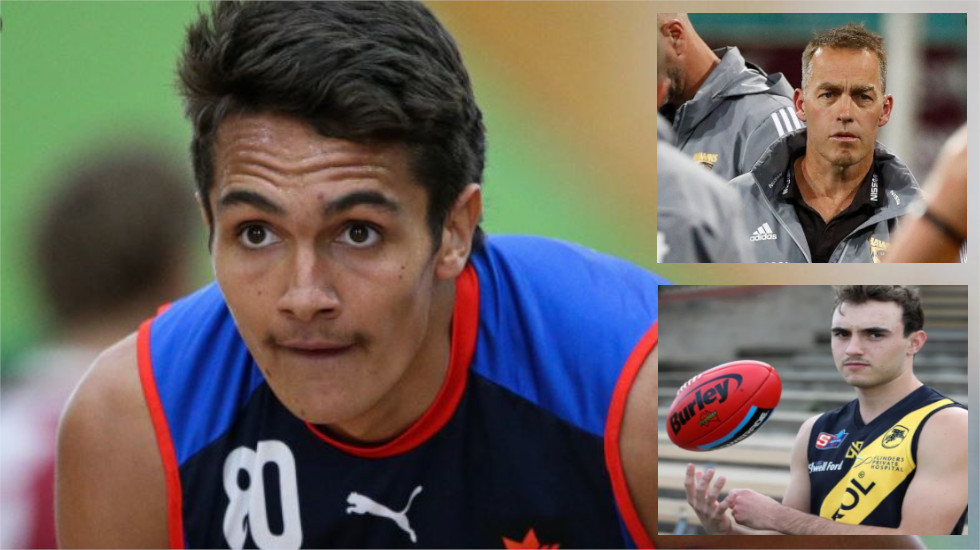

(Main image): The highly-rated Jamarra Ugle-Hagan. (Top right): Alastair Clarkson. (Bottom): Tyson Edwards’ son Luke.

It is such a simple concept. Reverse the order of the premiership table. Everyone gets one pick. Repeat.

Adelaide. North Melbourne. Sydney. Hawthorn. Gold Coast. Essendon. Fremantle. Carlton. Greater Western Sydney. Melbourne. Western Bulldogs. West Coast. Collingwood. St Kilda. Brisbane. Port Adelaide. Geelong. Richmond.

Fair – and equitable. The weakest team gets the first opportunity to recruit the best young talent outside the AFL system (as subjective as the task is, particularly in a season with junior competitions in the draft cradle of Victoria shut down by the COVID pandemic).

But next week’s AFL national draft will work to a very different script.

Wooden-spoon holder Adelaide indeed will have the No.1 pick. But the Western Bulldogs will get the game’s highest-rated recruit – Jamarra Ugle-Hagan – because the highly-regarded teenager is part of the Victorian club’s Next Generation Academy.

If the Crows call Ugle-Hagan at No.1 (worth 3000 points on the novel draft value index), the Bulldogs have to match the bid – minus 20 per cent – with draft picks worth 2400 points.

The indicative first-round draft order today is – Adelaide, North Melbourne, Sydney, Hawthorn, Gold Coast, then three consecutive picks for Essendon … but this could change with live trading of picks on draft day.

Fremantle’s first draft punt next week has been pushed out to No.12 to clear away the 264.9 points the Dockers chalked up as a deficit last year to keep its NGA prodigy, Liam Henry, after Carlton had called his name at No.9. Then Carlton list manager Stephen Silvagni forced the Dockers – in a so-called “keep them honest” moment – to cough up picks Nos. 49, 58, 66 and 73.

Port Adelaide faces this dilemma next week, particularly if Essendon bids on the Power’s readymade half-back Lachie Jones – another NGA draft prospect who could command a pick in the 6-10 range.

Port Adelaide has no first-round pick. The Power gave this call to Brisbane last year and the Lions have handed it on to Melbourne this year.

The first round of next week’s national recruiting lottery has 21 picks – not 18, as in one for each AFL club. This is a draft compromised by compensation calls made up by league headquarters to cover the loss of free agents: No.7 to Essendon for losing key forward Joe Daniher to Brisbane, and No.10 to Greater Western Sydney (Zac Williams to Carlton).

The third “extra pick” to make up the 21 is a concession draft call handed to Gold Coast in a special-assistance package last year – No.13 that has finished with Greater Western Sydney. It became part of the deal that closed Jeremy Cameron’s trade that allowed the key forward to join Geelong during the trade period after his free-agency play was blocked by the Giants.

The simple draft concept has been corrupted by layer on layer of adjustments, rule changes and special circumstances. Consult the AFL Record season guide, the so-called “bible” of the league’s history, and the adjustments made to draft system highlight a once-simple recruiting model overtaken by agendas.

The list reads – 17-year-old access selection (with Adelaide and Port Adelaide always to regret overlooking future Fremantle captain Matthew Pavlich in 1998); three-year non-registered selection; Brisbane/GWS/Gold Coast/Sydney academies; delisted free agents; compensation picks by free agency or to Gold Coast; father-son picks; GWS incentive rule selection with 17-year-olds; international and local talent access picks; NSW scholarships; priority picks; special assistance selections; zone selections and rookie elevations.

