy came in 1995, and from this day onwards, Bruce owned the slot.

The decision was made to broadcast a full game replay “as live” from 8:30pm on Friday nights. Which brought in that ‘90s football-watching curiosity of staying away from the radio until 8:30pm to savour a live experience – something that the vast majority of fans did.

McAvaney was teamed every week with Ian Robertson and Gerard Healy that season, and a good chemistry developed of McAvaney as the virtuoso, the meat-and-potatoes caller (Robertson) and the most youthful of the expert comments men who could give fresher analysis then others.

Momentum for Fridays grew week on week with a few helpful factors. A Richmond revival in 1995 that had its key moments play out on Friday night was one part, but there was a broader factor at play that McAvaney could claim a bigger influence upon.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

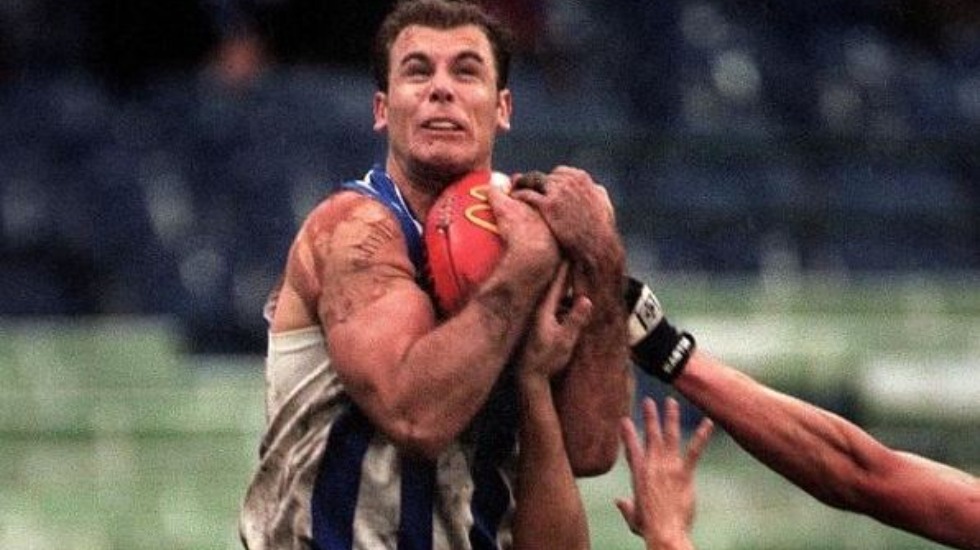

North Melbourne was now the emerging force of the league, heading to the second of seven straight preliminary final appearances. And whatever your opinion of the guy is now, in 1995, Wayne Carey was the best player and best box office draw in the game.

Carey to McAvaney on a Friday night was footy’s answer to the Muhammad Ali-Howard Cosell broadcasting muse, each other’s careers lifting the other.

Healy and McAvaney termed and popularised the “King” Carey moniker, and in the process something akin to an Australian Ali or Michael Jordan was being created. A narrative was being weaved that footy was at its best with Carey on Friday nights, and how could anyone argue with McAvaney’s precision passion.

Carey to McAvaney was footy’s answer to the Muhammad Ali-Howard Cosell broadcasting muse, each other’s careers lifting the other.

The great worry of broadcasting close to live was that crowds would drop, but the reverse was true. Once people were exposed to marquee matches on Friday night television, with the drama orchestrated by the natural enthusiasm built on ultimate preparation and professionalism of a genuine sports lover like McAvaney, they started attending too. The more people that went to matches, the more people tuned in.

Friday night crowds at the MCG jumped from an average of less than 25,000 in 1992 to just under 45,000 in 1995 despite them now being broadcast “as live”.

The fact the Kangaroos had smallest supporter base among Melbourne clubs only strengthened the cultural shift. People watched in droves not because they barracked for North Melbourne, but because they wanted to see the best game of the weekend. They used that quaint term “theatregoers” in the era, and McAvaney was the director.

Midway through 1995, Seven’s football ratings had already jumped substantially on the previous year, fuelled by Friday night. After 726,000 people had tuned in to watch the season’s eventual premiers take on the previous season’s wooden spooners, station executive Gary Fenton gave “The Age” some clues of the cultural change.

“We’ve seen the evolution of the AFL follower, in Melbourne in particular, where he has a team he barracks for, but he’s become a very broad-based AFL follower,” Fenton said. “He watches the game when his own team’s not participating. And that’s understandable … it’s a more entertaining game. Its good television.”

Starting in 1995, it quickly became a ritual to spend Friday nights with Bruce, who was, as Fenton put it, the ultimate “AFL follower” – no known club allegiance, and enthusiasm for every great player.

In a big year, the flagship “Talking Footy” program also started, which was effectively the first rigorous analytical look at the game and its politics, with McAvaney at the helm. It was a critical hit and essentially laid the platform for any football analysis onwards.

It was the credible seal of approval that confirmed him as the voice of footy and confirmed a new sophistication for fans to appreciate the game beyond their allegiances – the whole bedrock of attracting fans of all stripes on Friday nights. Again, McAvaney was a man for the times.

Aside from years that Channel 9 owned Fridays, Bruce has been the constant since this evolution.

It’s true that ‘90s Bruce was better than more recent Bruce, which is not to stay his stature or skills had diminished sharply. It’s just that like your favourite band, you’ll always treasure the era when they first scaled the mountain, and that was Friday night in the ‘90s.

It is a shame that there is not a farewell tour for tributes to be paid, but this has never been McAvaney’s style. Over the last 20 years, he’s gradually receded from his 1990s omnipresence, and the true nature of his ego-free performance has become clear. It makes his body of work even more likable.

When you heard Bruce open a broadcast you knew that it was the main event of the weekend. Perhaps even more than North Melbourne’s famous number 18, he has been the most iconic figure of the Friday night football phenomenon.

Lovely article. Though the recent years of the eternal rhetorical question has been less than those of an earlier era, Bruce McAvaney’s voice always heralds an intelligent and knowledgeable commentary. Unlike so many others…,.