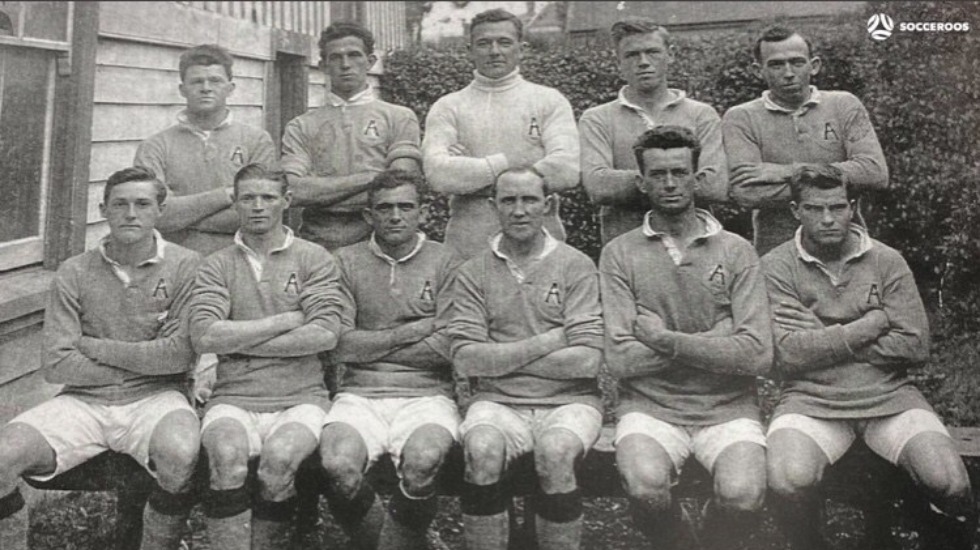

The first Socceroos team which played against New Zealand in 1922. Photo: FOOTBALL AUSTRALIA.

As the AFL and NRL seasons reach their climax, it’s been fascinating – for someone who doesn’t follow either code – to witness the depth of media coverage given to the protagonists ahead of these big end-of-season games.

In particular, it’s hard not to be drawn to items such as the one on the Norm Smith “curse” – Smith being the last coach to guide Melbourne to a grand final win in 1964, then sacked a year later.

From this article, I learned Smith has the best-on-ground medal in the showpiece occasion named after him, and a statue outside the MCG. There was also the story of the Demons 1964 flag, stolen by an enterprising child, and used as a bedspread for years, until it was found just last week.

In Sydney, there’s a terrific heritage story in the shape of David Cartwright, a former Penrith Panthers player, who was the son of Merv Cartwright, the club’s founding father, brother of club playing legend John – and father of Bryce Cartwright, who will play against the Panthers this weekend for the Parramatta Eels.

Why do these stories that hark back to yesteryear have such impact? Because they tell the stories of “us” as a nation, as a sporting community. Tales and legends to be handed down to the next generation. In the words of the American author David McCullough, “History is who we are, and why we are the way we are.”

But in Australian terms, the “royal we” tends to exclude the sport of association football.

For sure, the tales of the 1974 Socceroos and their feats in qualifying for the World Cup vaguely resonate among the general population. Rale Rasic and Johnny Warren (the latter, in part for his work on SBS Television) are names familiar in at least some households across the country.

In the modern era, the achievements of the golden generation in 2006, and the female equivalents that have followed to make the Matildas a competitor on the world stage, are reflected in relatively sharp spotlight.

Yet generally, the history of football in Australia remains a foreign country – which of course, is where many believe the sport belongs.

Victorian academic, Ian Syson, summed up the dilemma in his book “The Game that never happened – the vanishing history of soccer in Australia” as he told the story of how the game’s past has been forgotten and ignored, in part through nefarious intent from outside, but also through the apathy and a lack of proper, organised curation from within.

Many attempts have been made down the years to try to rectify this state of affairs. All have succumbed to the sport’s ever-present need to live in the moment, its struggle just to survive and try to create a better future. Nostalgia is a luxury you can’t always afford when fighting to put bread on the table.

Yet those tales of the past can be so instructive and helpful in creating that sustainable future. Legends such as Norm Smith and David Cartwright construct narratives that bleed through the generations, fostering a sense of permanence and belonging. Identity, for the clubs, the sports, and the connection to the communities where they are played.

It is little wonder Smith is immortalised outside the MCG. It is there that Australian rules football (along with cricket) has its own sacred ground, and the deeds of those who found success there echo through the years, to educate supporters and nurture the love and understanding of the game.

Where are football’s? In truth, the answer is – in pretty short supply.

