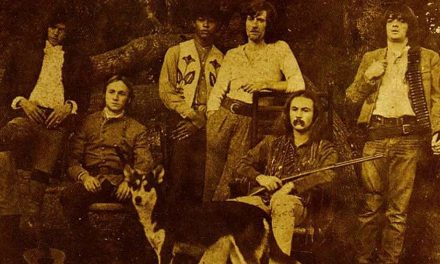

Tyias Browning, born in England to a Chinese mother, could face the Socceroos in World Cup qualifying for China on Friday. Photo: GETTY IMAGES

National identity. It’s a topical issue, and one that is causing waves, right around the world.

Populist politicians in particular, have latched onto people’s search for belonging. Think Trump’s “Make America Great Again” caps, Boris Johnson’s “Taking Back Control” slogan during the Brexit campaign, and virtually anyone here using “un-Australian” as a pejorative term.

It’s no accident leaders use such terms. They know they resonate. It’s about defining who “we” are.

Yet in a modern, globalised world, identity isn’t always easy to pigeonhole. I’m a prime example. Born in England, I lived there for 35 years before emigrating to Australia. I hold passports for two nations. Many in Australia are the same.

I’m usually labelled as “English” here, yet back in my homeland – particularly as the years have passed – it’s the opposite. This leaves the individual in something of a neutral zone when it comes to identity. A good friend of mine with the same background refers to it as “limbo-land” – belonging to neither one, nor the other.

When it comes to sport, particularly of the international variety, the discussion should probably be a lot clearer. Yet it isn’t – and sport is not immune from the ebbs and flows of the society in which it exists.

As long ago as the 1970s, Kepler Wessels wore the baggy green after arriving in Australia to play World Series Cricket. In those days, his native South Africa was banished from the international arena, so his choice was doubtless conceived of necessity. Charles Bannerman – the scorer of Australia’s first-ever runs in Test cricket – was born in England, although he moved Down Under as a child.

More recently, Tatiana Grigorieva won pole vaulting silver at the Sydney Olympics after leaving Russia in 1997, and Kostya Tszyu became world light welterweight boxing champion after arriving here following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the ’90s. There are countless other examples in many countries.

Football, as the most global sport of them all, has been particularly susceptible to this trend.

The first Socceroos squad to reach the World Cup Finals in 1974 was made up largely of immigrants – six Englishmen, four Yugoslavs, three Scots, a German and a Hungarian made up the 22-man squad alongside only seven native-born Australians.

Yet all of those players moved to Australia with the intention of building new lives, many due to the political, or economic, tumult of life in their homelands.

Nearly all stayed, long after their playing days were over – and that lineage continues today with the likes of Awer Mabil part of a fast-emerging generation of footballing talent from the African diaspora; the offspring of families displaced by the wars in South Sudan, Liberia, Rwanda and elsewhere.

Refugees aside, FIFA, as the game’s governing body, used to have fairly strict rules on eligibility. Tim Cahill, for example, had to wait years to make his Australian debut after representing Samoa (the country of his mother) at a junior tournament.

But they relented in 2004 – and since then, the criteria has been relaxed, tightened, amended, and then relaxed again. Players with biological parents or grandparents born in a particular country are now eligible to play for that nation. As of September 2020, players can also now switch nationalities if they have played no more than three competitive games at senior level for another country, prior to the age of them turning 21.

Australia has benefited from some of these rule changes – and not just with Cahill. The modern squad contains Martin Boyle and Harry Souttar, two players whose accents would not be out of place on the streets of Glasgow. Milos Degenek (Serbia) and Brad Smith (England) both represented other nations at junior level.

Yet these rules – and the controversial “residency” clause in particular – have also been exploited to their fullest by emerging nations eager to catch up to the established football powers. Qatar’s squad for the recent CONCACAF Gold Cup for example, contained 11 (out of 22) players born overseas – three from Sudan, two from Iraq and one each from Portugal, France, Algeria, Egypt, Ghana and Somalia.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

That’s not to accuse Qatar of breaking any rules – so far as I’m aware, they haven’t. But is it stretching the moral boundaries of international sport to have so many? Of the 11, how many arrived as kids? How many have been naturalised because of their talent, and Qatar’s financial muscle in being able to accommodate them? Does it even matter?

On Friday morning (Australian time), the Socceroos will face China in the opening match of the final round of Asian qualifying – the business end ahead of the finals, coincidentally to be held in Qatar in 2022.

China has recently joined in with the naturalisation game. In 2019, they began to naturalise players with Chinese links, in order to improve their underperforming national team’s fortunes. Nico Yennaris, born in England to a Greek-Cypriot father and Chinese mother, was the first – making his debut (and history) by starting against the Philippines in June 2019. He has since taken the name Li Ke.

Others have followed. And although Li Ke isn’t part of the current Chinese squad, on Friday, up to four could feature against Australia – including Tyias Browning (Jiang Guangtai), born in Liverpool to a Chinese mother.

The other three are examples of that reach extending further via the residency rules. All are Brazilians. Strikers Elkeson (Ai Kesen), Alan (A Lan) and Aloisio (Luo Guofu) have no Chinese ancestry, but have played in the country for some time at club level.

In total, it’s reckoned there are around 90 Brazilians who are currently playing, or who have played for, countries other than Brazil. As long ago as 2007, then FIFA President, Sepp Blatter, said “if we don’t stop this farce, then in the 2014 or 2018 World Cup, out of the 32 teams you will have 16 full of Brazilian players.”

Does this make a mockery of international sport, when there is effectively, a transfer market for talent?

I have to admit I’m on the fence with this one. Who am I to say whether Elkeson feels Chinese, or not? Given China doesn’t recognise dual nationality, it’s a fair bet such decisions to commit are not taken lightly by those involved. Will he have the option of regaining his Brazilian citizenship should he so wish, after his playing days are over? It’s an extraordinarily complex issue.

As is the concept of “belonging”.

I remember during my days at SBS, some of my colleagues (of ethnic heritage) being irritated by the suggestion they should support the Socceroos over Croatia, or Italy at the 2006 World Cup, even though they had been born in Australia.

Their reasoning? They’d grown up being labelled “wogs” and outsiders, both for their heritage and for their love of football. They were singled out, identifiably different. Then suddenly, they were accused of being disloyal? I understood their argument.

Me? I feel a very close bond to the Socceroos. I feel they represent people of my “different” background, and helped my experience of acclimatisation to this country via the common bond of football more than anything else. Particularly when the game was (and still is) often labelled as “your” sport, in preference to “our” sport when referring to Australian rules football or rugby league.

Language matters, and when something you value is dismissed as being of lesser worth, you cling on to it all the more.

But then, at 53, I’m hardly likely to be asked to represent Australia at any sport, so my preferences are a moot point. For others, the choices are starker.

Zeljko Kalac famously sang both national anthems ahead of the Australia-Croatia clash in Stuttgart ahead of their World Cup meeting in 2006, and admitted to feeling slightly strange at attempting to beat a nation he was so closely aligned to in terms of his heritage.

Conversely, Francis Awaritefe (English-born of Nigerian heritage), once told me that the day he lined up in the green and gold and sang the national anthem ahead of his Socceroos debut, was the moment it all changed for him. He felt truly Australian after that.

In the end, perhaps it all comes down to the individual, and what is in their heart. Good luck coming up with a criteria for that.

Coverage of the game between Australia and China begins at 3.30am on Channel 10 & simulcast on 10Play.