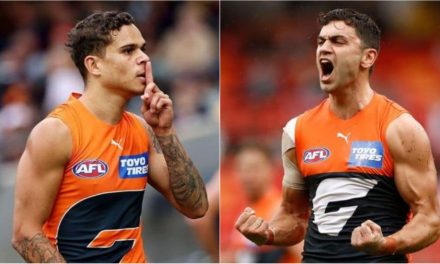

(From top left, clockwise): Rutten and Worsfold, Roos and Goodwin, Malthouse and Buckley, Longmire and Roos.

AFL football can often be an exercise in fashion. A club latches on to an idea or trend which works and in the blink of an eye, a host of rivals are following suit, hoping to also turn heads.

Some are successful. Then there are some fashion disasters. And after recent events, one footy fashion trend you’re unlikely to see too much of for a while is the coaching succession plan.

For that – depending on your view of the wisdom of the coaching handover – you can thank, or blame, Essendon. To say the Bombers’ transition from John Worsfold to Ben Rutten in the coaches box has been untidy would be an understatement, certainly in terms of public perception.

After a year of (officially at least) joint responsibility, Rutten steps into the role in his own right in 2021 at the helm of a splintered and unhappy playing group.

Several key players — led by Joe Daniher, Adam Saad and Orazio Fantasia — are reportedly on the verge of leaving, and a couple of very senior hands in Cale Hooker and Michael Hurley openly challenged the decision not to give retiring colleague Tom Bellchambers a farewell game.

Is that necessarily the result of too many cooks in the coaching kitchen? No, but some mixed messaging clearly didn’t help, and to that end, the decision to leave Worsfold as the sole coaching spokesman while Rutten pursued his work behind the scenes was a public relations disaster.

It’s nearly a decade now since the game’s other most-remembered coaching succession plan – that of Mick Malthouse to Nathan Buckley at Collingwood – was enacted. And until the Magpies reached the 2018 Grand Final, that, too, was viewed as a car crash.

As Collingwood topped the ladder in 2011 and prepared for a shot at a second consecutive premiership, the impending change proved the most unsettling distraction possible.

It got to everyone. From president Eddie McGuire, who had to address the situation on an almost daily basis. To Malthouse, never really on-board with the idea, who suddenly found himself on the verge of his greatest success but simultaneously forced into relinquishing the reins. And, of course, Buckley, who later conceded he’d considered during 2011 asking the club to delay the change.

It was a messy business indeed, the rubble still visible a good six years later by way of occasional skirmishes, ruffled egos and the odd barb here or there from all involved.

But is the coaching transition always a guaranteed disaster? Not necessarily. From a sample of four over the past decade, I make the scoreline one win, two losses and a game still in progress.

The win, funnily enough, you hear very little about these days. It was the succession of John Longmire from Paul Roos in the driver’s seat at Sydney. And one which could not possibly have been smoother.

The most obvious reason was because Longmire had been an assistant to Roos from the time the former champion defender took over the job from Rodney Eade midway through 2002.

Nine seasons under Roos included almost annual finals appearances, two Grand Finals and a premiership. It gave Longmire plenty of schooling in the ins and outs of the list, the Sydney ethos, game plan and what worked and what didn’t.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Longmire had added a little more dash and dare perhaps to the Swans combination which ended up winning the 2012 premiership in his second year as the main man, but the most essential work had been done.

Roos would go on to a second transition phase, at Melbourne. Simon Goodwin became the heir apparent only in Roos’ second season with the Demons, the apprenticeship lasting two years.

The on-field results under Roos by the time Goodwin took over the job were hardly spectacular, but Melbourne had shown continued improvement in three years, particularly in their capacity to defend.

Perhaps more importantly, though, Roos’ imposing reputation in the football world had helped steady the ship in terms of a whole club, the faction fighting and cultural baggage which hung heavy in the wake of the Mark Neeld sacking in 2013 largely settled.

Goodwin has his critics, but in four seasons since Roos has at least taken Melbourne to a top four spot, higher on the ladder than any coach since Neale Daniher in 2000, plus two ninths, last year’s disaster the only obvious exception.

There was always at least the sense when he assumed the reins in 2017 that the Demons were continuing to build on Roos’ legacy. Progress may have been slower than a lot would like, but nonetheless, the direction has still overall clearly been forward.

That isn’t a luxury Rutten will have at Essendon in 2021, the Bombers (unless they are completely delusional) now headed for a major list overhaul.

Off the field, meanwhile, there’s much angst about the club’s entire direction. And Essendon has always been a club where the influence of past greats and corporate patrons remains profound. They’ve already proved on several occasions over the years they can not only rock the boat, but tip it over.

That might not seem quite as likely a prospect now had Rutten already assumed the reins in his own right for 12 months, been seen to be the only man steering the ship, and having given the Essendon administration a chance to actually demonstrate its support of him rather than awkwardly tip-toe around his still-present predecessor.

In the case of Collingwood, make that excruciatingly awkward for those 12 months between the Pies winning their 2010 premiership and 2011 Grand Final loss.

The lesson in all this may well be not that coaching succession plans are inherently doomed to failure, but that the bigger the club in terms of status, support and media real estate, the less the likelihood of a smooth handover.

Swans supporters, steeled on some pretty miserable eras both under the old South Melbourne banner and even post the club’s shift to Sydney, have always shown enormous trust in those that run the place. Melbourne, after so long in the doldrums, was prepared to take what it could get.

Collingwood and Essendon, meanwhile, have always been, and remain, brash, loud concerns, where there is never any shortage of differing opinions, nor dissent.

It took Buckley more than five years to completely shed all the baggage the bequeathing of the Magpie coaching job to him caused.

It’s already obvious Rutten won’t have anywhere near that long to do similarly at Essendon. Particularly given the nature of the club he’s now coaching on his own.

This article first appeared at ESPN.