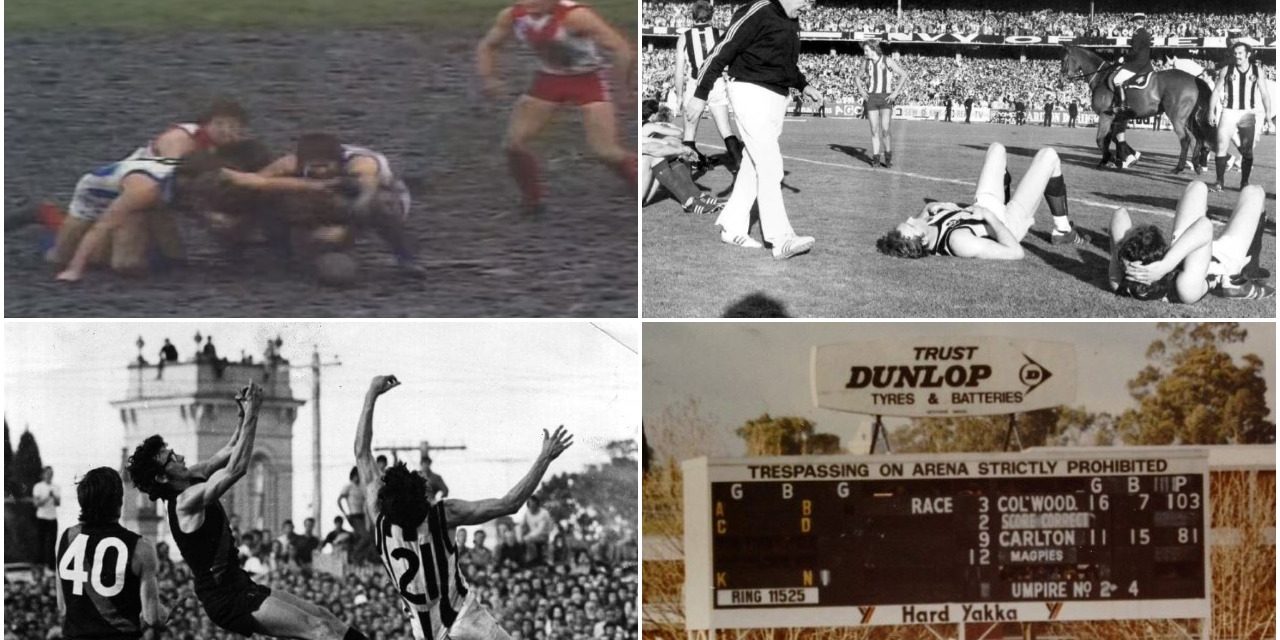

Clockwise from top left: A muddy Lake Oval, the 1977 grand final draw, Victoria Park scoreboard, a packed Windy Hill outer.

In the last day or so I have begrudgingly come to accept a most inconvenient truth. I am the wrong side of 50.

Whilst that admission may suggest I have only recently raised my bat for the half-ton, the truth is that I’m a 54-year-old married white male living both in Victoria and in denial.

My awakening was forced upon me by a wife who took it upon herself to divest the family home of items she feels a man of my age could not or should not possess. I watched as countless overstuffed black garbage bags were removed from the house by her and our children, held as far away from their person as possible, so as to make it look like they were handling evidence bags from a gruesome crime scene.

Those bags DID contain evidence of a crime and it is one we are all guilty of committing in some form or another.

The crime I speak of is trying to resist the ageing process. Apparently I was doing that by maintaining a wardrobe that made sense when I was 35 but now is just the sign of a man who can’t let go. To help me move from the past into the present it was decided that clothing and other vestiges of the younger me had to go.

Good-bye size 32 jeans, au revoir boxing gear, sayonara in-line skates and adios to nearly all of my T-shirts. My much loved tees were being culled because, as my wife informed me, men of my vintage don’t get about wearing tops smothered in slogans or imprinted with an image of Einstein smoking a bong.

With clothes and potentially lethal sporting goods on the way out, I began to warm to the idea of a more age-appropriate me. To truly embrace moving forward as a 48-year-old (baby steps here people, I’m not ready to tell the whole truth just yet) I would need to develop the right mindset.

It’s out with the old and in with the new. Technology, music, television and language have all received an upgrade, leaving just one major component of my being to attend to.

Needless to say that is footy. The “back in my day” attitude that is so common among fans in my age bracket has to go, and to make that happen, I am binning those remnants of the past that I will never see again.

