Essendon and Port Adelaide: Weight of contemporary expectations have had very different impacts on two proud clubs.

An AFL club board member walked into a public servant’s office recently asking for approval on a stalled development application filed by his club at a city council office.

“Do you know who we are?” the director said after it became clear there would be no simple rubber-stamp endorsement at City Hall.

The sense of entitlement was not a one-off moment for this club. The public servant was not moved – although he has a great story to tell at dinner parties.

The recent attempt by Victorian-based family members of 11 Port Adelaide players to gain exemptions on entering South Australia across the closed border – to watch AFL finals at Adelaide Oval – reaffirms how AFL clubs and associates can appear out of touch with the real world.

This example – which the club says it did not engineer – was more unpalatable on noting the story of a young woman, based in Melbourne, who could not return to Adelaide to support her terminally ill, hospital-bound mother, and her father who was home alone suffering from Parkinson disease.

No surprise then that the SA chief public health officer Nicola Spurrier revoked the exemptions that were originally granted to allow access to AFL finals at Adelaide Oval.

Sport around the world is not short of the “entitled ones” – some living off past glories for far too long.

Tiger Woods knows how his hubris while living the high life as the world’s greatest golfer ruined him. “I felt I had worked hard my entire life and deserved to enjoy all the temptations around me. I felt I was entitled,” he said.

In team sports, to quote one American college sports coach, “enlightenment in sports has been replaced by entitlement”. Self-confidence becomes arrogance … a false reality where a team is entitled to everything.

In the United Kingdom, the Premier League football competition has notable examples. The Financial Times in 2006 published a research paper that revealed 90 per cent of Chelsea fans did not support the “Pensioners” in 2003 before Russian Roman Abramovich bought the London-based club from Ken Bates.

There was the note from this paper that “Chelsea fans go to (the club’s home ground) Stamford Bridge to be seen, rather than to see an actual match.”

Anyone want to draw a comparison with an AFL club?

In the United States, the sense of entitlement – a belief in deserving more than a team has earned – is noted in all professional sports. In basketball, the New York Knicks have not won any title since they claimed the division crown in 2012-13, but the history of one of the NBA’s founding clubs weighs heavily in a city of ultra-loud sporting fans.

In football, the Dallas Cowboys remain “America’s Team” – a tag they inherited in 1978 – while having no Super Bowl appearance since 1995 … but everything is always bigger in Texas.

In baseball, there are those New York Yankees – ultra-successful winner (27 World Series titles) in the 20th century but with just one crown (2009) this century (and two World Series losses). Still, as the Bleacher Report comments: “Yankee fans continue to think they are entitled to buy a championship and with this power have become so obnoxious that their egos have exponentially grown to outrageous proportions.”

In Australia, in the brash city of Sydney, the NRL has its Roosters, loaded since 1993 with the power of cash from club chairman Nick Politis, who is known as “one of the most powerful, influential and ruthless figures in rugby league … the ‘Godfather’.”

His capacity to claim star players from rival clubs such as James Tedesco from the West Tigers and Luke Keary from South Sydney has help deliver the past two NRL titles to the Roosters – and have the eastern suburbs club overtake Manly on the “entitled” pedestal.

In Brisbane, the Broncos – now fallen emperors in a monopoly NRL market – have lived like kings with cash and power in the Queensland capital, in the same way that a big AFL club thought it was entitled to override development regulations on public land.

Entitlement – by power, money or history, sometimes all three.

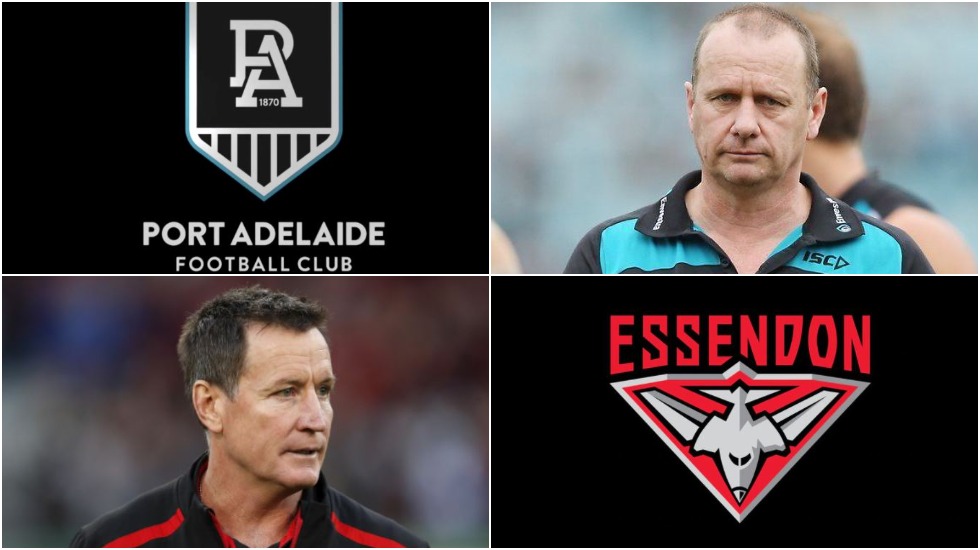

The tone of entitlement – and the burden it places on a team – was highlighted by now-departed Essendon coach John Worsfold in his last match-day press conference at Adelaide Oval in round 17.

