Eddie McGuire speaks with the media after announcing his resignation on Tuesday. Photo: AFL MEDIA.

“This is an historic and proud day for the Collingwood Football Club.”

– Eddie McGuire, following the leaking of the ‘Do Better’ report on racism at Collingwood, February 1 2021.

“I got it wrong. I said it was a proud day and I shouldn’t have.”

– McGuire, addressing Collingwood members the following say, February 2 2021.

“People have latched on to my opening line last week and as a result I … have placed the club in a position where it is hard to move forward with the implementation of our plans in clear air.”

– McGuire, announcing his resignation as Collingwood president, February 9 2021.

Arguably the most powerful man in football is out as president of one of its biggest clubs, brought down by racism in the game, an issue the AFL – up until very recently in the game’s history – considered peripheral, and unworthy of much attention.

Eddie McGuire’s off-a-cliff fall from football powerbroker to spectator came following pressure to stand down immediately following the disastrous media conference that accompanied the release of the “Do Better” report into racism at the club.

McGuire had called the report’s release (actually, it was leaked) a “proud day”, but later told Collingwood’s annual general meeting he had “got it wrong”.

At the time, McGuire indicated he would not step down. But his position became untenable on Monday night when Indigenous community leaders, politicians and former Bomber Nathan Lovett-Murray called on him to step down.

In a very real sense, McGuire’s quick fire demise sums up the quandary facing football as clubs and the AFL fumble around in search of solutions to racism, which – despite its being a part of the game since Doug Nicholls patrolled the wing for Fitzroy – they’re just not geared to handle.

The first quote, from the day after the ‘Do Better’ report was leaked to the media, reflects a desire in many quarters to be “seen to be doing something” and to spin that ‘something’ as a positive.

The second came after the embarrassing revelation that at least some in the football world aren’t buying the spin, and want to see the actual change this report advocates.

The third is a warning to football administrators that those impatient with the pace of change have more pull than they reckoned with, and that, henceforth, riding out the news cycle isn’t necessarily going to cut it.

Racism has been a fact of football life since the early 1900s. The following is a chronological look at how football officialdom has dealt with this vexing issue over time, largely sweeping it under the carpet for almost a century before Nicky Winmar, one fateful Abbotsford afternoon, turned it into an issue they could no longer ignore. At that moment, racism in football went from the unmentionable to the unsolvable, a bane for administrators accustomed to selling conflict as entertainment, not tamping down a distasteful chunk of said conflict because someone moved the goalposts of acceptability at half time.

Those officials would never admit it, but many would have preferred it if Winmar hadn’t ventured across the Nullarbor to Moorabbin. Life was so much simpler for them before he did.

Race in football was such a taboo last century, even Indigenous players played it down. The first Indigenous player in the VFL, Joe Johnson of Fitzroy (55 games, 1904-06) never openly identified himself as an Aboriginal footballer (in later decades, several others also kept it to themselves).

Newspaper reports at the time said nothing about the racial and cultural identity of Johnson as an Aboriginal man, leaving his place in history tragically unacknowledged until after his death in 1934.