So in keeping with that spirit, and as much as I wish they hadn’t gone the way of the dodo, here are the things we will never see in the AFL again.

GRAND FINAL REPLAYS

Given the trauma I suffered as a result of the drawn grand final and subsequent replay in 2010, I have little trouble in waving this one goodbye.

It’s interesting to note that the AFL didn’t legislate the replay out of existence until the start of the 2016 season.

With that ruling, Collingwood and St. Kilda in 2010, Collingwood and North Melbourne in 1977 and Melbourne and Essendon in 1948 will remain the only years in which the grand final was drawn, resulting in a rematch the following week.

All other finals have been subject to extra time since 1991, with the 1990 Collingwood and West Coast qualifying final replay the last of its kind.

Since then, three finals have required an extra 10 minutes of play to find a winner, and it seems right that one of those matches was between the two teams that precipitated the move to do away with replays in the first place, the Pies and the Eagles, who went into overtime to decide the 2007 second semi-final.

MUD-HEAPS

I’m not sure why I remember these fondly, but they certainly were part of football in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Most VFL clubs shared grounds with district cricket clubs, and in the middle of those ovals lay cricket pitches.

The soil favoured to produce the best turf pitches was a blackish mix of rich soil and soft clay that originated from a place called Merri Creek.

Truckloads of the stuff made its way to Melbourne. Whilst it made for the ideal cricket surface when allowed to bake under a summer sun, just add water for a mud so thick it would take three showers to wash off.

Some clubs like Essendon managed the situation quite well, while others were less successful.

South Melbourne’s Lakeside Oval was a notorious mud-heap. Curiously, it behaved like male pattern baldness, with winter-grass loss radiating out from ground’s centre.

Starting in May, grey clouds would roll in from Port Phillip Bay and dump their contents on to the playing fields around Albert Park Lake. Initially, these showers turned just the centre of the Swans’ home ground into a quagmire, but after a couple of games, the entire playing area became one foul-smelling glue-pot.

The Hawks’ old home, Glenferrie Oval, was similarly afflicted, whilst Moorabbin also had the tar-pit look going on. In St. Kilda’s case, there may have been some human intervention, as certain officials took drastic measures to keep the margin of defeat down during the ‘80s.

The football that was played on these grounds would be alien to young fans today. What it lacked in skill it made up for in physicality, a word commentators came up with for just such conditions. Players seemed to lose their inhibitions in the mud, or maybe they thought they were unidentifiable when caked from head to toe in the stuff.

Whatever their reasoning, many a mischief was committed by men when Merri Creek soil was underfoot.

Today, we have retractable roofs, drop-in pitches and “super-soppers”. There are even turf experts whose sole job is to ensure that footballers and mud never co-mingle again.

One would have thought that those measures would have been enough to eradicate the dreaded mud-heap for once and for all, but the AFL wanted to make sure, so what did they do? They built a football stadium on top of a car park. There’s no mud, but plenty of reasons to wish there was.

THE OUTER

The very words speak of a place set aside for the unwelcome. In the ‘70s, the word outer was associated with outer space or outer limits and conjured up an image of a bleak wilderness from where you would most likely never return.

Maybe that was the idea, make the outer sound so uncomfortable that fans would pay a premium not to be there, or perhaps the outer got its name from the lack of amenities within its borders.

After all, the outer was always “outa” hot pies by quarter-time, “outa” cold beer by the long break, and home to a pre-war toilet that if not “outa” order would definitely be “outa” dunny paper.

So where were these neglected patches of land? And what exactly were they?

Other than the MCG and VFL Park in Waverley, all league grounds had an area known as the outer. It was a terraced section of the ground, devoid of seating, save for a curious single bench up against the boundary fence that ringed the entire oval.

Generally positioned directly opposite the main grandstand, it was populated by fans of the away team, a scattering of neutrals, and an odd mix of home supporters, loosely made up of those who couldn’t afford a seat, others who actually preferred to stand at the football (such as myself) and a certain type who, let’s just say, enjoyed interacting with opposition fans at close quarters.

Whilst the broad brushstrokes were shared, every outer had its own character.

Then outers at Victoria Park, Windy Hill and Princes Park were the most crowded and in turn the most threatening. They say there’s safety in numbers, but in a footy crowd a more accurate saying would be that there’s bravado in numbers.

The above mentioned grounds were home to the league’s biggest clubs, Collingwood, Essendon and Carlton, and their outers were always packed tight with supporters of both sides.