It is a far shift from the first national draft – one surprisingly ignored by the “bible” in another airbrushing of football history. On October 8, 1981, the 12 VFL clubs were each given two picks with the calling order decided by reverse premiership rankings.

Ultimately struck down, the first draft of national talent outside Victoria replaced those infamous “Form Four” recruiting contracts and significant sign-on fees.

It made Perth wingman Alan Johnson the Australian game’s first No.1 draftee – to Melbourne, where he played 135 games from 1982-1990 and won two club champion Keith Truscott Medals in 1983 and 1989 as a courageous, long-kicking midfielder. He also is a Melbourne Football Club Hall of Famer.

The first man picked in a (then) VFL draft, West Australian Alan Johnson (right), with former Melbourne teammate Brian Wilson.

Not so lucky was Footscray with the No.2 pick. It called Sturt midfielder Neil Craig, who never left the SANFL as a player.

This draft system lasted just two seasons (1981 and 1982) before it was revived in 1986 to cater for VFL expansion with Brisbane (that took Port Adelaide defender Martin Leslie at No.1) and West Coast (that had no picks until 1988 written into its entry conditions).

So even the so-called “first” edition of the current AFL national draft was compromised.

But nothing like the 2020 version to play out next week. NGA bids. Father-son picks. Free agency compensation picks. Special assistance package for Gold Coast. Northern academies.

During his hub stay in the Barossa Valley this season, Hawthorn premiership coach Alastair Clarkson clearly had much time to think about the state of the game – and just how different the rebuild options for his lowly Hawks are today when compared with first refit at the end of 2004.

That AFL national draft had three priority picks – including the second for Hawthorn that was used to claim Jarryd Roughead – and delivered the Hawks the jewels of Lance Franklin at No.5 and Jordan Lewis at No.7.

“It’s a bug bear of mine,” launched Clarkson of the compromises made to the AFL draft system – in particular the academy incentives handed to Brisbane, Gold Coast, Sydney and Greater Western Sydney to develop talent in the northern states (just as the VFL clubs enjoyed during the pre-AFL days with recruiting zones and junior and reserves teams).

In Queensland, noted Clarkson, “there’s two clubs (Brisbane and Gold Coast) that get the whole state in terms of access to junior talent.

“Sydney and GWS (Greater Western Sydney) share the whole of New South Wales in terms of any talent that comes through that state,” added Clarkson.

“When there’s that sort of compromise in what is meant to be an equal national competition, it makes it very, very difficult to find the talent necessary to give yourself a really good chance.

“Gold Coast has got access to parts of Northern Territory as well, so any significant Aboriginal talent like Cyril Rioli is going to come through the Gold Coast system. That is going to make it enormously difficult for a lot of clubs like North Melbourne and us to find our path back.

“It’s sounding like I am sooking about whether we can bounce (back) and we will, but it just makes it more difficult. People say, ‘Oh, why don’t you just rebuild. Just go to the draft’. You can’t go to the draft, it’s so compromised.”

More compromised than ever before.

The AFL next year will change the bidding system on NGA prospects. No matching bid – as is expected with Ugle-Hagan at No.1 – will be allowed in the first 20 draft picks in 2021; and first 40 picks in 2022.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Reverting to an uncompromised AFL draft would challenge many league agendas. None would be more sensitive than the “romance of Australian football” – the father-son concept developed 70 years ago to allow Ron Barassi to follow his late father’s footsteps to Melbourne. It has had at least 12 variations since the Barassi ruling in 1949.

Very few would tolerate the father-son rule being abolished to set up a pure, uncompromised draft. But even this concept of letting a son hang up his bag in his father’s old locker is vexed with inconsistent eligibility criteria – and difficulties for the “son of the gun”.

Sometimes, as the late Shane Tuck felt at Hawthorn where his father Michael had a larger-than-life figure on the club walls, it is best for the son to create his own name elsewhere (at Richmond in Tuck’s case).

Hawthorn first ignored the father-son option with Shane Tuck during the 1999 AFL national draft – just as Adelaide has done this time with Luke Edwards, the second son of club premiership hero and 321-game star Tyson Edwards.

After taking Jackson Edwards as a rookie in 2018 and delisting him without an AFL game to his name a year later, Adelaide’s call on Luke always carried that challenge of balancing recruiting needs in a testing rebuild for the Crows and the feel-good moment of seeing a son carry on the family story as a second-generation player in the Adelaide tri-colours.

“Obviously, it was a little bit disappointing to not follow in my dad’s footsteps,” says Edwards of being denied a father-son path to the No.9 locker at the Adelaide Football Club.

“Growing up, I always wanted to play for the Crows – just as much Dad and uncle Darren (Jarman) both played for the Crows. I would have loved to have played for them, but …

“Hopefully, there is an opportunity somewhere else because I want to get drafted,” added Edwards who is seen as a potential pick in the 30s range during the AFL national draft on December 9.

“I don’t really care where I go; I just want to play AFL to fulfill my dream.

