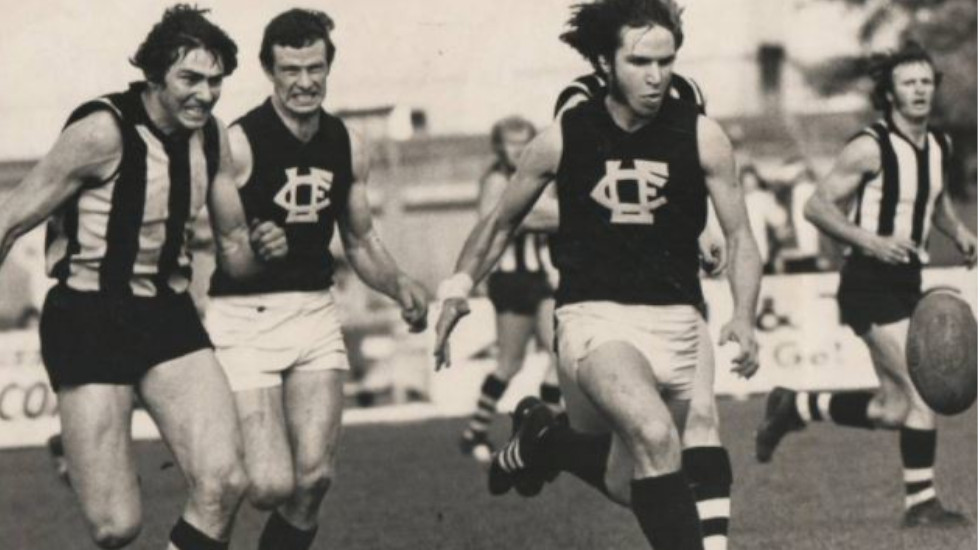

Scottsdale’s Danny Hall (far left): Like Dermott Brereton, a very good player, and like Brereton, scary. Photo: THE EXAMINER

Built on a swamp between two rivers, Invermay flooded every decade or so from the time of first settlement.

People from Invermay, the toughest part of town, were called “Swampies”. Their football club was North Launceston. Foo and I meet at 27 Burns Street Invermay, the ancestral seat of our clan. I tell him some footy stories about my grandfather, his great-great-grandfather, as we walk to the ground.

We’re going to see North play Launceston at York Park. North Launceston was born in 1893, one year after Collingwood and for much the same reasons.

Launceston, the oldest football club in Tasmania (1875), has a touch of Melbourne Football Club about it, having traditionally drawn from a different class. Footy was where I learnt about class politics growing up. You learnt or you lost your head next time you played them.

Over the years, North Launceston has played with the imperious working class arrogance patented by Collingwood in the 1920s.

Back when I covered northern Tasmanian footy in the early ‘80s, there was a team that matched North in what was called the rough stuff. A country team called Scottsdale. They had a player called Danny Hall, who shared certain qualities with Dermott Brereton. Like Brereton, he was a very good player. Like Brereton, he was scary. I saw Danny Hall take on North singlehandedly one day. It was like a Clint Eastwood movie.

As we make our way through the back streets of Invermay, I tell Foo about the old Irishman I met in Elphin, County Roscommon, where Flanagans have lived for the past thousand years, who declared to me: “Flanagans are interested in four things – football, politics, horses and cattle”. I’ve got two of the four, Foo’s got three – that makes us a Venn diagram of sorts.

Foo reminds me of his grandfather, Jeff. He has the same eagerness to engage when a good story’s in the offing. Most of Jeff’s stories were about his father, Tom.

A big character, my uncle Tom reminds me of my brother, Richard. He’s Foo’s great-great grandfather. The point I make to Foo is that my great-great-grandfather is Thomas Flanagan the convict from Elphin, County Roscommon, who was transported here in 1847. Not only are we descended from him, so is former Collingwood champion Dane Swan.

I once wrote about this connection in “The Age” newspaper. I ran into “Swannie” a year or two later. All he said was: “amazing how people think you are a better player once they think they’re family.”

It’s true. After I knew we shared a convict ancestor, I stopped asking myself how “Swannie” did it when he was the wrong build, his legs were too short and he shuffled rather than ran, and just gloried in the fact that he did.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Foo’s bought tickets which take us into York Park via Mowbray Cricket Ground. Ricky Ponting’s cricket club. Foo’s club. As an opening batsman, Foo (real name Mathew Adams) played two games with Ricky when Ponting was one of the three best batsmen in the world. “Punter” never forgot where he was from. It may not sound like much, but in terms of nurturing sports and keeping them alive, it’s huge.

As is the habit of Mowbray cricketers, Ponting played footy for North Launceston and, from what I’ve heard, played in what is called “the North Launceston way”.

Skilful and hard and more than capable if and when it came to the rough stuff. Foo played under 18s with North, but played his senior football in the bush, kicking a lot of goals as an undersized forward. Ended up coaching Evandale.

It’s 7 o’clock at night and getting cold. We are crossing Mowbray cricket ground when I look up and am hit in both eyeballs by what looks like a giant black shape bursting with white light. That’s my first shock. York Park is not York Park anymore. It’s an AFL stadium, a football fantasyland of a new and brilliantly lit variety.

I’ve lots of memories of the old York Park and struggle to house them. I’m like a bird flying back and finding its forest gone. Meanwhile, the game is ferocious. North have won six of the last seven state titles, but Launceston beat them last time they met, at Launceston’s home ground. York Park, UTAS Stadium, call it what you will, is in Invermay. It was built on the swamp. It’s North Launceston’s home ground, always has been.

North’s team looks like 15 middle weight boxers with a couple of squat heavyweights thrown in. They are bigger, stronger, more finely tuned than the players I saw in the ‘80s, but there is a uniformity about the way they play, just as there was a uniformity about the way North Launceston played when I saw them 40 years ago.

That’s my second shock. America is disintegrating, the polar icecaps are melting, the world is giddy with change – but North Launceston is still North Launceston.

I’m the old fool babbling on the boundary, telling Foo all this, but the truth is I’ve come to watch one player in particular, North Launceston’s Josh Ponting, twice winner of the Alastair Lynch medal for the best player in the Tasmania Statewide League, and another of Jeff Flanagan’s grandsons.

I study him like I used to study Dane Swan. He reminds me of former North Melbourne player Brady Rawlings (another Tassie boy) – wiry, hard-running, diligent, in and under, quick and clever with his hands. A thinking footballer. His Nan, Rayma, watches admiringly from behind glass. Once she stood by the gate whacking every North player on the bum as they ran out on to the field of play.

It’s a match with real pride at stake, the two best teams in Tasmania. It deserves a much bigger audience.

Not only is North Launceston still North Launceston, Launceston is still Launceston. They’ve got more individual style, are better to watch and come off second best but are close enough at the end to think maybe better luck next time. My legs are semi frozen by that stage and have to be cranked into motion. Foo runs me home. Since then I’ve thought of more stories I want to tell him.

No mention of the 1976 NTFA Grand Final, the 1985 Beer Wars NTFA Grand Final or the latest 2020 TFL Grand Final. Go Blue Boys!

Why does this bloke never mention that glorious defeat of the Map amateurs at the hands of Country Vic’s in 1975 when we kicked the best score ever, albeit the usual thrashing?