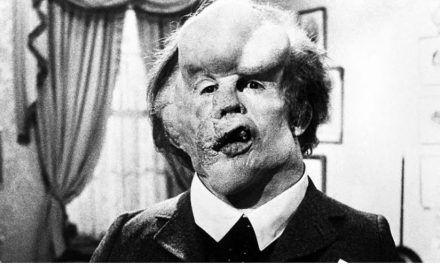

(Main image): Dustin Martin changing the game just before half-time. (Inset): Nick Vlastuin (left); Gary Ablett and son Levi.

The morning after the Grand Final, I woke knowing I’d seen something special, but not sure what. I rang former Hawthorn coach Peter Schwab. He said the game was like a title fight that was ended in the 13th round on a TKO. It didn’t go the distance – a measure of the great fights – but it was still memorable.

Lots of Grand Finals disappoint. This one didn’t. Afterwards, I wanted to see a replay of the game, which I hadn’t after Richmond’s previous two premierships.

One of the ways I judge a game is by the number of visual images it crams into my head, like photographs to be taken out at a later date and examined – eg. Dustin Martin’s goal just before half-time.

The flow of any game is like the current of a river and at that point it was pulling strongly away from the Tigers, taking their destiny with it. “Dusty” took the ball high, it bobbled in his grasp and he had to invent his kick in mid-air, beating off a tackle as he did.

Degree of virtuosity? Extremely high. Then he wheeled away, eyes ablaze, grabbed his Richmond guernsey and put it to his teammates. It was a different game after that.

I’d love to get a Maori perspective on Dusty Martin. I got a Maori perspective on Lionel Rose, the former world champion boxer, after his funeral service at Festival Hall in 2011.

Rose was the 20-year-old Aboriginal kid from Gippsland who won the world title in Tokyo in 1968 against the best boxer Japan had ever produced, Fighting Harada. I attended his funeral with my cousin Arthur Kemp, an old boxer and a mate of Lionel’s.

As Lionel’s coffin passed us in a hearse, a Maori standing beside us erupted into a haka. The air blurred as the whole of his being reverberated in a profound gesture of respect, a warrior’s farewell.

I spent the Friday before the 2017 grand final wandering round the old inner-city working class suburb of Richmond, sucking in the vibes. I came around a corner in Alfred Street to find a crowd of maybe 200 people standing, not talking, not moving. It was like visiting a religious shrine at Lourdes. They were looking at a mural of Dusty, this young man who is knowable but unknowable, who is both insider and outsider.

I saw a quote from Dusty where he said he didn’t understand why people are interested in him, he’s just an ordinary person. No doubt this is true.

What’s extraordinary about him is his aura, which is as big as exists in our game. Actors like Marilyn Monroe and James Dean had auras – both expressed something about their eras, something previously hidden or unspoken.

With his many tattoos and shaved head, Dusty could easily be demonised – as nearly happened after an incident in a restaurant in 2016 – but as club president Peggy O’Neal said at the time, he is not a violent man.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

The most arresting line I read about Dusty after this year’s Grand Final was an eight-word tweet written by a Tamil migrant, Marcella Brassett: “Dusty Martin is a wild god among men”.

Hawthorn’s “Lethal” Leigh Matthews is commonly cited as the best player of all time. Like Dusty, Lethal was muscular, quick and confident. Matthews played in a more violent era and fought fire with fire, even starting fires on a couple of famous occasions.

Dusty plays without malice. Peter Schwab played with Matthews. I asked him – if you rated Leigh Matthews as a footballer as a 10, how many would you give Dusty Martin? Nine-and-a half, he replied. He points out that Matthews kicked nearly 1000 goals.

I was barracking for Geelong, but was happy for Richmond to win. I applaud the Tigers as a club.

We live in a world where so many things are not working as they should. Trump is trashing the United States. Brexit has delivered Britain to a clique of privately-educated 18th century Tories. Here, the “sports rorts” affair tells you everything you need to know about the hypocrisy of the Morrison government. We need to see something that works.

