Convict artist Thomas Bock’s two sketches of Alexander Pearce after his execution by hanging.

Two hundred years ago today, a crowd of convicts were forced to watch as the so-called cannibal convict Alexander Pearce was hanged in the Hobart Town Gaol. Before his body was taken for dissection, convict artist Thomas Bock was ushered into the room where his corpse lay. Bock’s two sketches are the only known images of Pearce.

Pearce’s case was a sensation, and not just in the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land – by the middle of the 19th century, his skull would be in the possession of the University of Philadelphia. By then the Victorian Age, with its ideal of “Progress” being moral as well as social, was well underway. The story of Alexander Pearce, combined with the widespread belief that sodomy (otherwise termed “the unnatural vice”) was endemic among the penal colony’s male convict population, helped Van Diemen’s Land acquire its reputation as a dark place where, far from being a laboratory for the Victorian ideal of social and moral Progress, humans devolved, went backwards, regressed…

Victoria called itself Victoria precisely to make the point that it was not a Georgian hell-hole like Van Diemen’s Land or New South Wales, that it was part of the New Age then dawning in Britain under young Queen Victoria. Nearly 50 years after Pearce was hanged, a young Englishman working in the Melbourne Public Library, Marcus Clarke, sensationalised Pearce’s story in his book “For The Term of His Natural Life”.

One difference between the real story is that Clarke has the convicts escape from Port Arthur, in the more climactically benign south-east, and not Sarah Island, on the wild west coast. By the 1870s, Port Arthur had by then replaced Sarah Island as the island’s horror destination in the public imagination.

Another difference is that the cannibal who survives in the book is not at all like Pearce. He’s like a giant from a fairy tale. His name is Gabbet, he’s a flogger who grins as he goes about his awful work of cutting other men’s backs to pieces. There is arguably a Pearce character – an evil dwarf – but Gabbet kills and eats him. In 1927, the book was made into a highly successful silent movie which traded heavily on the pathos of the story. After that, Gabbet was a monster in the minds of millions.

Tasmanians associate the Pieman River on the west coast with Alexander Pearce but he never saw the river. Nor was he a Pieman. It was just that his story got mixed with that of Sweeney Todd, the London barber who murdered customers and used their remains as meat in his pies. Stories are like rivers – they can meet and merge.

Sarah Island was established in 1821 as “the Ultra Place of Banishment and Punishment”. The cat of nine tails employed there was larger, heavier and cut more deeply. As a convict, you could be working in freezing water with chains around your feet which chafed your skin. The bosses were convict foremen. If they said you were lazy, it was 100 lashes. One lash per minute.

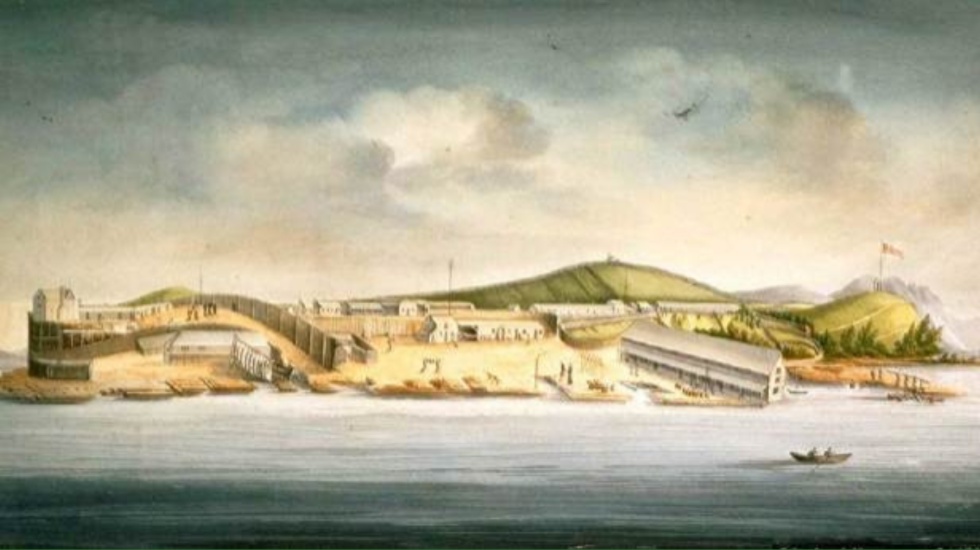

A sketch of Sarah Island in 1833 by Williams Buelow Gould.

There is a story of a man being flogged on Sarah Island, screaming for mercy after every lash. After the 30th, he went quiet. After the 35th, they realised he was dead. If another convict stole your shirt, you could get 50 lashes for losing an item of government property. Pearce said he escaped the second time because his shirt was stolen and he feared another flogging.

Basically, all we know about Pearce is contained in four statements he made after his two captures (he escaped twice). An Irishman aged about 30, he had been transported for stealing six pairs of shoes.

PLEASE HELP US CONTINUE TO THRIVE BY BECOMING AN OFFICIAL FOOTYOLOGY PATRON. JUST CLICK THIS LINK.

Pearce’s first escape is like the television show “Survivor” played with no food and one axe. Eight men head into the Tasmanian south-west – dense rainforest, mountainous terrain, wild rivers. Their clothes are torn off their backs, their shoes split and fall off. Their story is not without compassion – there are times when men diminish their chance of reaching the “settled areas” by waiting behind to assist companions. Eventually, however, it’s about survival and once the first fatal blow is struck and the principle of cannibalism accepted, a grisly game ensues.

When he’s captured after four months in the wilds, Pearce tells the authorities the truth. They think he’s lying to cover for his mates who are still at large, give him 100 lashes and send him back to Sarah Island where he’s a celebrity. He’s The One Who Got Away. A young bloke named Cox is at him to go again. Then his shirt is stolen….

The second time Pearce escaped he went north, got to the King River and found Cox couldn’t swim. Their plan was to walk right around the coastline of the island, around the north-west tip then east to Port Dalrymple where they hoped to steal a boat. They had many rivers to cross. Pearce killed Cox with an axe and ate parts of him. The next day he swam the King River, reached the other shore whereupon, in his words, “my heart gave way”.

He lit a fire, thereby signalling his whereabouts to his pursuers knowing full well he would be taken and hanged. The patrol that located him bound his hands, then searched his pockets and found what was described as “half a pound of meat”. What’s that, Pearce was asked. “Cox,” he replied. What really freaked out polite society in Hobart Town was that, in his other pocket, he was found to have bread crusts and scraps of pork – he had eaten human flesh by preference!

Sentencing him to death, the Chief Justice of Van Diemen’s Land appeared “much affected’ and said the case was “too inhuman” to comment upon. At which point, if I were writing a script, I would have Pearce say: I am what your system has made me.

Pearce mentioned in passing that during his first escape he contemplated suicide by hanging himself from a tree with his belt. The moment on his second escape when he lights the fire on the north bank of the King River, fully knowing the grotesque death that awaits him, is existential drama of a high order. At what point does a human being say – this is Hell. I’m leaving.

I have written this that he might be remembered not as a name but as a man.

I read this piece on Pearce with considerable interest.

Here’s my take on the man, in a short poem first published in The Adelaide Review way back in 1994, and after that in my first poetry collection, Vigorous Vernacular (Picaro Press, 2008; reprinted by Ginninderra Press, 2018).

The Ballad of Alexander Pearce

Back in Van Diemen’s Land,

in the good old days,

there was a handsome Irish criminal

named Alexander Pearce.

Apparently, he used to persuade

young convicts to escape with him

solely so he could eat them.

There is no potential for a folk song here.

Kevin Densley