Melbourne’s Angus Brayshaw resumed late in 2017, wearing a helmet, after repeated concussions put his playing future in doubt. Photo: GETTY IMAGES

Football concussion studies going back to the grass roots

The long and short-term effects of concussion are scary.

From headaches, dizziness and nausea to lasting mental health battles, the mystery of what happens to your brain when you sustain even a small head knock has consequences beyond the game itself.

Athletes playing contact sports seem to be bigger, faster and stronger than ever before. Thus, the need for greater care from sporting bodies is vital.

The United States has for a long time led the charge in investigating what damage can be done while playing high-impact sports. National pastimes such as American football, ice hockey and lacrosse produce brutal hits throughout every match.

However, botched research undertaken in partnership with the NFL has tarnished the image of a nation and its commitment to tackling this issue.

Until recently, it seemed that the AFL had been ignoring the danger signs in our own game, a game where players are lauded for delivering the perfect “hip and shoulder”.

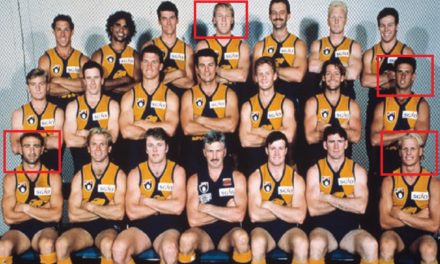

A trip to YouTube will show highlights packages from the AFL/VFL in the 1980s and 1990s showcasing earth-shattering bumps as great plays, and holding up those “brave enough” to play on after copping these hits as footy heroes.

Despite the AFL having no visible concussion policy until recently – indeed, the strict version of football’s concussion protocol was only introduced to the league in 2015 – Australian researchers have hit the ground running, but associate professor at La Trobe University Alan Pearce says there’s still a long way to go.

“There’s a lot of self-promotion in terms of how far we are going, but the reality is that we’re still well behind what’s happening in the United States,” he says. “Each month, the National Institute of Health in America have a database called PubMed, and they publish, every month, what the latest research is.”

“There’s about 50 articles that come out almost every month, and maybe one or two would be Australian research, but the rest is all American.

“They’re putting in $100 million into research in this area, whereas the AFL – recently with the AFLPA – released the fact that they’re going to be investing about $250,000. So you can’t compete.”

Pearce, a neurophysiologist and expert in concussion, is due to roll out a world-first field study using an Australian-designed mouthguard (the Nexus A9 by Hit IQ) that can sense and track head impacts.

Rather than using elite athletes for the trial, senior and reserves players from the Strathmore Football Club in the Essendon District Football League have volunteered to wear the mouthguard.

“I suggested that, as everyone is focusing in on the elite…the bigger issue that I’ve found, just from my other research, is that no one’s really looking after the people that play at sub-elite and community levels, and they suffer from concussions and head trauma as much as anyone else, but no one is looking after their well-being,” Pearce says.

“At that community level we’re seeing that you’ve got guys and girls that might not have been taught properly how to tackle. So even though the level of impact may not be as high as what we see in the AFL, what you find is that there’s no one there to make sure that they’re doing it right, that there’s no one on the sidelines to look after their health, other than a sports trainer – who’s really not in a position to make complex neurological decisions regarding concussion.

“Then you have them getting up and giving the cultural ‘I’m OK, there’s nothing wrong with me’ approach, and then having a few drinks after the game, which is probably the worst thing they could do.

“That’s what makes this a world-first. No one is really looking at that level of football.”

The past failings of the NFL have in many ways given the US something for which to atone. The commitment to correcting those earlier errors show not just in the funding being provided, but in the comprehensiveness of programs, such as the Brain Bank.

In Australian sport, and in particular in the AFL, there is certainly a lesson to be learnt from these experiences. But as Pearce says, it’s crucial we don’t simply wait for the worst to happen before we take action.

“I think what the AFL have learnt from that (the NFL’s research), very quickly, is that they’ve got to accept that it is an issue – and to a certain extent they have,” he says. “They’ve changed their policies; they’re much stricter now on head-high hits. So, in that sense they’re going in the right direction.

“One of the things that was a catalyst for America to get the Brain Bank was a number of high-profile suicides by NFL players. So if the most unfortunate thing happened here in Australia, where several AFL or NRL players committed suicide through depression, that might be the unfortunate galvanisation to go: ‘OK, we have to do something about it’, but because nothing has happened here like that, there hasn’t really been any reaction.

“This is something that is not going to go away. If they don’t do anything about it, it’s just going to get worse.”

But the AFL at least has all of the information in front of it, and, via the NFL example, a cautionary tale of what not to do, and how a swift response can lead to better outcomes.

These better outcomes won’t improve the league’s bottom line, or the quality of football played, but it will quite possibly spare us the sort of tragic post-career tale which has become too frequent in American football.

“We don’t know, at the moment, if head trauma has contributed to a number of young men’s suicides, compounding any underlying depression or anxiety, which has then been exacerbated through brain trauma,” Pearce says. “We have no data on that.

“But we have such a huge number of people playing weekend sport, we do need to do better in that area.”