I found the outer at Essendon the most intimidating. I say that because Windy Hill was where a large man standing directly in front of me tried to knock my head off with a family-sized shifter.

The fact he had a massive wrench down one of his boots was bad enough, but his willingness to brandish it and the support he drew from fellow Essendon fans when he did, made me tread gingerly at Windy Hill from that day on.

The outer at Victoria Park was also no place for the weak. You were always packed in like sardines, and it paid to remember that the man or woman pressed up against you was probably there because they were deemed too uncouth to sit in the grandstand, which at Victoria Park is really saying something.

The other thing you always had to be aware of in the Collingwood outer was that in case of an emergency, it was impossible to bid a hasty retreat.

If the mob turned on you, there was not much you could do so tightly was the crowd wedged in. Like a Tetris piece out of options, you had to wait for others to vacate before you could do likewise. As a result, cutting remarks tended to be whispered rather than shouted at “Viccy Park”.

Not all outers recreated the crowded peak hour train experience, and not all outers were warzones.

Footscray played at the Western Oval, and generally it was fairly sparsely populated with very few home fans. There was no lack of home support in the Geelong outer. They tended to be a little subdued and quite friendly, at pains it seems to portray rural life in the best possible light. I did find that a combination of country bumpkin jokes and poor umpiring decisions against the home team could turn the hayseeds quite nasty.

The most interesting of all outers, though, had to be North Melbourne’s Arden Street. There you were treated to a group of regulars like no other. That single row of bench seating was unreserved, but at Arden Street it seemed to be taken up by the same group of fans year in year out.

No matter how early you got in to the ground, they were already there, snowy-haired North supporters that looked like they’d jumped straight out of an ad for home baked apple pie. They may have looked like your grandmother, but that’s where the comparison ended.

They cheered every North player either by nickname or first name, whereas the opposition were subject to a barrage of vitriol, most of which you still can’t put into print over 30 years later. And it was bad luck for any player from the opposition who got too close to the fence. They were fended off with a whack of the umbrella or sharp prod of the knitting needle.

They may have been unwelcoming and devoid of facilities, but each outer had a character all of its own, which helped to define the side that played there.

Sadly, they are now a thing of the past, as the new homogenised football stadium fills all available space with seating that can be sold at premium prices. There’s no free ride at the football any more, or the adventure that went with it.

THE DROP KICK/STAB PASS

Today, 95 per cent of intentional kicks in the AFL are drop punts. The remaining five per cent are banana or checkside kicks, used by some players even when they have nothing to bend the ball around, dribble kicks for footballers with a fear of flight, and the occasional torpedo punt, so rare that when correctly executed, it actually makes commentators squeal with delight.

The one kick fits all game we now watch may be a more evolved version of the game I fell in love with 40 years ago, but it’s not as fun to watch. I can say I saw the last of the drop-kicks, majestic when properly executed and laughably embarrassing when not.

The last we see saw of the drop kick was in the backline. Players who began in the ‘60s such as St Kilda’s Kevin “Cowboy” Neale, Richmond’s Dick Clay and North Melbourne skipper Barry Davis, were still sinking the slipper into the Sherrin old-school style until the mid-‘70s.

The drop-kick may have been a risky gambit, but not so the stab pass when coming off the boot of some of the game’s greats.

A miniature form of the drop kick, it was used by skilled centremen and rovers to pinpoint a pass to a leading forward. A well struck stab pass was impossible to defend, scything low through the air from kicker’s boot to recipient’s chest.

I witnessed the last masters of the art. Barry Price of Collingwood, who stab-passed the ball to the great Peter McKenna with a surgeon’s precision, and Barry Cable, the little North champ who was still spearing the stab pass as late as the 1977 grand final.

There was Cable’s teammate, the cheeky John Burns, who claimed he could knock a fly off the rim of a full beer glass with a stab pass at 25 metres without spilling a drop. That may have been a tall tale, but Burns could certainly deliver a stab pass with the best of them.

Fear of failure and no time set aside for players to work on their kicking skills means we’ve seen the last of the drop kick and the stab pass unless there’s a brave youngster out there who is willing to test his mettle with the full array of kicks the game has produced.

Fingers and toes crossed that there is.

WATERLOGGED BALLS

There was a time when football was played on muddy grounds in the pouring rain and unless a fan nicked it, only one footy was used for the entire afternoon. Be it a TW Sherrin or a Ross Faulkner, depending on which one the away captain preferred, the ball that started the game would end it. On a wintry afternoon, that ball finished the match in a very different condition to how it began.