Richmond Football Club works. It’s the understanding between captain, coach, president and chief executive which makes it possible for someone like Dusty Martin, who might otherwise be seen as an outsider, to thrive.

It’s also a club that has made a winning formula from diversity – Bachar Houli, the Muslim Tiger, is now a major figure in the game. Richmond is the New Zealand of football clubs.

Two other images from the night. I like Nick Vlastuin as a footballer. He has balance, mental and physical. There was a shock that followed him being knocked out in the seventh minute, particularly as Gary Ablett went down immediately after him.

The game was being played at Grand Final tempo, hard and fast. The slippery ground meant the element of risk for the players was even higher than usual. Vlastuin was back on the bench by quarter time, but the night was over for him.

A grand sporting adventure was unfolding before his eyes and he wasn’t part of it, not any more. A teammate ran over to him to comfort him. He looked up, grinned and winked. I can read winks. This one said: “I’m good. This isn’t about me, it’s about you, because you’re still in the game and I’m not.” Exceptional teams can communicate on that level.

The last image in my head is of Gary Ablett junior. What a wonderful footballer he has been. At his best, he literally did waltz past opponents, turning right, turning left, finding gaps at unexpected angles, ahead of the game in thought and deed, capable of scoring from 50 metres out on both feet and at any angle.

I saw the 1989 Grand Final, I know the legend of his father. But I got more pleasure watching the son. He was so good so often. For a decade or more, he performed with the regularity of a Japanese train.

Had he been party to getting Geelong across the line in last Saturday’s game – even, better still, had he been critical to such a result – it would have made for an aura that compared to the one that now surrounds Dusty. But it didn’t happen. Sport’s like that. Injured early, he played in pain, couldn’t do much.

After the match, there was a shot of him meeting his seriously ill infant son. He’d just played a Grand Final in which history beckoned, the whole mythology of the sport had been upon him, but at this moment that counted for nothing as his face was transformed by a father’s love and his joy at seeing his son.

Great game and a fine article.

I’m not a Richmond fan, but one has to admire how they play.

Neither was I Dusty fan – something to do with the don’t argue and he looks like a dirty player, though he’s not.

But after that game when he kicked not one but four incredible goals, how could I not admire the skill and will to win.

I might be turning into a Dusty fan.

I can only say one thing about this article by Martin Flanagan – Brilliant!

Thank you Martin, what A wonderful story that was to read enjoyed every word, THANK YOU

Please write more regularly, Martin. You are the g

Doyen of AFL journalists.

Loved the Martin Flanagan footy story keep up the great stories this was sent to me by my daughter in western Australia cheers

I can definitely appreciate your applauding Richmond as a club. I barrack for the Cats and am married into a Tigers family with most of us based in Perth. Fortunately, we have a mutual admiration for our respective sides to the point where it never becomes spiteful.

That said, I insisted on watching the game alone and while pleased that it was a rare opportunity for both sides to equal the epic status of one of our more treasured meetings, the 1967 decider, this was always going to be a battle of wills and attrition and so it was. There was not a single moment of respite and by quarter time it was getting to the point of nausea which I’d never experienced watching any game. It wasn’t pretty to watch in the sense that ’67 was but it was unforgettable just the same.

I’m repeating myself here but as I mentioned on Rohan Connolly’s take, this was in way like watching 1992 all over again. The physicality and pressure of the opening term, the false dawn (and momentum-shifting late goal) of the second, Martin’s coming to the fore in the third and, in the end, the realisation that this was most likely inevitable from the outset.

Geelong were by no means humiliated and gave as best they could but one sensed that they had to depend a little too much on Richmond making mistakes. They didn’t make too many.

I’m yet to watch a replay. It comes easy with the other grand final losses as any footy beats none at all. This one might take a while.

But again, I’m glad this happened against Richmond. They’re a side to admire and even more so with the grace they displayed in victory.

Great Article Martin is the Polly Farmer of journalism