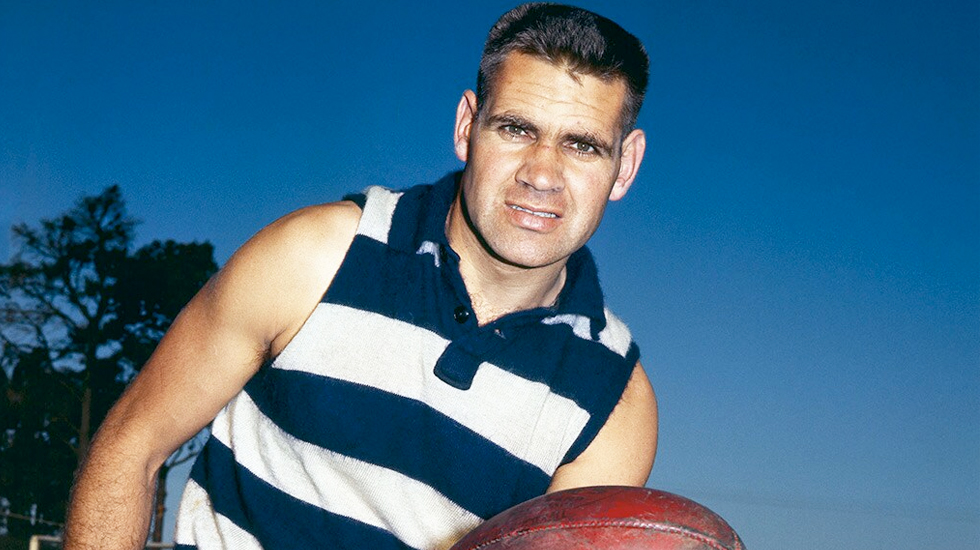

In later decades, talented indigenous players like Norm McDonald (Essendon) and Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer (Geelong) rarely made an issue of their ordeals, adopting a “stiff upper lip” philosophy. Neither openly reacted to racism from opponents or let fans bother them, with Farmer telling author Sean Gorman: “It was them that had a problem, not me”.

Champion Geelong Polly Farmer helped revolutionise the game. PHOTO: AFL Media.

“In those days … there was only two ways to lower the ability of opposing players … either slander them or physically assault them,” Farmer said in 1999.

“In my case I didn’t have a problem with that because all I did when I heard it, I came back just as strong”.

Farmer, in particular, had generational talents that – in an ideal world – could have transcended race, but elected not to make it an issue. Such was the culture of the time: racism and racial inequality were taboo.

Discrimination at club and league level went equally unacknowledged.

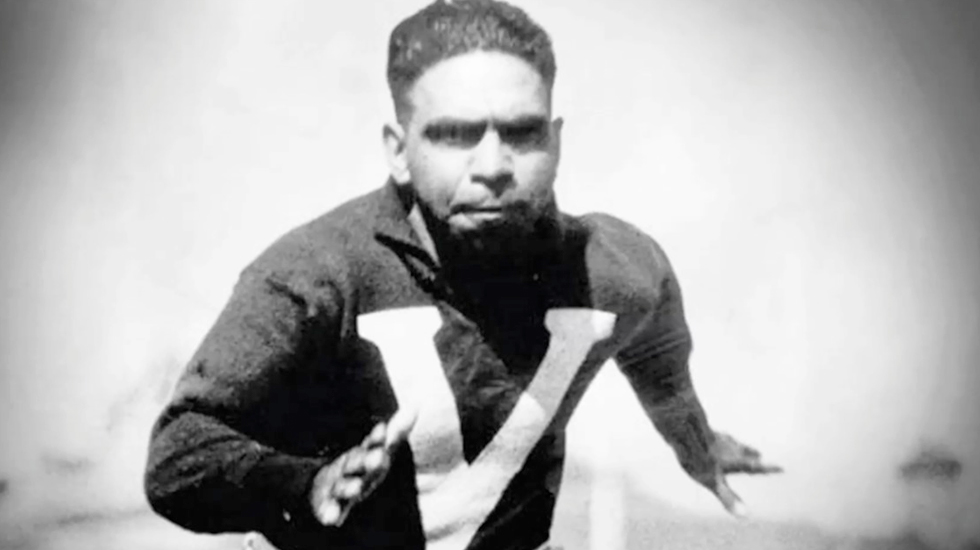

Doug Nicholls achieved great heights as minister and activist, and later as Sir Douglas Nicholls, Governor of South Australia, but not before discrimination at Carlton nearly cost him a VFL career.

“His teammates were not eager to play with an Aborigine. No one would willingly give him a rubdown. There were complaints that, because of his colour, he smelt”, wrote Mavis Thorp Clark in the biography “Pastor Doug”.

After a stint at Northcote, Nicholls joined Fitzroy, where he spent six seasons but remained on the outer with teammates for much of that time.

“He was in the rooms on his own. That feeling must have come across him again, that I’m not going to be accepted here,” his daughter Pam recalled.

The great Sir Doug Nicholls is pictured during his playing career. PHOTO: AFL Media.

Fitzroy legend Haydn Bunton Senior saw that Nicholls was feeling excluded and befriended him, but there was little support at club level in the face of ongoing ostracisation from some team mates, and torrents of abuse from opposition opponents and fans.

Nicholls struggled to amass 54 games in six seasons in the 1930s, ostensibly because of his short stature (5 ft 2 inches) but one is left to wonder how selectors would have treated a short but highly skilled wingman of Anglo Saxon extraction. None of this was seen as an issue at club and VFL level; unacknowledged by victim and perpetrator alike during an era when indigenous players were a small minority and wider society wouldn’t even acknowledge them as citizens.

By the 1970s and 80s, overt discrimination against Indigenous players at the selection table and in the changerooms had eased, but racial abuse from opponents and fans was as bad as ever. Adding fuel to the fire was the occasional refusal by some indigenous players to cop it.