Much – in some quarters, too much – has been made of Worsfold saying: “I understand that Essendon people think that Essendon should do better.

“But they have also got to understand that the competition challenges clubs now to work to the same rules, so the same rules at the draft and the salary cap. And no one team has any more right to be successful quicker than any other team just because they’re a big-name club.

“You have got to knuckle down and commit to doing the work. And good clubs will do that and come out of it with success.”

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Essendon has not won an AFL premiership since its near-invincible season in 2000, when it joined Carlton at the top of the VFL-AFL premiership tally. The Melbourne-based club is not only in its longest premiership drought (20 years exceeding the 19 endured between 1965 and 1984) but also has not won a final since the 2004 elimination final against Melbourne.

Collingwood president Eddie McGuire, who will claim he wore a “media hat” when he commented, described Worsfold’s summary as dropping “a bomb” on his exit from the Bombers. No surprise then that Worsfold made way for his successor Ben Rutten at the post-match media conference after the round 18 finale.

Referring to “Essendon people” rather than the “we” was a mistake by Worsfold, the West Coast premiership captain and coach. But what of the theme of his message?

Worsfold was reading from the well-worn AFL strategy sheet detailing the league administration’s intent to avoid its competition becoming the mirror image of money-driven sporting competitions, such as any big football league in Europe, where the top-six teams repeatedly play musical chairs.

But, as Worsfold proved, AFL fans do not want to hear of their dreams being hemmed by salary caps and drafts. They want their clubs to be ambitious. They will not stomach the thought of their celebrations having to wait like a patient ox doing time on Michael Malthouse’s premiership clock.

Ken Hinkley arrived at a broken Port Adelaide at the end of 2012 to face the same script lived by Worsfold at Essendon – and a frustrated supporter base that booked parties on the last Saturday in September in the same way everyone plans for Christmas.

Despite being on the edge of a cliff with its AFL licence at risk, Port Adelaide fans still expected their club – as it had done in the SANFL – to be a constant challenger for the AFL premiership. A grand final every second year in the SANFL was achieved with the biggest supporter base in pre-AFL South Australian football – and before salary caps.

No reason to lower the bar in the AFL.

Port Adelaide notably changed its “language” during the off-season. Rather than speak of competing to claim a top-eight finals berth (for the first time since 2017), the objective for season 2020 boldly became the premiership.

Hinkley’s words in February mark a strong contrast to Worsfold at Essendon: “I love this club and I love the history of this club – and this club’s history is premierships.”

Since 1870, that history is 36 SANFL flags; four Champions of Australia titles before World War I when the SA and Victorian league premiers would have an end-of-season play-off, generally in Adelaide, and one AFL title in 2004.

Port Adelaide, like Essendon, is enduring its longest premiership drought (both in the AFL and SANFL, where it could not participate this year because of COVID protocols).

“We’re going to start this year,” added Hinkley, “wanting to win the premiership in our 150th year. We’re going to do everything we can do … we’re coming.”

Hinkley spoke in the very way Port Adelaide’s traditional supporters – those who felt they “owned” the SANFL premiership – want their coach to talk, without the “excuses” that dynasties are not possible in the AFL while clubs have to work to the limitations of salary caps, drafts and every other equalisation lever the league executives pull.

And Port Adelaide has delivered on the field with the AFL minor premiership in the most-demanding circumstances.

Worsfold spoke in a tone that would be considered defeatist by an Essendon supporter base that became accustomed to success in the Kevin Sheedy era (1981-2007, four premierships – 1984, 1985, 1993 and 2000 – from seven grand finals). But pragmatic coaches are never popular among cheer squads wanting to hear how their team will win – and not why the system will not allow it.

This leaves the question: Who are the entitled ones in the AFL?

Does the AFL Commission really tremble at the prospect of agitating Collingwood president Eddie McGuire, who can mobilise the largest – and most emotional – supporter base in Australian football?

Are the modern “franchises” such as Adelaide and West Coast, with their money, corporate backing and images as “symbols of state pride”, more than just football clubs? Certainly, in Adelaide the Crows senior coach can have more influence on the emotions of South Australians (even those who do not barrack for the Crows) than the state Premier.

And does a former state Premier such as the outspoken Jeff Kennett serving as Hawthorn president re-define the image of his AFL club?

Has Carlton lost its right to “entitlement” by its failures, including the self-inflicted wounds from the salary cap breaches two decades ago, amid a 25-year premiership drought that includes famous slogans such as the “They Know We’re Coming” for 2009?

So who are the entitled ones? And why?