A Sherrin weighs about 16 ounces out of the packaging, but kick that through puddles and mud flats all arvo and you can have a ball weighing more than twice that by game’s end. A waterlogged footy is no fun to mark, and it bent and dislocated fingers on the hands of players silly enough to attempt anything other than an old-fashioned chest mark.

Kicking the sodden ball was no bargain either. Ever tried to kick a small boulder over your back fence? Players with a set shot 40 metres out from goal that had to contend with a slippery, soaked football may as well have been kicking from the next suburb.

The aesthetic of the game is now paramount and there is no longer a place for the waterlogged ball. Bins full of shiny red Sherrins are located at each end of the ground, meaning there is virtually a new ball on the field at all times.

Nothing but the best for our pampered players in 2019.

MANNED SCOREBOARDS

If you’re at the footy this weekend and want to know the score, look up at the giant TV. The progress score is hiding somewhere among the advertising, the endless rolling stats and for the true TV addict, vision of the game you’re actually watching live.

It’s a far cry from the manned scoreboards that were a feature of every suburban ground back in the days of the VFL.

The scoreboard was a mighty edifice located in the outer. It was so positioned to face its intended audience of predominantly home fans, and it provided far more information than just scores.

Race results were posted for punters who chose the footy over the races, and that occasionally included some of the actual payers. The final score of the “Little League” game played at half-time stayed on the board for the remainder of the afternoon, albeit directly under advertising signs such as “Anyhow, ‘ave a Winfield”.

There was the number of the winning ticket in the club raffle, attendance figures that were posted late in the last quarter, and most memorably, quarter by quarter scores from other grounds that could only be deciphered with the help of the “Football Record”. The umpires were listed by number, once again requiring the record for decoding.

So who manned these towers of information? Unlike in the VFA, where attendants, usually underpaid teens, hung out of an opening to watch the game, the VFL scoreboard attendants remained unseen by the public. As teams scored or information needed to be conveyed to the crowd, they positioned metal plates that went from 0 to 9, wounds rolls of calico with numbers on them, and spun wheels with unerring accuracy and speed.

The old scoreboards were three or four storeys tall. I imagined muscular men bouncing from one level to another on ropes, Quasimodo-like, though I never got to peek inside. How they actually provided us with all that information described above remained a well-guarded secret.

The start of the end for the old giant blackboard type scoreboards came when VFL Park Waverley unveiled its quarter acre of light bulbs in 1982. The matrix screen scoreboard showed replays for the first time in Aussie Rules history, and to make it feel like a historical event, the images appeared to be in sepia.

Sadly, our obsession with all things technologically new has seen the majority of the old manned scoreboards thrown on to the scrap heap, but I ask you, are we any better off?

So there you have it. Experiences I had as young footy fan that my kids and their kids will never get to enjoy. I can imagine some of you asking who would want to relive the outer, games brought to a near standstill by ankle-trapping mud, ultra-heavy footballs and drop kicks flying off the boot like a square cut?

The answer is me and countless thousands like me, because it was footy before the marketing majors from Poindexter University got to it.

So, darling wife of mine, I stood back and let you bundle up my best years in garbage bags and did nothing. I watched in silence as you and our children tossed happy memories of a sleeker me into a mini-skip, without pause to reflect or regret. I took your advice to download, downsize and bow down to the wisdom of youth, but I am doing a Dermie and drawing the line in the sand.

When it comes to footy, I steadfastly reject the present and have no stomach for the future. I will not bin memories of the game I loved, viewed from the outer whilst performing a balancing act on a couple of empty “blue soldiers”.

Great column, Mark! As a 54-year-old man, we share many of the same references. I’m long gone from Melbourne (living in San Francisco for the past 15 years) but I share the bitter disappointment of the 2009 St. Kilda Grand Final loss to Geelong (flew back for the game). Cheers!

🇾🇪🇾🇪🇾🇪🇾🇪Hey Robert ,

As a 54 year-old Saints fan, If I can’t write an article that resonates with a 54 y.o. Saints fan

I should put the pen down forever Thanks for the communique and I hope the podcast scratch that weekly footy itch.

If you really miss that Saints experience I’m sure the ‘49ers can take you on a similarly frustrating journey. 🇾🇪🇾🇪🇾🇪🇾🇪

Stay well,

Finey