By his third VFL season (1984) North Melbourne’s Jim Krakouer had emerged as an on-field enforcer who wouldn’t back down from racial abuse. Jim was reported three times that year, recalling in typically understated fashion that “something may have been said”. He complained to club secretary Ron Joseph, who could do little more than offer words of support. “The VFL’s constitution didn’t cater for racism”, wrote Matt Watson.

Even less inclined to wear the abuse was Robert Muir (St Kilda) who missed 22 VFL games due to suspensions, often the retaliator in incidents where opponents used racism as gamesmanship. Muir was labelled as “volatile” or “fiery” and given the nickname “mad dog” (code for something else?) by journalists and fellow players who focused more on the violence than the reasons behind it. Those reasons were plentiful.

“He endured nothing but hounding and harassment — a decade-long chronicle of racial abuse and mistreatment, including incidents in which he was spat at, urinated on, pelted with bottles and set upon by mobs of racist fans”, wrote Russell Jackson.

Unlike many before him, Muir wasn’t one to grin and bear it, but the only weapon at his disposal in a game that refused to acknowledge its race problem was his fists. Ultimately, Muir was hounded out of the VFL, suspended for 12 weeks after deciding he “wasn’t going to take” the abuse one especially spiteful afternoon at Carlton in 1984.

Football’s faltering attempts to address racial issues in recent years led, in some cases, to severely belated apologies. In 2016, Carlton finally acknowledged – almost 90 years after the fact – that it had racially vilified Doug Nicholls.

“He was excluded … due to his Aboriginality,” CEO Steven Trigg said. “It’s worth thinking for a moment about how those actions must have made him feel.”

Robert Muir, for his part, received an unreserved apology from both the club and the AFL for “the disgraceful racism and disrespect [he] endured during his playing years in our game”.

“Unfortunately there are too many stories like [Muir’s] in our code and country’s history,” the AFL continued, and they’re right. The stories of Doug Nicholls and Robert Muir are among a minority of cases that received publicity, with Muir’s apology coming the day after Russell Jackson’s investigation was reported by the ABC.

Some 50 Indigenous players debuted at VFL level from 1904 through the 1980s, every one of them on the wrong end of abuse and in some cases, active discrimination. Every one of them is entitled to an apology, even posthumously. In many instances, none has been forthcoming.

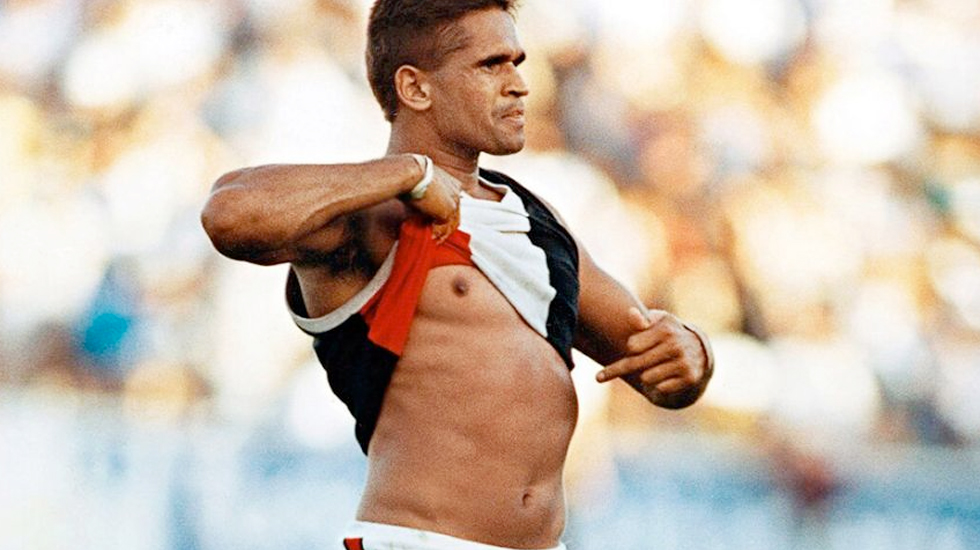

Nicky Winmar’s seemingly off-the-cuff gesture at Victoria Park in 1993 was a catalyst for the change which ultimately led to McGuire’s Tuesday resignation. Codes of conduct were changed, mediations introduced, and reports written, at AFL and club level.

