There is a human greatness that keeps recurring through the turmoil of the ages – Uluru is our symbol of that.

Dear Australians of the Future,

I grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s not really knowing what it meant to be Australian. I am a Tasmanian of convict descent but didn’t know it when I was a child. Having a convict on the family tree was something that was hidden. What I did know was a lot of bushranger stories – Ned Kelly was big in our family.

The other thing I knew was the face of an old Tasmanian Aboriginal woman called Truganini who was said to be the last of her race. She had doomed, haunted eyes. No-one talked about the Tasmanian Aborigines when I was growing up beyond saying they weren’t here anymore.

The symbol on the Tasmanian flag was the lion of Imperial Britain. The only lion I saw was in a cage when Bullen’s circus came to town. I knew my forebears were from Ireland so, at the age of 23, I went there, thinking I might be Irish. I was in one way but not in another. I had this other part to me and the word I eventually gave that other part is Australian.

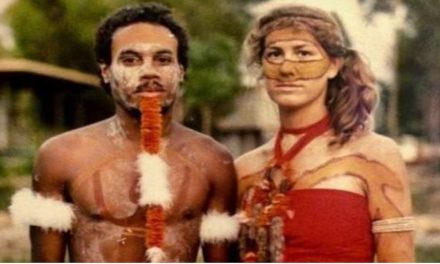

I wandered the world for two years, came home and got a job as a journalist. Over the next 36 years I took every opportunity that came my way to spend time with Indigenous people, in the city, in the bush, in the Torres Strait, in New Guinea.

I was present the first night Archie Roach sang to a white audience. I remember thinking I had been waiting my whole life to hear a voice like his. It was utterly authentic and true to historical fact, but, notwithstanding the injury done to him and his people, his art wasn’t angry. It was way deeper than that. I wrote an article for “The Age” and called Archie “the voice of Ulruru”. What I meant was that, throughout the world, there is a human greatness that keeps recurring through the turmoil of the ages and which, in that sense, is timeless – Uluru, the old Rock at the heart of our nation, is our symbol of that.

During World War 2, my father was in the army with Weary Dunlop. Weary was my idea of a great human being. By great, I don’t mean perfect. I mean out of the ordinary, larger than the rest, like a great mountain on the horizon. I got to know other old Burma railway survivors like Tom Uren and Blue Butterworth. They’d seen a lot, had suffered, were compassionate and wise – they were like elders to me, people I aspired to be like. Then, when I went into Aboriginal Australia and started meeting Aboriginal elders I found they were remarkably like the old Burma railway men – people who had seen a lot, had suffered, were compassionate, were wise….I’m talking about the likes of Archie Roach, Patrick Dodson, Joy Wandin Murphy, Uncle Banjo Clark, Michael Long and, most recently, Tasmanian elder Patsy Cameron.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

In the 1990s, whitefellas like me were said to be part of the “black armband brigade”. The suggestion was that in seeking a closer relationship with Indigenous Australia, we were motivated by guilt. I wasn’t. The reason I wasn’t was because not one of the great elders I met expected it of me. As I see Indigenous culture, it’s predicated on respect. If you’re respectful and know your place, my overwhelming experience is that you’ll be fine with Indigenous people.

I would never suggest the road to reconciliation is simple or straightforward – or, indeed, that it ever ends – but the reason I have walked it is because ultimately I found it rewarding. And what’s the alternative? Pretending Australia started in 1770? Imagine if the English were told that henceforth they were to consider that English history was only what had occurred since 1770 – no Shakespeare, no Stonehenge, no Magna Carta, no Picts, no Celts, no Hadrian’s wall … it would be rightly seen as absurd. Two thousand years ago a Roman playwright called Terence said, “All that which is human is part of me”. I say all that which is Australian is part of me.

Patrick Dodson has a saying – he will describe individuals as “a serious person”, meaning they deserve to be listened to even if their viewpoint is not your own – because their views have gravity. The opposite of serious people are shallow, self-important people, many of whom are now to be found in the whirlpool where politics, the media and the entertainment industry meet and mix in western commercial culture.

I have one question for people who are dismissive of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Do they have an Aboriginal friend and what’s one thing they’ve learned from them? It occurred to me in the 1990s when I was being accused of being a member of “the black armband brigade”, that none of the people making those accusations ever showed any evidence of having any relationships whatsoever with anyone in Aboriginal Australia. On the few occasions when former Liberal Prime Minister John Howard visited remote Aboriginal settlements he looked bewildered, like an octogenarian who had staggered into the wrong ward.

I do not believe the Uluru Statement from the Heart can, of itself, miraculously bridge the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia. Nor will it be free of controversy. We now have a large part of our media dependant on controversy for its existence. But when I read the Uluru Statement I saw the wisdom I have grown to respect over decades. I am asking you, whatever your backgrounds, to read the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Yours most sincerely,

Martin Flanagan

Just shared this again. I hear your vice clearly. After reading your logic, and your appeal to our desire to be better, how could anybody disagree with the Voice?

Thank you also for that image of John Howard: it’s a pearler.

A beautifully clear message that promotes sober and fair consideration of a question vital to this country.

An antidote to the deliberate promotion of fear by much of the popular media and dangerously reactionary politics.

Fabulous! Thank you.