“I probably would have (nominated as a father-son) just to stay home and to stay with the family, but I am happy to go anywhere to play footy. I was disappointed (to be overlooked by the Crows) but that is footy for you. I move on and hope I am lucky enough to be chosen.”

Father-son picks generally have been simple with the traditional Victorian-based clubs, as noted with Dustin Fletcher following his father Ken to Essendon in 1992; Luke Darcy in David’s footsteps at the Western Bulldogs in the same year, while Matthew Richardson stepped into his father Alan’s old locker room at Punt Road with Richmond.

And everyone points to the significant and extensive father-son gains at Geelong – Gary and Nathan Ablett, Matthew Scarlett, David Clarke, Tim Callan, Mark Blake, Tom Hawkins, Adam Donohue, Jed Bews, Sam Simpson, Oscar Brownless … and Simon Fletcher in 1995 based on his father Garry’s service as an administrator.

Meanwhile, St Kilda became envious of this generational dynasty while its club legends were blessed with daughters rather than sons – a theme that might now create depth for the Saints’ AFLW ambitions.

In South Australia, meanwhile, the angst with the varying father-son qualification systems and rulings has fuelled talkback radio shows since the lead-up to the 2006 AFL national draft.

The Crows thought they would be simply handing up a second-round draft pick for Bryce Gibbs – until the AFL ruled his father, former Glenelg player Ross, fell short of the 200 SANFL games in a 20-year qualification window between 1970 and 1990. Amid the outrage, Gibbs went to Carlton as the No.1 draftee.

Adelaide couldn’t pick up Bryce Gibbs under the father-son rule, father Ross ruled to have fallen short of 200 SANFL games.

More bizarre was Port Adelaide’s first AFL father-son pick, 2003 Magarey Medallist Brett Ebert who joined the Power in the 2002 national draft for pick No.42.

A forensic review of his father Russell’s record – 392 games from 1968-1985 with 25 at North Melbourne in 1979 – would have highlighted the SANFL has a different method to the VFL-AFL of counting senior games (to include Cup matches) – and, as with Ross Gibbs at Glenelg, would have fallen short of the 200 qualification matches during the 1976-1996 qualification period because of the absence in 1979 at North Melbourne.

The AFL excused the error saying it would be wrong if a son of Russell Ebert could not qualify for the father-son route to the big league.

Brett’s cousin Brad was not so lucky despite having paternal (Ebert) and maternal (Obst) relatives ranging from grandfathers, great uncles, uncles, cousins and his father Craig play for Port Adelaide in the SANFL.

Brad had to go to West Coast as pick No.13 in the 2007 AFL national draft and serve four seasons as an Eagle before being traded to his family club at Port Adelaide in 2011.

Adelaide’s long-awaited first father-son pick finally emerged in 2016 with the rookie listing of Ben Jarman. But there was no AFL moment for Jarman, who was delisted at the same time as Jackson Edwards after the 2018 AFL season.

The Crows still are waiting for their father-son story to become a reality … as will Gold Coast and Greater Western Sydney. Who argues the case for the Suns and Giants?

Port Adelaide last year called up Jackson Mead, son of inaugural AFL club champion Darren; and rookie listed Trent Burgoyne, son of 2004 AFL premiership hero Peter. It has another son of a 2004 premiership winner, Taj Schofield – son of wingman and current assistant coach Jarrad Schofield – in the draft mix too.

West Coast gained its first father-son in 1989 with defender Ashley McIntosh, based on his father John’s 146 WAFL games at Claremont – and Brownlow Medallist Ben Cousins in 1995 after his path to the AFL could have been with the Eagles, Geelong (where his father played 67 VFL matches along with his 238 WAFL senior games with Perth) and the newly-formed Fremantle.

The Dockers had their first father-son call in 2003 with Brett Peake, son of Brian who played 305 WAFL senior games with East Fremantle from 1972-1990, with this stretch interrupted from 1981-84 for 66 VFL games at Geelong where he arrived mid-season in 1981 – by helicopter.

In 2015 – when the AFL was under pressure to demand clubs potentially “pay” more than a second- or third-round draft pick for a father-son prospect – Sydney premiership coach Paul Roos (then at Melbourne) warned the league’s push to address the comprising nature of father-son picks on the integrity of the draft was setting up the moment noted with Luke Edwards today.

“They are more discouraging father-sons,” said Roos arguing for free passage on to an AFL list for a son rather than the current bidding system.

Jobe Watson followed his father Tim to Essendon with the Bombers giving up a third-round pick in the 2002 national draft. He regards the father-son theme in Australian football as “a great part of our game – and I know it means a lot to me.”

“And it’s great for the fans; it’s a really special and unique element of our game,” Watson says.

So is having AFL clubs involved in community football with the incentive of keeping a young star in the making rather than losing a development success story to a rival team during the national draft. In fact, getting AFL clubs more involved with grassroots football should be encouraged.

As Clarkson notes with the Queensland and New South Wales academies, all these extra agenda items do compromise the draft. But getting back to the original theme for the draft – last picking first in an open field – is highly unlikely, more so if the debate centres on the merit of the “traditional” father-son rule.