People forget that words have a big impact. They can lift a person or destroy a person. So that day I responded by saying to those people, and I still say it today: ‘I’m black and I’m proud’,” Winmar later said.

Nicky Winmar takes a stand against the racist cries from the Collingwood crowd in 1993. PHOTO: Wayne Ludbey.

Milestones on that 28-year road include:

* 1995: Collingwood’s Damian Monkhorst alleged to have called Essendon’s Michael Long a “black bastard” during the Anzac Day clash that year. The ramifications from that incident still echo through the AFL today after racial vilification laws were brought in on the back of that one incident.

* 1999: St Kilda’s Peter Everitt racially abuses Melbourne’s Scott Chisholm during a game. Everitt is suspended for four games, donates $20,000 to a charity of Chisholm’s choice and undertakes a racial awareness training program.

* 2011: Western Bulldogs’ Justin Sherman racially vilifies Gold Coast’s Joel Wilkinson. Sherman is banned for four games, ordered to attend an education program and pay $5000 to a charity chosen by the Suns.

* 2012: The AFL’s national community engagement manager Jason Mifsud claims Adelaide’s recruitment manager Matthew Rendell suggested clubs may adopt a policy of only recruiting Aboriginal players with at least one white parent. Rendell apologises and resigns, saying his comments were taken out of context.

* 2013: Sydney’s Adam Goodes is called an ape by a 13-year-old Collingwood supporter during a game. Goodes points the girl out to security, saying he was distressed by the comment but adds: “People need to get around her. She’s 13, she’s uneducated.”

* 2014: A 70-year-old spectator is reported to police for making racists comments to Sydney Swans Lance Franklin and Goodes during a match against Western Bulldogs at Etihad Stadium.

* 2014: North Melbourne’s Majak Daw is racially abused by a spectator during a match against Hawthorn in Launceston. The male spectator is evicted from the ground.

* 2014: West Coast’s Nic Naitanui is racially abused on Twitter. The offender pleads guilty to three counts of using a carriage service to menace, harass or cause offence and is banned from creating a Twitter account.

* 2015: Sydney’s Goodes is hounded out of the game by spectators. Believing the jeering to be racist, Goodes steps down from playing but returns after widespread support. He retires at the end of the season.

* 2016: A banana is thrown at Adelaide’s Eddie Betts by a female Port Adelaide supporter during a game. “A banana being thrown at an Indigenous man is unambiguously racist,” AFL chief Gillon McLachlan says. Port suspend the woman’s club membership indefinitely.

* 2017: Adelaide’s Eddie Betts is racially abused by a Port fan during a game, and by another Port supporter on social media. Port’s Paddy Ryder is also racially vilified by a Crows supporter during the same game.

* 2021: The ‘Do Better’ report on racism at Collingwood is leaked to the media. Initially lauding the report’s release as a “proud day” for the club, president Eddie McGuire is quickly forced to admit he had “got it wrong” before an unprecedented outcry forces his resignation on February 9.

Notwithstanding a disappointing reaction from the outer in the case of Goodes and others, the above timeline represents progress on the issue of racism, with some high-profile casualties along the way. Racial vilification penalties have led to a precipitous decline in on-field abuse. Clubs continue to wrestle with race within their administrative ranks (such as Collingwood) but they’re talking about it, and no doubt feel some obligation to change following McGuire’s demise, something that would have seemed a pipe dream just a few years ago.

Perhaps the last frontier for football lies in changing the attitudes of its fan base, something that is arguably outside the AFL’s purview. The league’s crackdown on loud and abusive spectators in 2019 seemed to open a can of worms, with security guards policing crowd behaviour and one Carlton fan ejected from Marvel Stadium for calling umpire Mathew Nicholls a “bald-headed flog”. Hardly racism, and that poses a critical question: where do you draw the line?

Fortunately, the AFL’s ‘thought police’ was a short-lived experiment, as the burden of educating people on race and other niceties fell back to our schools and homes. That said, racism on the terraces is an ongoing dilemma for football, with no immediate solution in sight.

Nonetheless, Eddie McGuire’s demise as Collingwood president shows an impetus for change on racism that goes beyond the spin and glossy brochures ritually employed by officialdom the world over to “be seen to be dealing with” a problem they’re not totally committed to ending.

Changing one’s entrenched attitudes is challenging and uncomfortable, and when officials with the power to resist are the ones being challenged, achieving change is that much harder.

In spite of this, arguably the biggest name in football has been brought down. Let’s hope that’s something meaningful, and not just another boardroom coup.