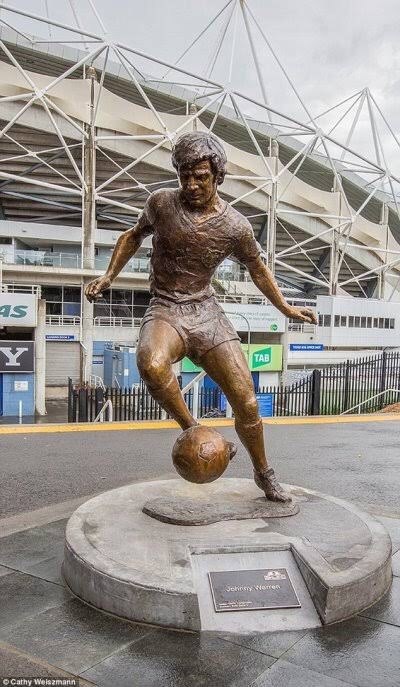

Johnny Warren does have a statue outside the Sydney Football Stadium, and there is one of Ferenc Puskas in Melbourne that recently fell into disrepair. But otherwise, the stories of our heroes go largely untold, at least outside the immediate football community.

Johnny Warren’s statue outside the Sydney Football Stadium. Photo: CATHY WEISZMANN.

When I suggested recently on ABC’s Offsiders program that Ange Postecoglou should be cast in bronze in his home city of Melbourne, the response was largely one of incredulity.

Some complained that he’d “not yet won anything” – which, for a coach with four national titles, an Asian Cup, a J-League championship and an Australian record 36-game unbeaten streak on his CV (he has won 22 major honours in total as both player and coach), tells its own sad story.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Next year, the Socceroos will mark the centenary of their very first international (against New Zealand in Dunedin in 1922). There will be some sort of celebration – potentially a rematch – and to be fair to Football Australia, there are also strong rumours they may revive the “Australia Cup” name to replace the FFA Cup in 2022, in honour of the very first national Cup competition that started back in the 1960s.

But even among the football community, names such as Alec Gibb (the first Socceroos captain), or Bill Maunder (first goal scorer in that game against New Zealand) are largely absent from memory.

There are many reasons for this. Part of the problem is football’s lack of true homes to display such memorabilia and tell such stories. There is no football equivalent of the MCG – although again, the FA is attempting to rectify this, using the hosting of the FIFA Women’s World Cup in 2023 as leverage to obtain some long-overdue government funding.

But it is also cultural.

As Ian Syson explains, football has been regularly marginalised, in part due to the ongoing code wars of Australia. The influx of migrants from southern Europe in the 1950s also made the “otherness” of many football lovers easier to identify and ostracise.

The football history that IS recognised has come to be largely defined by that era. The NSL that followed in its wake, and the specific migrant groups its clubs represented, became the embodiment of what “we” as a football community were. Some of those clubs – South Melbourne, Melbourne Knights, APIA Leichhardt to name but three – preserve their individual histories very well indeed.

Yet while the NSL was – and remains – a hugely important part of the game’s history (and then FA CEO John O’Neill’s infamous “old soccer, new football” dividing line didn’t exactly help protect that history when the A-League emerged in 2005), the game’s roots stretch back much further.

For example, in 2025, the very first officially recorded game will have its 150th anniversary, a match which took place in Goodna in Queensland in 1875. Last year was the 130th anniversary of the first “state of origin” football game, which took place between New South Wales and Queensland at Sir Joseph Banks Park in Botany in 1890.

The Playing field at Sir Joseph Banks Park. Photo: SIMON HILL.

Australia’s first football export, James Jackson, is another. Although born in Scotland, he arrived in Newcastle (NSW) aged two, and played for Hamilton Athletic and Adamstown Rosebud before signing for the mighty Glasgow Rangers in 1895.

Jackson’s sons both became footballers – the elder, James junior, played over 200 games for Liverpool. He had a brother who played for Scotland, and his nephew was the Australian cricketer, Archie Jackson.

Yet virtually no-one in Australia is familiar with the Jackson story – and while the first game of rugby league (which also took place at Sir Joseph Banks Park in 1908) is commemorated by a mention on a plaque at the site, the football game, which occurred 18 years earlier, is notable by its absence.

Plaque at Sir Joseph Banks Park commemorating the first game of rugby league. Photo: SIMON HILL.

It’s a similar story at Manuka Oval in Canberra – the site of the very first NSL game in 1977 (the first truly national competition of any football code in Australia), and Wentworth Park in Sydney, the home of the first Australia Cup Final in 1962. Nothing. There are many other examples.

The FFA Heritage Committee, formed a couple of years ago (and which, for transparency’s sake, I was a part of) aimed to try and change that. We issued a plaque to be displayed at Seymour Shaw Park in Sutherland, the home of the very first Matildas “A” game in 1979. There were plans for others, along with the preparation of a list of the “first 500” clubs in Australia, with a map of their locations to be displayed on a heritage website.

Yet like so many things associated with the game’s past, it has fallen into abeyance – to be revived at some future point.

So while legends such as Norm Smith and David Cartwright get the veneration they undoubtedly deserve, our heroes languish in relative obscurity, our stories untold.

There are some very good football historians in Australia, but to change the narrative will require a Herculean effort, and the sort of unity of purpose the game isn’t exactly renowned for.

Until then, as Ian Syson says about the earliest games of football in Australia, these stories will “remain lost, because their discovery has little purchase.”